People care deeply about where they live. If you ever doubt that, remember this: they staged massive protests over a park in Istanbul. Gezi Park near Taksim Square is one of that ancient city’s most beloved spots. So in June, when Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan threatened to demolish the park to make room for his grandiose vision of the city as “the financial center of the world,” the park’s neighbors and supporters took to the streets. The protests were directed against what has been described as “authoritarian building”—the demolition of older, more-human-scaled neighborhoods in favor of denser high-rise construction, massive malls, and other iconic projects.

Other protests, usually more peaceful, but sparked by a similar revulsion against gigantism, have erupted in cities as various as Sao Paolo, Singapore, and Los Angeles. But what is most striking are the eerily similar reactions of mayors, city planners, architects, and developers, all of whom seem remarkably tone deaf to the wishes of their constituents.

New York’s Mayor Michael Bloomberg, for example, is a tireless advocate for more density in the Big Apple. Along with many of the world’s leading academic, media, and real estate leaders, Bloomberg dreams of a future where urban dwellers live cheek by jowl in ever-closer proximity. Bloomberg’s notions are supported not only by developers but also a large cadre of academics, such as Columbia University’s Kenneth Jackson, who considers dissent from the mayor’s plans an affront to “Gotham’s towering ambitions” by reactionary “opponents of change.”

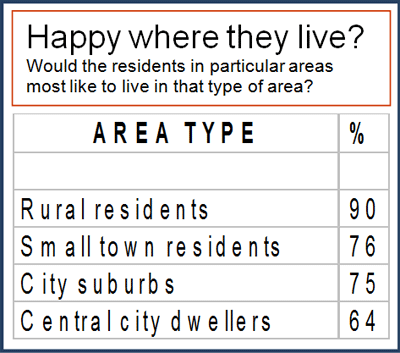

There’s just one problem with this brave new condensed world: most urban residents aren’t crazy about it. In the United States and elsewhere, people, when asked, generally say they prefer less dense, less congested places to live. The grandiose vision of high-rise, high-density cities manifestly does not respond to the actual needs and desires of most people, who continue to migrate to the usually less congested, and often less expensive, periphery. And as the people’s desires continue to run counter to what those in power dictate, the urban future is likely to become increasingly contentious.

Protests over urban development priorities similar to Istanbul’s occurred earlier this year in São Paulo, where the government is accused of putting mega-projects ahead of basic services such as public transport, education, and health care, particularly in the run-up to the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics.

Singapore, often held up as a role model for densification, has seen growing concern about the destruction of historic structures, ever-more crowded subways, escalating house prices, and lack of open space. Similarly in Los Angeles, neighborhood councils have rallied against attempts to build denser buildings, which generate more congestion and erode local character. In London, too, attempts to build what the Independent describes as “the tall, the ostentatious, the showy and ‘iconic’” have been widely criticized for undermining the human-scaled nature ofLondon. Densification may be revealed religion to British planners, but this faith is not well accepted by citizens who live nearby. Novelist Will Self noted the “Wizard of Oz–hollowness” of these structures that seek to inspire but also “belittle us” with the mass, scale, and stand against this great city’s historic grain.

Even in Manhattan, the red-hot center of American ultra-density, eight of the island’s 10 community boards oppose Mayor Bloomberg’s attempts to densify midtown. The midtown project has prompted Yale architect Robert Stern, a devoted urbanist and no opponent of density, to warn that too much high-rise development creates a dehumanized aesthetic that chases away creative businesses and tourists, while preserving older districts attracts them.

Voting With Their Feet

The growing disconnect between people and planners is illustrated by the oft-ignored fact that around the world the great majority of growth continues to occur on the suburban and exurban frontier, including the fringes of 23 out of 28 of the world’s megacities. This, notes NYU professor Shlomo Angel in his landmark book A Planet of Cities, is true both in developing and developed countries.

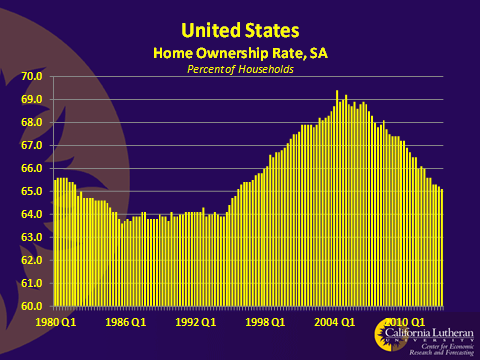

In Europe, immigration has slightly boosted populations in urban cores, but the flow of domestic migration still heads towards the periphery. The evidence is even more telling in the U.S. In the last decade, nearly 90 percent of all metropolitan growth in this country took place in suburban locations, up from the previous decade. At the same time, a net 3.5 million people left our largest metropolitan areas—those over 10 million—while the majority of growth took place in cities under 2.5 million. Between 2000 and 2010, a net 1.9 million left New York, 1.3 million left Los Angeles, 340,000 left San Francisco, and 230,000 left both San Jose and Boston.

