The current housing recovery may be like manna to homeowners, but it may do little to ease a growing shortage of affordable residences, and could even make it worse. After a recession-generated drought, household formation is on the rise, notes a recent study by the Harvard Joint Center on Housing Studies, and in many markets there isn’t an adequate supply of housing for the working and middle classes.

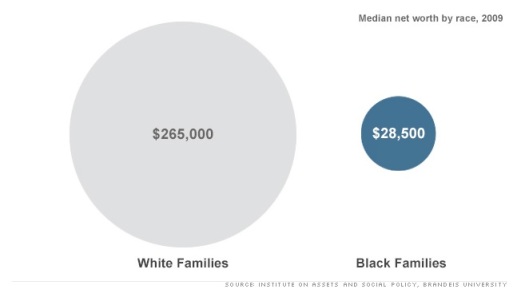

Given problems with regulations in some states, particularly restrictions on new single-family home development, the uptick in housing prices threatens both prospective owners and renters, forcing people who would otherwise buy into the rental market. Ownership levels continue to drop, most notably for minorities, particularly African Americans. Last year, according to the Harvard study, the number of renters in the U.S. rose by a million, accompanied by a net loss of 161,000 homeowners.

This is bad news not only for middle-income Americans but even more so for the poor and renters. The number of renters now paying upward of 50% of their income for housing has risen by 2.5 million since the recession and 6.7 million over the decade. Roughly one in four renters, notes Harvard, are now in this perilous situation. The number of poor renters is growing, but the supply of new affordable housing has dropped over the past year.

So while the housing recovery — and the prospect of higher prices — does offer some relief to existing homeowners, it’s having a negative impact further down the economic ladder. For the poorest Americans, nearly eight decades of extensive public subsidies have failed to solve their housing crisis. Given the financial straits of most American cities — particularly those like Detroit that need it the most — it’s unlikely the government can rescue households stressed by the cost of shelter.

As one might suspect, the problem is greatest in New York, New Jersey and California, say the Harvard researchers .In those three states 22% of households are paying more than 50% of pre-tax income for housing, while median home values and rents in these states are among the highest in the country. According to the Center for Housing Policy and National Housing Conference, 39% of working households in the Los Angeles metropolitan area spend more than half their income on housing, 35% in the San Francisco metro area and 31% in the New York area. All of these figures are much higher than the national rate of 24%, which itself is far from tolerable.

Other, poorer cities also suffer high rates of housing poverty not because they are so expensive but because their economies are bad. In the most distressed neighborhoods of Baltimore, Chicago, Cleveland and Detroit, where vacancy rates top 20%, about 60% of vacant units are held off market, indicating they are in poor condition and likely a source of blight.

America’s emerging housing crisis is creating widespread hardship. This can be seen in the rise of families doubling up. Moving to flee high costs has emerged as a major trend, particularly among working-class families. For those who remain behind, it’s also a return to the kind of overcrowding we associate with early 20th century tenement living.

As was the case then, overcrowded conditions create poor outcomes for neighborhoods and, most particularly, for children. Overcrowding has been associated with negative consequences in multiple studies, including greater health problems. The lack of safe outside play areas is one contributing factor. Academic achievement was found to suffer in overcrowded conditions in studies by American and French researchers. Another study found a higher rate of psychological problems among children living in overcrowded housing.

This is occurring as a generation of middle-class people — weighed down by a poor economy, inflated housing prices and often high student debt — are being pushed to the margins of the ownership market. There will be some 8 million people entering their 30s in the next decade. Those struggling to move up face rising rents and dismal job prospects. It’s not surprising that a growing number of Americans now believe life will be worse for their children.

How do we meet this problem? How about with a sense of urgency? Not that government can solve the problem, but we should consider trying to encourage the kind of entrepreneurs who in the past created affordable “start up” middle- and working-class housing in places like Levittown (Long Island), Lakewood (Los Angeles) and the Woodlands (Houston). Government policy should look at opportunities to create housing attractive to young families, which includes some intelligent planning around open space, parks and schools.

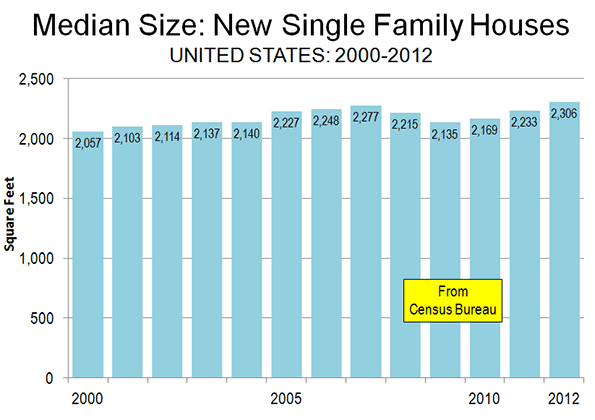

There’s certainly much that government can stop doing. The drive for “smart growth” is increasingly hostile to the very idea of single-family housing. Instead the emphasis, for example in the newly adopted Bay Area plan, is on high-density housing around transit links and virtual prohibition on single-family housing on the urban fringe, without which much higher housing prices — owned and rental — are inevitable. This may appeal to some — especially those in what historian Robert Bruegmann calls “the incumbent’s club: who are already comfortably housed and benefit financially from policy-induced housing shortages. But for the majority of Americans, including immigrants, who would prefer a single-family home, this is bad news indeed.

The situation is worst in high-regulation states with out-of-whack rent and housing cost inflation. Until the 1970s, housing costs were only a little higher relative to income in metropolitan areas like San Francisco and New York compared to elsewhere in the country, staying within the same ratio of roughly 3 to 1. Then came the anti-growth regulatory regime that has doubled house prices relative to incomes, and even more so in San Francisco and San Jose.

But this is not just a California issue. Other states — Oregon, Washington, Maryland — have adopted similar policies. According to Brookings Institution economist Anthony Downs, the housing affordability problem is rooted in the failure to maintain a “competitive land supply.” Downs notes that more urban growth boundaries can convey monopolistic pricing power on sellers of land if sufficient supply is not available, which, all things being equal, is likely to raise the price of land and housing that is built on it.

Generally speaking, as prices rise, single-family homes become scarcer and rents also rise. The people at the bottom, of course, suffer the most, since the lack of new construction, and the inflated prices for houses, also impacts the rental market. Since 1980, the average house price as reported by the National Association of Realtors has moved in near-lockstep with rents, as reported in the Consumer Price Index, except for the worst years of the housing bubble.

To be sure, this does not mean we should build more of the classic suburbs of the 1980s. There needs to be thought as to how to provide housing for people who live near work, or encourage more peopleto work at least part-time at home. It is also imperative that policy provides greater opportunity for people to purchase the housing they prefer and that is also affordable. Technology allows for most jobs to disperse, for tremendous opportunity for overall savings for households. Long linear parks — and even some smaller farms — could provide the critical link to nature and recreation that many households seek.

More than anything we need to recognize that we are not building a reasonable future for the next generation by forcing them to work to pay someone else’s mortgage, that of the landlord. This is the opposite of the American dream and certainly doesn’t reflect the future our parents sought, nor is it one we should bequeath to our children.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.

Creative Commons photo “Signs of the Times” by Flickr user coffeego