Cairo, Egypt’s capital, has long had some of the highest neighborhood population densities in the world. In the 1960s it was reported that one neighborhood had a density of 353,000 people per square mile (136,000 per square kilometer). The most recent data from the Egypt’s statistical authority (the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics or CAPMAS) indicates that within the Cairo governate (the province in which the municipality of Cairo is located), the overall urban population density is 117,000 per square mile, or 45,000 per square kilometer. This means that urbanization in the Cairo governate is more than 1.5 times the population density of Manhattan (in New York city) and the ville de Paris.

In recent decades, government officials have undertaken a program to encourage people to decentralize their living and work arrangements, and to move to several new towns in the area.

Overall, the governates that comprise the Cairo metropolitan area have a population of approximately 20.5 million, according to a CAPMAS 2012 estimate. This is approximately the same size of metropolitan areas such as New York and Mexico City. The Cairo metropolitan area is comprised of three governates, which are principally urban, but which also contain millions living in rural areas:

The governate of Cairo (Al Qāhirah) is the largest of these jurisdictions. Parts of the Cairo governate and the Giza government would be considered in the urban core, but the political jurisdictions in Cairo do not lend themselves well to conventional core versus suburban designations (Note 1). The Cairo governate is located on the east bank of the Nile River, and spreads many kilometers, especially to the East and South. This area includes the Cairo international airport and Heliopolis, one of the most affluent areas in the Cairo metropolitan area. The governate of Cairo also includes "New Cairo," an attractive new town located in the southeastern quadrant. This area includes a number of university campuses, multi-story condominium buildings and detached housing. Eventually, New Cairo is expected to have 4,000,000 residents, though the new town is little more than a decade old and still has a modest population of approximately 125,000.

New Cairo: University

The governate of Giza (Al Jīzah) is located on the west bank of the Nile River and, in reality, constitutes a continuation of the urban core. Giza is home the Great Pyramids, which rise on a hill from the western urban fringe. Giza is also home to considerable informal housing development much different than generally found in other megacities. Much of the development is high rise, with concrete block buildings rising seven and more stories from the streets. Generally, the streets are so narrow and irregular that they are not shown on local maps. The governate of Giza also includes the "6th of October" new town, located on the west side of the hills on which the Great Pyramids stand. Eventually, 6th of October is expected to have a population of 3,000,000, though it appears to be less than 500,000 today. The governate of Giza also includes the Sheihk Zayed new town. These new towns have commercial activities, multi-story condominiums and detached housing.

Sheikh Zayed: Detached Housing

Giza: Informal Housing

The governate of Kalyoubia (Al Qalyūbīyah) is located to the north of the Cairo and Giza governates. Unlike Cairo and Giza, Kalyoubia has a majority of its population living in rural areas. However, the continuous urbanization of Cairo stretches into the governate and includes more than 1.5 million people, much of it in the municipality of Shubrā al-Khaymah.