This is not what you read regularly in the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal. Young reporters, virtually all of whom live in dense, expensive places like New York or Washington, believe the world is the one they know first-hand, the one in which they and their friends reside. Yet most Americans are not young, highly educated Manhattan residents. Many downtown areas may have experienced a substantial boost in numbers over the last decade, but this accounted for less than 1 percent of the 27 million in population growth experienced by the nation between 2000 and 2010. The total population increase in counties with under 500 people per square mile was more than 30 times that of the increase in counties with densities of 10,000 and greater.

All of this flies in the face of the argument, made by a well-funded density-boosting industry, that people want more density, not less. Lobbies to force people back into cities enjoy generous funding provided by urban land interests and powerfulmultinationals that build subways and other city infrastructure to bolster the cause of ever greater density.

These interests speak about cities as if they were giant Lego constructions to be toyed with at the whim of planners or developers. But they neglect the things that matter to people in their daily lives: privacy, room to raise children, the desire for a backyard, decent schools, and safe streets. Roughly four in five home buyers, according to a 2011 study conducted by the National Association of Realtors and Smart Growth America, for example, prefer a single-family home, something that is anathema to the densifiers.

The Political Economy of Density

In the Obama era, the cause of densification has gained strong support at HUD, EPA, and other agencies. Yet this is hardly an issue any sane politician—outside New York anyway—wants to run with. People pretty much everywhere naturally resist increasing densification and gigantism—and favor what the Taksim Squareprotesters call a drive for “healthy urbanization and livable city.”

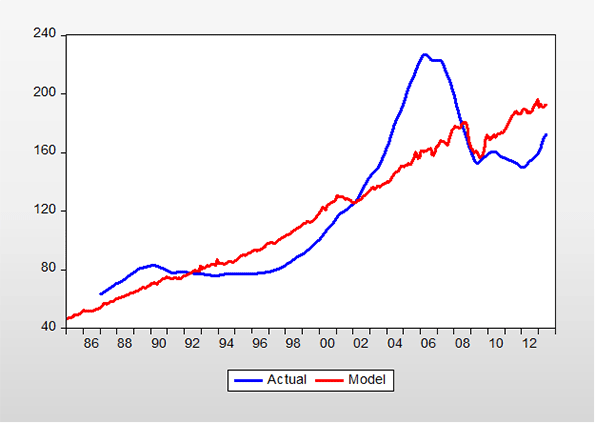

Densifiers also claim their work makes cities richer, yet the nation’s greatest wealth-creator—Silicon Valley—is essentially suburban, and the world’s wealthiest metropolitan area—greater Hartford, Connecticut—is largely a collection of bucolic towns and suburbs with a density nearly as low as Atlanta’s. In addition, nearly all urban cores, including New York and Chicago, have considerably higher unemployment rates than their much-dissed suburban rivals. Overall, notes demographer Wendell Cox, 80 percent of the last decade’s urban population growthcame from people below the poverty line, compared with one third in suburbs.

The new urban densification also shifts the role of the city from an aspirational model to what might be called the geography of inequality. Economists such as Ed Glaeser speak about density as an unalloyed factor in wealth creation, but they rarely factor in such things as cost of living, or in how such factors affect the middle and working classes.

Glaeser’s favorite city, New York, is also America’s most unequal metropolis, where the 1 percent earn roughly twice as much of the local GDP than is earned in the rest of country, and where the average paycheck, when controlled for costs, is among the lowest among the nation’s 51 largest metro areas, behind not only San Jose, but Houston, Raleigh, and a host of less celebrated burgs. These inequalities are precisely what opened the door for the previously obscure leftist Bill de Blasio to make his impressive mayoral run. And Gotham’s great rival, London, according to one recent study, now may be the most unequal major city in the Western world.

