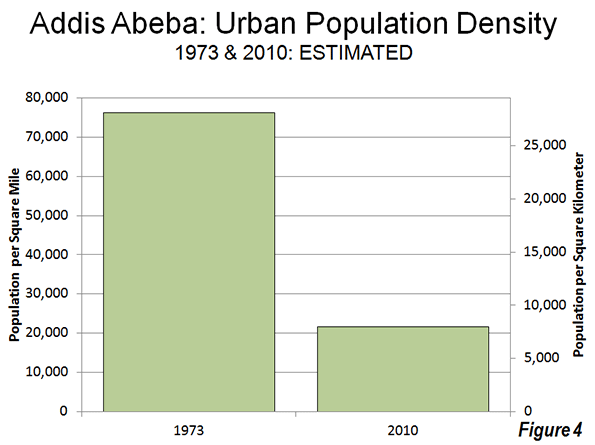

Hong Kong is a city of superlatives. Hong Kong has at least twice the population density of any other urban area in the more developed world, at 67,000 per square mile or 25,900 per square kilometer. The Hong Kong skyline is rated the world’s best by both emporis.com (a building database) and diserio.com, which use substantially different criteria. This is an honor that could not have been bestowed on any city outside New York for most of the 20th century.

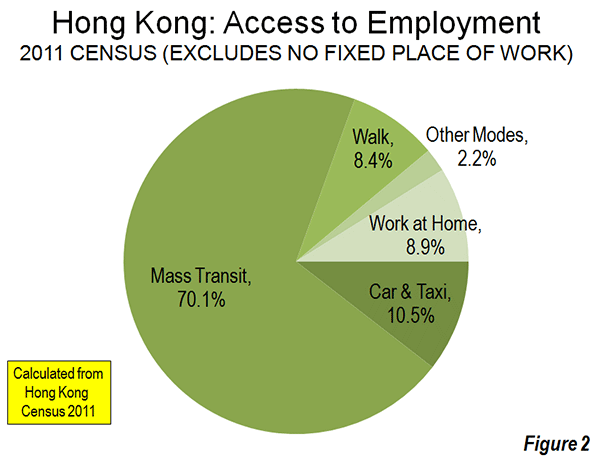

No world city is better suited to mass transit than Hong Kong. Hong Kong may also be the best served — it has the transit usage levels to prove it. According to Hong Kong 2011 census data, 87 percent of combined transit and car work trip travel in Hong Kong is by transit, though this is a small decline from the 90 percent of 2001. This is the highest transit market share of any high-income world metropolitan area.

Change in Work Access Patterns

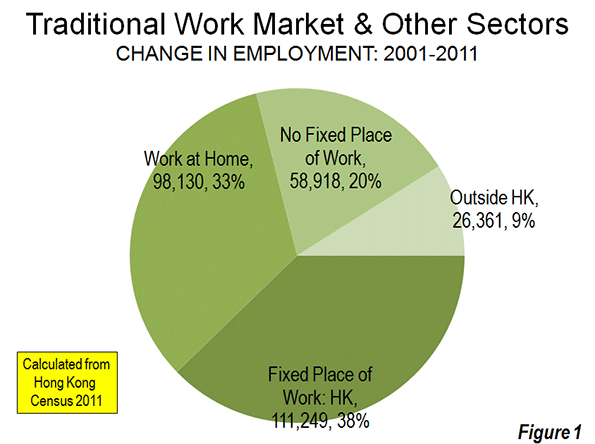

Between 2001 and 2011 Hong Kong’s employment increased nine percent. Most of these new workers (38 percent), however, did not travel to fixed work locations in Hong Kong. Reflecting continuing decentralization and the impact of information technology, 62 percent of the new workers (1) worked at home, (2) had no fixed place of work or (3) worked outside Hong Kong, especially in Macau and the province of Guangdong, principally in Shenzhen (Figure 1). The 2001 and 2011 census data is summarized in the table below.

| HONG KONG WORK ACCESS: METHODS: 2001 AND 2011 | ||||||

| 2001 | 2011 | Change | % Change | Share: 2001 | Share: 2011 | |

| MASS TRANSIT | 2,091,552 | 2,226,818 | 135,266 | 6.5% | 70.4% | 70.1% |

| Bus & Coach | 1,400,770 | 1,188,897 | (211,873) | -15.1% | 47.2% | 37.4% |

| Large Bus | 1,118,388 | 938,467 | (179,921) | -16.1% | 37.7% | 29.5% |

| Minibus (Public Light) | 226,646 | 217,219 | (9,427) | -4.2% | 7.6% | 6.8% |

| Residential Coach | 55,736 | 33,211 | (22,525) | -40.4% | 1.9% | 1.0% |

| Rail | 690,782 | 1,037,921 | 347,139 | 50.3% | 23.3% | 32.7% |

| Metro (Original MTR) | 495,128 | 697,475 | 202,347 | 40.9% | 16.7% | 21.9% |

| Suburban Rail (Original KCR) | 195,654 | 297,416 | 101,762 | 52.0% | 6.6% | 9.4% |

