One of the core barriers to economic prosperity in California is the price of housing. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Policies designed to stifle the ability to develop land are based on flawed premises. These policies prevail because they are backed by environmentalists, and, most importantly, because they have played into the agenda of crony capitalists, Wall Street financiers, and public sector unions. But while the elites have benefit, ordinary working families have been condemned to pay extreme prices in mortgages, property taxes, or rents, to live in confined, unhealthy, ultra high-density neighborhoods. It is reminiscent of apartheid South Africa, but instead of racial superiority as the supposed moral justification, environmentalism is the religion of the day. The result is identical.

Earlier this month an economist writing for the American Enterprise Institute, Mark J. Perry, published a chart proving that over the past four years, more new homes were built in one city, Houston Texas, than in the entire state of California. We republished Perry’s article earlier this week, “California vs. Texas in one chart.” The population of greater Houston is 6.3 million people. The population of California is 38.4 million people. California, with six times as many people as Houston, built fewer homes.

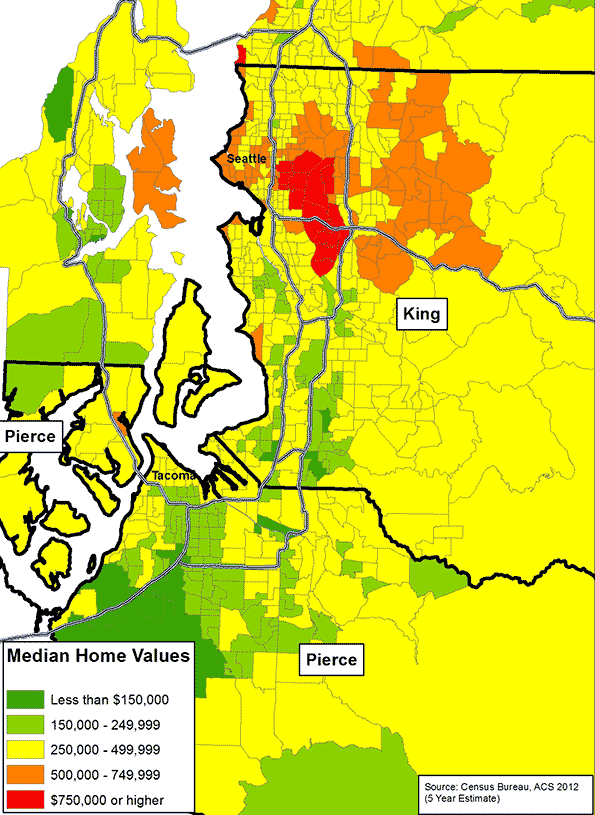

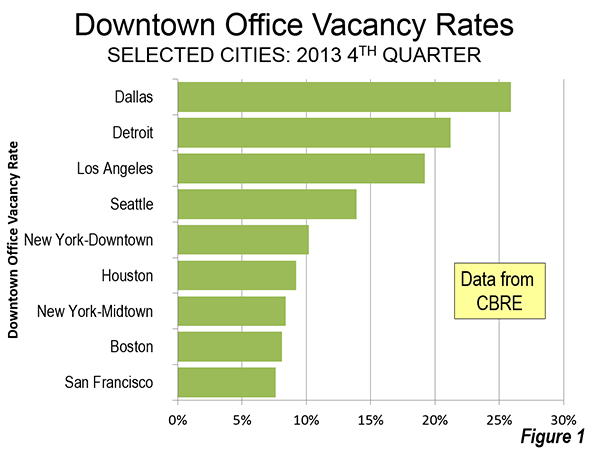

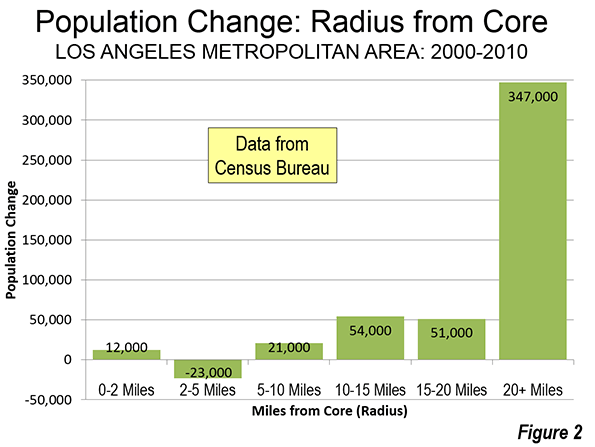

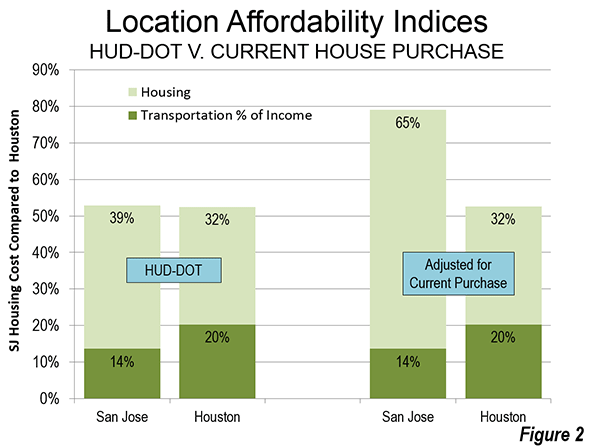