Yet rather than re-think density, planners and powerful urban land interests continue to force ever higher-density development down the throats of urban dwellers. In the already pricey San Francisco Bay Area, for example, municipal planners have embraced what is known as a “pack and stack” strategy that will essentially prohibit construction of all but the most expensive single-family homes, prompting one Bay Area blogger to charge that “suburb hating is anti-child,” because it seeks to undermine single-family neighborhoods.

Unsustainable Post-Familial Cities of Asia

Perhaps the key measurement of social sustainability is the willingness of people to have children. Historically we fear overpopulation, but increasingly, at least in high-income countries, the real challenges may be over rapid aging and a diminished workforce. There is a countries, the real issue is now below replacement birthrates and rapid aging. High-density environments such as Manhattan, San Francisco, Seattle, Washington, D.C., or Boston invariably have the lowest percentages of children in the country, with Japan-like fertility rates (by 2050 there may well be more Japanese over 80 than under 15).

The negative impacts of densification are even more evident in the fast-rising cities of the developing world, where most of new high-rise office and residential towers are being erected. In 1980 the world’s 10 tallest buildings were found in New York, Chicago, Houston, and Toronto. Today, only one building in North America—the Sears Tower in Chicago, built in 1973—ranks among the world’s tallest. The rest are located in Dubai, Mecca, Kuala Lumpur, Shenzen, Nanjing, Taipei, Hong Kong, and Shanghai, where the world’s second-tallest building is nearing completion.

These towers symbolize Asia’s economic ascendency, but they also seem to diminish grassroots economies and discourage family formation. The ultradense cities of East Asia—Hong Kong, Singapore, and Seoul—have among the lowest fertility rates on the planet. Tokyo and Seoul now have fertility rates around one child per family while Shanghai’s has fallen to 0.7, among the lowest ever reported, well below the “one child” mandate and barely one-third the number required simply to replace the current population. Due largely to crowding and high housing prices, 45 percent of couples in Hong Kong say they have given up having children.

Some Asian urban residents, if they can, now seek to leave these cities—among the most widely praised by urbanists—for more affordable and lower density locales. This is evident in rising emigration from China’s cities, Hong Kong, and Singapore, where roughly one in 10 citizens now chooses to settle abroad, mostly in lower density countries like Australia, Canada and the United States.

To some, this boils down to an issue of health. Dense urbanization, notes a recent Chinese study, engenders more obesity, particularly among the young, who get less exercise, and spend more time desk-bound. Stroke and heart disease have become leading causes of death. These concerns have led, even in authoritarian China, to growing grassroots protests, many of them targeted at new industrial plants located near cities, including Shanghai.

Perhaps no developing city better reflects the brutalism of Asia’s emerging urban paradigm than Seoul, the densest of the high-income world’s urban areas over 10 million (megacities). The Korean capital is more than 2.5 times as crowded as Tokyo, twice as dense as London and five times as crowded as New York. No surprise then that urban pundits love the place, as epitomized by a glowing report in Smithsonianon Seoul as “the city of the future.” Architects, naturally, join the chorus. In 2010, the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design named the Seoul the “world design capital.”

Rarely considered, however, is whether this form of urbanization creates a good place for people, particularly families. Korea is already among the unhappiest places on earth, according to a recent study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and, not surprisingly, suffers a birthrate even lower than Singapore’s.

Seoul is, as its boosters claim, fully modern but also both highly congested and aesthetically barren. The result, notes one recent Korean newspaper article is one of the most dehumanized and aesthetically unappealing cities on the planet. MIT architecture professor Lee Kwanghyun charges that over the past decade, development has effectively replaced Seoul’s once unique neighborhoods with seemingly endless blocks of 200-foot high white concrete boxes.

Public opposition to this approach has been mounting, and Seoul’s city government recently suspended a “new towns” proposal that sought to knock down the city’s last remaining low-density areas. Not surprisingly, Koreans have been rejecting the hyper-dense core of Seoul, which has lost nearly 1 million residents (10 percent) in 20 years, with residents and migrants from elsewhere in the country heading for the relatively less dense suburbs.

The City of Disappointment

The damage done to people by megacity urbanism is most pronounced in poorer countries. My colleague Ali Modarres calls places like Tehran “cities of disappointment.” There, he notes, high housing prices and lack of space have already reduced the birthrate to well below the replacement level, a phenomena he also sees in such unlikely places as urban Tunis, Istanbul, and many otherdeveloping cities in the Islamic world. As in Asia, Modarres says, marriage rates are dropping and increasingly many women are choosing to remain single—heretofore something rare in these countries.