| Light Rail | – | 43,030 | 43,030 | NA | 0.0% | 1.4% |

| CAR & TAXI | 232,978 | 333,192 | 100,214 | 43.0% | 7.8% | 10.5% |

| WALK | 335,859 | 266,574 | (69,285) | -20.6% | 11.3% | 8.4% |

| OTHER | 123,455 | 68,509 | (54,946) | -44.5% | 4.2% | 2.2% |

| TRAVEL TO HK FIXED PLACE OF WORK | 2,783,844 | 2,895,093 | 111,249 | 4.0% | 93.8% | 91.1% |

| WORK AT HOME | 185,367 | 283,497 | 98,130 | 52.9% | 6.2% | 8.9% |

| FIXED PLACE OF WORK | 2,969,211 | 3,178,590 | 209,379 | 7.1% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| NO FIXED WORK PLACE | 188,998 | 247,916 | 58,918 | 31.2% | ||

| WORK IN HONG KONG | 3,158,209 | 3,426,506 | 268,297 | 8.5% | ||

| WORK OUTSIDE HONG KONG | 94,497 | 120,858 | 26,361 | 27.9% | ||

| WORKING RESIDENTS | 3,252,706 | 3,547,364 | 294,658 | 9.1% | ||

| EXHIBIT | ||||||

| Travel to Work in Hong Kong | 2,783,844 | 2,895,093 | 111,249 | 37.8% | ||

| Home, No Fixed Place, Outside HK | 468,862 | 652,271 | 183,409 | 62.2% | ||

| TOTAL | 3,252,706 | 3,547,364 | 294,658 | 100.0% | ||

| Source: Hong Kong Census, 2001 & 2011 | ||||||

| No Fixed Place of Work: Access method not determined | ||||||

The Shift from Bus to Rail: Transit’s overall share of work trip access was 70.1 percent in 2011 (all methods). This is a slight decline from the 70.4 percent in 2001. Over the last decade, Hong Kong has substantially expanded its urban rail system, including major improvements such as a new tunnel under Hong Kong Harbor and the new West rail line (former Kowloon Canton Railway) to Yuen Long and Tuen Mun. I wrote a supporting commentary in the Apple Daily (Hong Kong’s largest newspaper) supporting the rail expansion program in 2000.

The results are apparent in the ridership data. The rail work access market share rose nearly 10 points to 32.7 percent. At the same time, the bus market share dropped nearly 10 points to 37.4 percent. Overall, in a modestly growing labor market, transit added 135,000 new one away work trips.

Car Commuting Up: Cars and taxis experienced a much larger percentage gain, largely as a result of starting from a much smaller base. The car and taxi work trip access market share rose from 7.8 percent to 10.5 percent. Overall, approximately 100,000 more people commuted one way by car to work in 2011 than in 2001. The median incomes of car and taxi commuters are the highest, at more than twice that of rail and bus users.

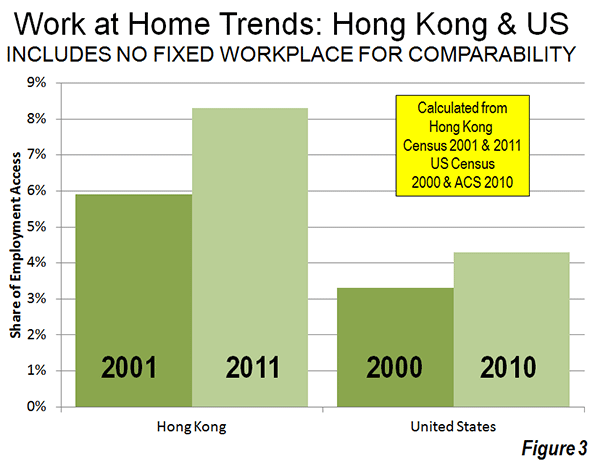

More Working at Home:Hong Kong’s working at home grew the most of any category, rising 53 percent from 185,000 to 283,000 daily. As a result, working at home now accounts for 8.9 percent of work access, compared to 6.2 percent in 2001. Hong Kong’s reliance on working at home was greater than that of the United States in the early 2000s. Over the last decade Hong Kong’s 53 percent increase in working at home was well above the 41 percent increase in the United States. In Hong Kong, 33 percent of new employment was home-based work between 2001 and 2011. This is greater than in the US, where 20 percent of new jobs involved working at home as the usual mode of access between 2000 and 2010.