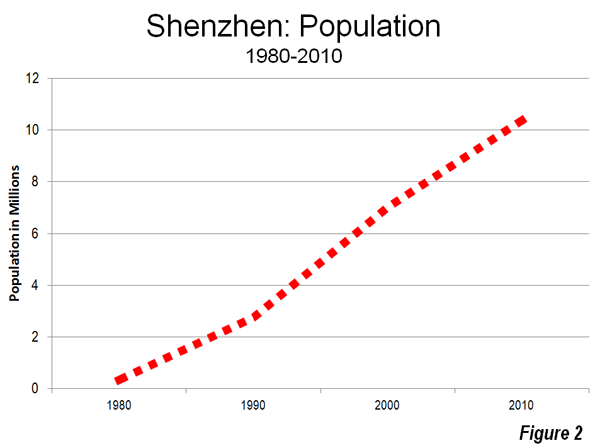

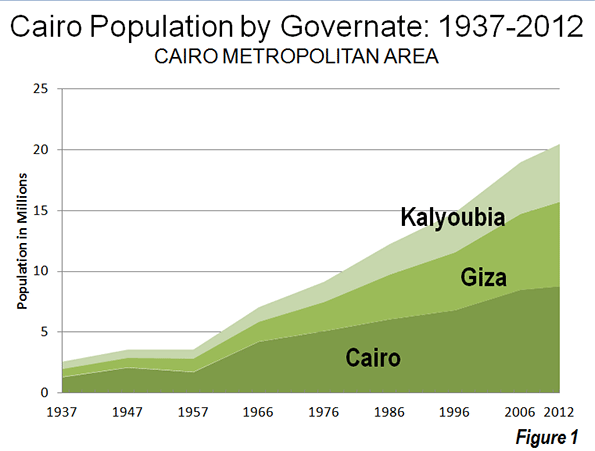

Slowing Growth: Like many of the developing world’s megacities, Cairo has experienced its strongest growth in the half century after World War II. In 1937, the metropolitan area had a population of under 3 million. This more than doubled to 7 million by 1966, and again to 14 million by 1996. From 1996 to 2012, the metropolitan area added 5.5 million people (Note 2). However, more recently, the growth rate has slowed considerably. Between 1996 and 2006, metropolitan Cairo added 28 percent to its population (an increase of more than 4,000,000). However the 2006 to 2012 rate would indicate that by 2016, Cairo is likely to add only 13 percent to its population (approximately 2,000,000 people).

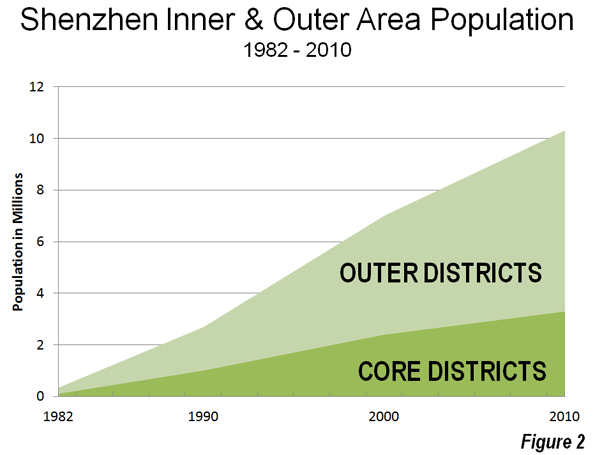

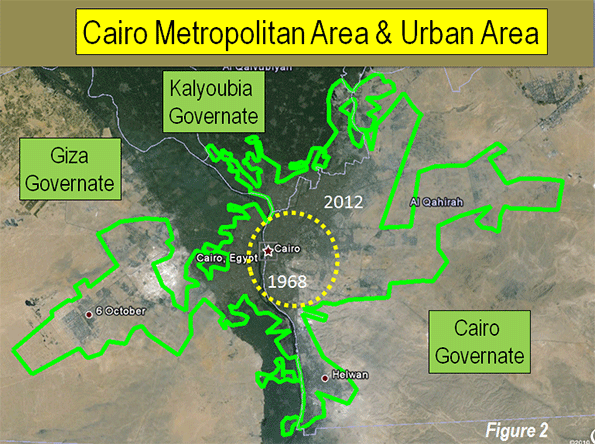

While the governates of the Cairo metropolitan area do not lend themselves well to urban versus suburban population analysis, Cairo clearly has expanded geographically as it has added population. The more central governates of Cairo and Giza have continued to grow, however much of the growth has been in peripheral areas, such as New Cairo, 6th of October and the Helwan area, south of Cairo on the Nile (in the Cairo governate).

Where the Growth is Occurring: Even so, the governate of Cairo accounted for only 19 percent of the metropolitan area’s growth from 2006 to 2012, down from 34 percent in the 1996 to 2006 period. The governate of Giza had the greatest growth between 2006 and 2012, at 47 percent of metropolitan growth, an increase from the 39 percent of 1996 to 2016. The governate of Kalyoubia accounted for 34 percent of the growth from 2006 to 2012, an increase from 26 percent between 1996 and 2016 (Figure 1).

Cairo’s Physical Expansion: Even though the suburban versus core analysis is difficult to gauge from governate data, a paper by Mootaz Farid and Hatam Al Shafie of Cairo University contains depictions of the urban footprint from 1943 to 1982. In each of the depicted years, the continuous urbanization of Cairo covers only a miniscule share of the present urban footprint. Figure 2 provides an estimate of the urban footprint in 1968 compared to the 2012 urban footprint, indicating that much of the growth was on the periphery.

The Key to Decentralization: The key to making the new towns successful in attracting more residents lies with the dispersion of employment. There is a wealth of international experience to indicate that "self-sufficient" new towns really cannot be self sufficient if they are within commuting distance of the rest of the urban area. In the case of Cairo (as elsewhere) it will prove critical to ensure that there are substantial local employment opportunities for new town residents, although it is likely that a serious degree of self sufficiency may prove difficult to achieve.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

Top Photograph: The Great Pyramid (Giza). All photos by author

——

Note 1: In the past decade there have been reorganizations of governates in the Cairo metropolitan area. This article uses three present governates for all years.

Note 2: Earlier population data is from http://statoids.com/ueg.html.