In cities like Tehran, Modarres says, housing has become equated with living in a small apartment/condominium in a residential building. Rarely does the younger population think about housing in terms of a detached single-story building. And the exorbitant cost of housing in such a high-density city in turn creates constant worries about money and housing—having even one child is prohibitively expensive.

Gigantism’s effects in the developing world—where much of the most rapid urban growth is now taking place—is even more profound. In Mumbai, home to 20 million people, life expectancy for city residents is at least 10 years below the life expectancy of their country cousins, even though urban residents have much better access to health care. And nearly four of five urban households complain about contaminated water. In 1971, slum dwellers accounted for one in six Mumbai residents. Today, they constitute an absolute majority.

Indeed, much of the population of most developing country cities—such as Mexico City, Cairo, Jakarta, Manila, Lagos, Mumbai, and Kolkata, megacities all—continue to live in “informal” housing that is often unhygienic, dangerous, and subject to all kinds of disasters, natural or man-made. Moreover, many of these unmanageable megacities—most notably Karachi—offer ideal conditions for gang-led rule and unceasing ethnic conflict.

Remarkably, many Western pundits find much to celebrate in megacities mushrooming in low-income countries. To them, the growth of megacities is justified because it offers something more than unremitting rural poverty. But surely there’s a better alternative than celebrating slums, as one prominent author did recently inForeign Policy.

In the mainstream press, there’s even a tendency to engage in what one critic has labeled “slumdog tourism.” A recent National Geographic article, for example, celebrated the entrepreneurial spirit of Kinshasa’s slum dwellers, which is understandable, but underplayed the miserable conditions in which the majority of Kinshasa’s eight million residents are forced to live. That city, which Belgian researchers described as an example of “aborted urban development,” suffers from high crime, poor drinking water, and pervasive informal housing. Similar conditions exist in virtually all of Africa’s largest cities, which are growing as fast as any in the world.

Toward a Human City

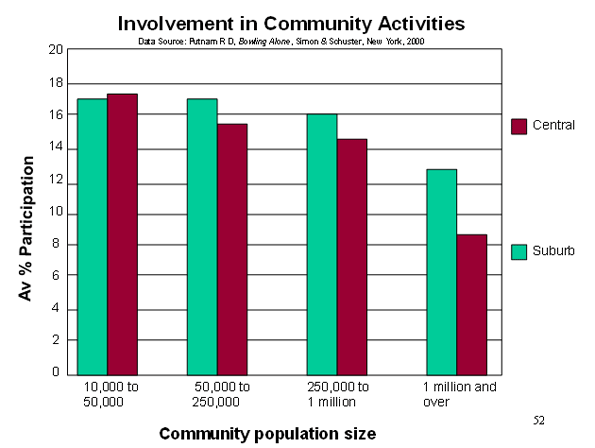

Rather than concocting sophisticated odes to misery, perhaps we might consider a different approach to urban growth. Perhaps we factor in what exactly we are inflicting on people with “pack and stack” strategies. Planners often link density with community, notes British social critic James Heartfield, but maintaining that “physical proximity that is essential to community is to confuse animal warmth with civilization.” When University of California at Irvine’s Jan Brueckner and Ann Largey conducted 15,000 interviews across the country, they found that for every 10 percent drop in population density, the likelihood of people talking to their neighbors once a week goes up 10 percent, regardless of race, income, education, marital status, or age. In 2009, Pew recently issued a report that found suburbanites to be the group far more engaged with their communities than those living in core cities.

A market—or simply human—approach would permit a natural shift towards smaller, less dense cities and, yes, the suburbs, where more people end up wanting to live. Those who prefer high-density living would still have their opportunity if they so desire. In the developing world, we might to find ways of making villages and smaller cities more attractive, perhaps through the development of local industries, farm-to-market agriculture, and even high-tech development. “We are copying the Western experience in our own stupid and silly way,” says Ashok R. Datar, chairman of the Mumbai Environmental Social Network. “For every tech geek, we have two to three servants. The villages pour out and the city gets more crowded.”

The primary goal of a city should not be to make wealthy landlords and construction companies ever richer, or politicians more powerful. Instead, we should look for alternatives that conform to human needs and desires, particularly those of families. Urbanism should not be defined by the egos of planners, architects, politicians, or the über-rich, who can cherry-pick the best locales in gigantic cities. Urbanism should be driven above all by what works best for the most people.

This story originally appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Skyline photo by Bigstock.