And when there’s a shortage, prices rise. The median home price in Houston is $184,000. The median price of a home in Los Angeles is $530,000, nearly three times as much as a home in Houston. The median price of a home in San Francisco is $843,000, nearly five times as much as home in Houston. What is the reason for this? There may be a shortage of homes, but there is no shortage of land in California, a state of 163,000 square miles containing vast expanses of open space. What happened?

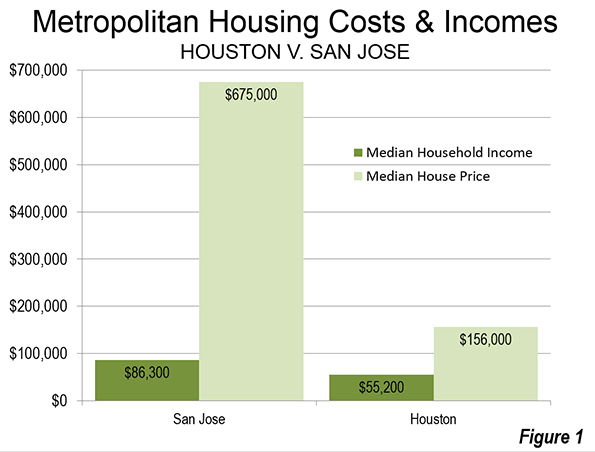

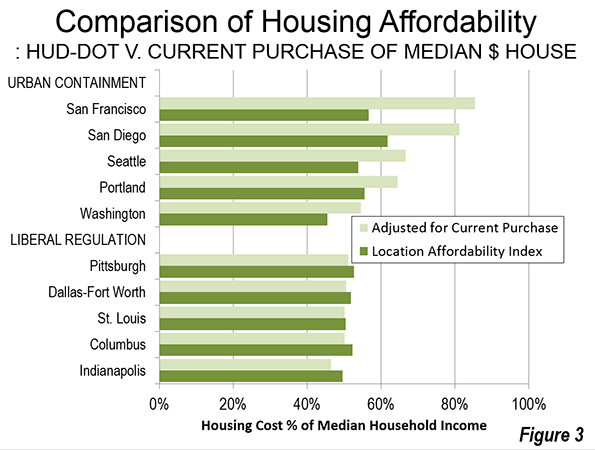

You can argue that San Francisco and Los Angeles are hemmed in by ocean and mountains, respectively, but that really doesn’t answer the question. In most cases, these cities can expand along endless freeway corridors to the north, south, and east, if not west, and new urban centers can arise along these corridors to attract jobs. But they don’t, and the reason for this are the so-called “smart growth” policies. In an interesting report entitled “America’s Emerging Housing Crisis,” Joel Kotkin calls this policy “urban containment.” And along with urban containment, comes downsizing. From another critic of smart growth/urban containment, economist Thomas Sowell, here’s a description of what downsizing means in the San Francisco Bay Area suburb Palo Alto:

“The house is for sale at $1,498,000. It is a 1,010 square foot bungalow with two bedrooms, one bath and a garage. Although the announcement does not mention it, this bungalow is located near a commuter railroad line, with trains passing regularly throughout the day. The second house has 1,200 square feet and was listed for $1.3 million. Intense competition for the house drove the sale price to $1.7 million. The third, with 1,292 square feet (120 square meters) and built in 1895 is on the market for $2.3 million.”

