In 2009, the number of repossessed autos increased to 1.9 million. The number of homes under foreclosure varies from month to month, but the 2009 total was about 2.8 million. For 2010, it seems that a million new foreclosed homes would be conservative, with a large percentage in California. Miss a few payments on an auto loan and you may wake up to an empty driveway. On the other hand, repossession of your home is a long drawn out process.

What kinds of communities have been hardest hit with foreclosures? Tom Cusack, a retired federal housing manager in Portland, tracks the issue via his Oregon Housing Blog. This summer, he was quoted in the Portland Tribune, saying “The foreclosure activity that is occurring in suburban markets in Oregon is unprecedented. It’s affecting not just rural areas, not just inner-city neighborhoods, but suburban neighborhoods, probably more substantially than any time in the past.”

Daniel Ommergluck of Georgia Tech also studied this situation. His findings, he says, contradict “…some suggestions that the crises was primarily centered in suburban or exurban communities.” It concluded, “The intrametropolitan location of a zip code appears to have been a less important factor in REO (real estate owned) growth than the fact that a large amount of development in newer communities was financed during the subprime boom.”

Decades ago, a young couple would have had to save for many years to accumulate the considerable down-payment to buy their first home, and the prospect of losing that home to foreclosure would have been devastating. With the more recent “easy financing,” though, there has been little to risk. The low effort to move into that new housing development has meant less “emotional” investment. When home prices escalated beyond reason in the years prior to the crash, it left many home buyers over-exposed, specifically because of the easy mortgages.

The local economy also determines which suburbs suffer the most. Certainly homes in prosperous Houston or San Antonio that did not ride the absurd price increases fared much better than Detroit, with its bleak employment picture, where homes are imploding in value.

Historically, the U.S. suburban home buying market is somewhere between 70% and 80% higher volume than the urban market. In other words, for every ten homes sold, seven or eight of them are likely to be suburban. So, it would stand to reason that the foreclosure crisis would be focused in the suburbs. Yet suburban vs. urban data on the subject is scarce.

It’s probably more reasonable to assume that the local employment situation would have a larger effect than whether a community is urban or suburban. For example, when the Ford Plant in urban St. Paul closes, there will be 750 employees out of work and at risk of eventual foreclosure if the job market remains depressed. The residential area abutting the Ford plant is actually very nice, suggesting that many of the workers might live in the nearby city, not in the suburbs. Several miles from the Ford Plant is the suburb of Eagan where Lockeed Martin will close down their operation and put some 400 highly paid people out of work. These newly unemployed workers also may ultimately end up with their homes in foreclosure if they cannot gain highly paid employment elsewhere. Thus suburban vs. urban foreclosures are related to a very localized economy.

There is, however, a greater menace to the suburbs than home foreclosures. It is when an entire development is foreclosed and becomes bank owned. Since the urban foreclosure is likely on a home that has been sold many times since the development — let’s call it ‘Jones Addition’ — was first built in 1925, the developer going broke is meaningless to the urban dweller.

However, when ‘Jones Acres’ in Pleasantville was opened just five years ago, and phase one sold out with the beginning of phase two of 12 phases just started at the time of the crash, a very different and dangerous scenario arises. You see, Jones Acres is comprised of 500 lots. Of those, perhaps 40 were purchased by new suburban home buyers trusting that the amenities would be built as planned and promised.

When President Bush announced that we had a 700 billion dollar problem and needed to bail out the banks, those same financial institutions essentially called the loans, which closed down much (probably most) of the nation’s developers. Land was no longer secure, and the development repossessions began. Without the banks funding, developers could not afford to properly maintain the grounds, associations failed, and eventually the banks were the new owners.

Here in Minnesota, I know of few suburban developments that have not been foreclosed on. This would seem to be a greater threat to the future of the suburbs than individual homes being lost. Yet very little attention has been paid to the volume of bank owned developments. Much of the suburban land was purchased under contracts to farmers that took the land in phases. If a major builder committed to taking down the 500 lots in Jones Acres, and placed a million dollars in initial money ($2,000 a lot for the land), and after 40 lots decided to walk away, it left the farmer holding the land now likely taxed much higher and in danger of foreclosure. It made sense in many scenarios for the major builder to walk away and lose its lot deposits. Later on, if the development failed and the bank needed to unload the property, another major builder might be able to pick up the lots at 10 cents on the dollar, and just sit on the property for years until the housing market starts to recover.

Since the recession began, a group of us approached banks with an offer to review the approved plans and re-plan some idle developments more efficiently and sustainably. This state of limbo would have been an excellent time to redesign the land into a much more sustainable (and profitable) product with little outlay from the financial institution. We could not find a single bank that was interested in adding value.

Often the initial developer imagines the details of a neighborhood: the amenities, the architecture, the landscaping, and the marketing. What happens when a bank takes over? The banker most likely lacks this forward vision, and sells the development later to a buyer who offered 1/10th of the initial land cost for an approved platted development. Bah humbug, this buyer says, who needs a front porch, parks are for drug dealers, and if streets were meant to have trees, then the lord would have planted them there! The result is a highly visible, low value community.

Cities approve developments based upon relationships. The recession eradicated so many promises that may now never be realized. Foreclosed homes in the cities or in the suburbs are less of a problem than foreclosed developments… and in this case, the suburbs lose – big time!

Photo by Sean Dreilinger: One of two adjacent bank owned homes.

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and Neighborhood Innovations, LLC. He is author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable and creator of Performance Planning System. His websites are rhsdplanning.com and performanceplanningsystem.com.

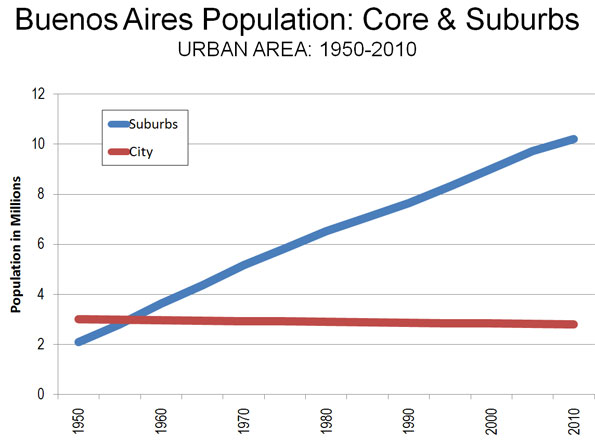

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.