The Decline of Walking: Given Hong Kong’s intensely high densities, it may come as a surprise that there was a huge loss in walking to work. Nearly 70,000 fewer people walked to work in 2011 than in 2001, as the walking market share dropped 21 percent. In 2011, commuters who walked (and those who used light rail) had the lowest incomes. In 2001, more people walked to work than either travelled by car or work at home. By 2011, fewer people walked to work than travel by car or work at home.

There was also a nearly 55,000 loss in work access by other modes (such as ferries, motorized 2-wheelers and cycling).

Finally, Hong Kong separately categorizes workers without a fixed place of employment and does not obtain information on how they access work. This category experienced an increase of nearly 60,000 from 2001 to 2011.

The Decentralization of Hong Kong’s Labor Markets

The distribution of employment changed little over the 10 years, with Hong Kong Island and Kowloon sectors retaining two-thirds of the jobs. These two areas also have more than one-half of the population. Even so, the Hong Kong labor market followed the global pattern of decentralization. More people traveled outside their home areas in 2011 than in 2001. Among resident workers living on Hong Kong Island and in Kowloon, there was an 18 percent increase in working outside these home sectors. Further, the increase in people with no fixed place of work reflects greater mobility and labor force decentralization.

Jobs-Housing Balance? Not Much

The high density of jobs and population, its short trip distances, its extraordinary transit system and its high transit market share would seem to make Hong Kong a poster city for the jobs – housing balance ("self containment") that urban planners seem so intent to seek. The data indicates no such thing.

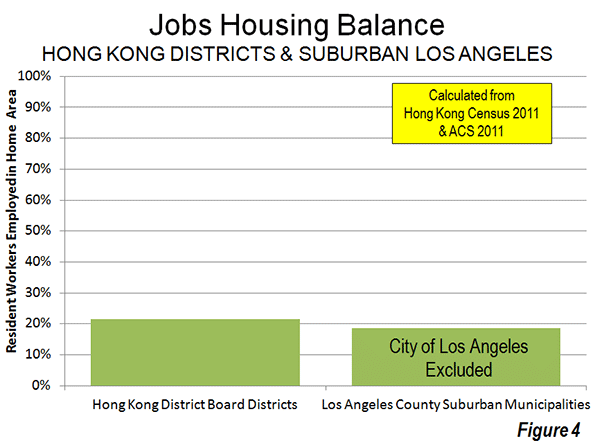

Hong Kong’s 18 districts illustrate a comparatively low rate of self containment. Only 21.4 percent of working residents are employed in their home districts, including those who work at home. This is only slightly higher than in highly decentralized suburban Los Angeles County, where 18.5 percent of resident workers are employed in their home municipalities. With far lower population and employment densities and a 50 percent smaller geographical size, the suburban municipalities of Los Angeles County (city of Los Angeles excluded, see Note below) nearly equal the local-area jobs-housing balance of the Hong Kong districts (Figure 4).

This tendency to work away from home districts contributes to Hong Kong’s extraordinarily long average commute times. In 2002, the average work trip was 46 minutes, longer than any high-income world metropolitan area except Tokyo. By comparison, Dallas-Fort Worth, with a similar population and a population density less than 1/20th that of Hong Kong, has an average work trip travel time of 26 minutes. Los Angeles, with its world-class traffic congestion has a work trip travel time of 27 minutes, principally because its automobile dominant commuting is much faster than Hong Kong’s world class, rail based transit system.

These data, both in Hong Kong and Los Angeles, show that, within a metropolitan area (labor market), people will tend to seek the employment that best meets their needs, just as employers will hire the people best suited to theirs. Within a labor market, this can be anywhere, subject to the preferences of people and employers, not of planners. This is the basis of former World Bank principal planner Alain Bertaud’s caution that a city’s economic efficiency requires … avoiding any spatial fragmentation of labor markets.

The Mistake of Trying to Emulate the Unique

It is a mistake to think that urban planning can emulate Hong Kong. Besides its superlatives, Hong Kong did not become so dense as a result of urban planning or the unfettered preferences of people (market forces). Hong Kong’s uniqueness is the result of unique geo-political influences. This history forced an unprecedented accommodation of millions in a small space, especially in the third quarter of the 20th century when it stood as a capitalist island in the midst of a Communist sea.

Hong Kong is unique and will be for a long time.

Note: The city Los Angeles has a very high jobs-housing balance (61 percent). However, this is largely due to its huge geographic size (more than 40 times the average suburban jurisdiction).

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

—-

Photo: West Rail Line, Tin Shui Wai Station bus interchange, Yuen Long (by author)