And as Sowell points out, there are vast rolling foothills immediately west of Palo Alto that are completely empty – the beneficiaries of urban containment.

The reason for all of this ostensibly is to preserve open space. This is a worthy goal when kept in perspective. But in California, NO open space is considered immediately acceptable for development. There are hundreds of square miles of rolling foothills on the east slopes of the Mt. Hamilton range that are virtually empty. With reasonable freeway improvements, residents there could commute to points throughout the Silicon Valley in 30-60 minutes. But entrepreneurs have spent millions of dollars and decades of efforts to develop this land, and there is always a reason their projects are held up.

The misanthropic cruelty of these polices can be illustrated by the following two photographs. The first one is from Soweto, a notorious shantytown that was once one of the most chilling warehouses for human beings in the world, during the era of apartheid in South Africa. The second one is from a suburb in North Sacramento. The scale is identical. Needless to say, the quality of the homes in Sacramento is better, but isn’t it telling that the environmentally enlightened planners in this California city didn’t think a homeowner needed any more dirt to call their own than the Afrikaners deigned to allocate to the oppressed blacks of South Africa?

The Racist Bantustan

Soweto, South Africa – 40′ x 80′ lots, single family dwellings

When you view these two studies in urban containment, consider what a person who wants to install a toilet, or add a window, or remodel their kitchen may have to go through, today in South Africa, vs. today in Sacramento. Rest assured the ability to improve one’s circumstances in Soweto would be a lot easier than in Sacramento. In Sacramento, just acquiring the permits would probably cost more time and money than doing the entire job in Soweto. And the price of these lovely, environmentally correct, smart-growth havens in Sacramento? According to Zillow, they are currently selling for right around $250,000, more than five times the median household income in that city.

The Environmentalist Bantustan

Sacramento, California – 40′ x 80′ lots, single family dwellings

When you increase supply you lower prices, and homes are no exception. The idea that there isn’t enough land in California to develop abundant and competitively priced housing is preposterous. According to the American Farmland Trust, of California’s 163,000 square miles, there are 25,000 square miles of grazing land and 42,000 square miles of agricultural land; of that, 14,000 square miles are prime agricultural land. Think about this. You could put 10 million new residents into homes, four per household, on half-acre lots, and you would only consume 1,953 square miles. If you built those homes on the best prime agricultural land California’s got, you would only use up 14% of it. If you scattered those homes among all of California’s farmland and grazing land – which is far more likely – you would only use up 3% of it. Three percent loss of agricultural land, to allow ten million people to live on half-acre lots!

And what of these lots in North Sacramento? What of these homes that cost a quarter-million each, five times the median household income? They sit thirteen per acre. Not even enough room in the yard for a trampoline.

There is a reason to belabor these points, this simple algebra. Because the notion that we have to engage in urban containment is a cruel, entirely unfounded, self-serving lie. You may examine this question of development in any context you wish, and the lie remains intact. If there is an energy shortage, then develop California’s shale reserves. If fracking shale is unacceptable, then drill for natural gas in the Santa Barbara channel. If all fossil fuel is unacceptable, then build nuclear power stations in the geologically stable areas in California’s interior. If there is a water shortage, than build high dams. If high dams are forbidden, then develop aquifer storage to collect runoff. Or desalinate seawater off the Southern California coast. Or recycle sewage. Or let rice farmers sell their allotments. There are answers to every question.

Environmentalists generate an avalanche of studies, however, that in effect demonize all development, everywhere. The values of environmentalism are important, but if it weren’t for the trillions to be made by trial lawyers, academic careerists, government bureaucrats and their union patrons, crony green capitalist oligarchs, and government pension fund managers and their partners in the hedge funds whose portfolio asset appreciation depends on artificially elevated prices, environmentalism would be reined in. If it weren’t for opportunists following this trillion dollar opportunity, environmentalist values would be kept in their proper perspective.

The Californians who are hurt by urban containment are not the wealthy elites who find it comforting to believe and lucrative to propagate the enabling big lie. The victims are the underprivileged, the immigrants, the minority communities, retirees who collect Social Security, low wage earners and the disappearing middle class. Anyone who aspires to improve their circumstances can move to Houston and buy a home with relative ease, but in California, they have to struggle for shelter, endlessly, needlessly – contained and allegedly environmentally correct.

Ed Ring is the executive director of the California Policy Center.