The foreclosure crisis has been devastating for millions of Americans, but it has also impacted many still working as before and holding on to their homes. Even a couple of empty dwellings on a street can very quickly deteriorate and become a negative presence in the neighborhood, at the least driving down prices further, sometimes attracting crime. Untended pools can allow pests to breed. Many animals have been abandoned and shelters report overflowing traffic. The resulting impacts on local governments have been particularly visible, as property tax assessments have fallen and revenues have also gone south.

Less obvious is the impacts on home owner associations [HOAs], whose revenues have also taken a hit, albeit for rather different reasons. For the most part, HOA dues are not a function of the value of the home but rather the need to cover the costs of maintaining the common interests of the association: landscaping, security and so forth. These tend to be fixed, even if the values of the homes collapse, and may even rise if dwellings are empty and untended.

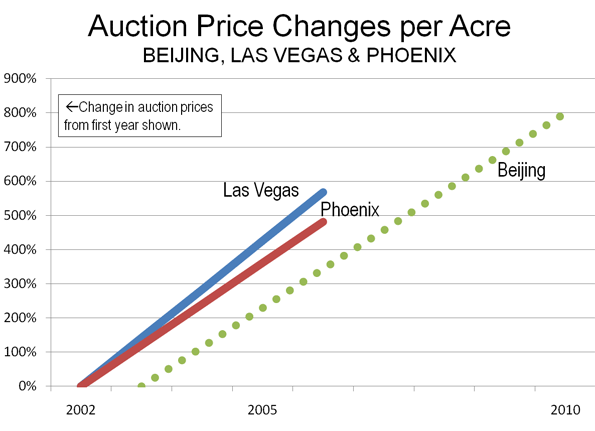

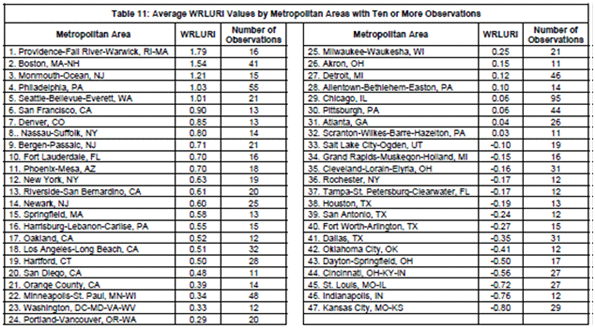

Many HOAs, especially in the newer metropolitan areas like Phoenix and Las Vegas where foreclosures have been most concentrated, have taken a beating because the number of households paying into the association has been depleted, quite badly in some instances. The problem seems, from press reports, to cover the economic spectrum. Low-income first-time buyers may stop paying their dues as an economy measure, while more affluent owners are more likely to have pulled cash from their home and are walking away from their debts. There are also thousands of empty homes that were purchased as investments at the height of the boom and may have never even been occupied.

The foreclosure debacle is now old news, but the HOA situation is receiving attention because association boards are now aggressively trying to recoup their debts, even from those who have walked away from their mortgages. The debt, they argue, is attached to the individual, not to the dwelling, and is being turned over to collection agencies. Now, this is hardly a novelty. Municipalities have been turning household utility debts over to third parties for years, often with some success, and without a murmur of protest. So why is it different if HOAs do it?

The answer is that HOAs are extremely unpopular with two vocal constituencies. The first is the academic community, and its hostility is part of the professional opprobrium that is heaped on gated communities, privatization and pretty much anything connected with suburban development. Interestingly, while the design aspects of gated communities have caught the attention of planners and urbanists, relatively few have focused on the dimension of governance. Those that have written on the topic have tended to be critical of private clubs that are seen to exist at the expense of the municipal collective. For what its worth, I don’t think I’ve ever known of an academic colleague who lived in an HOA, in contrast to the bulk of my students, who live in one or grew up there.

The second constituency is more rowdy. Academics just disdain HOAs, but this group is committed to exposing them as a vast conspiracy to subvert the American way of life. This may sound like another version of contemporary “Teamania” but it is has been around for at least the past decade, during which time I’ve been monitoring Internet posts and the like. To this group, any restriction on personal freedom — from the color of one’s drapes or exterior paintwork through the display of the national flag — is clearly anathema.

Early this year, my research on neighborliness in HOAs was covered in the local paper, and by the end of the day there were dozens of online posts. In response to the basic finding — that there is little fundamental difference between HOA and traditional neighborhoods — we received a torrent of angry responses. With a single exception, they all dismissed the findings out of hand, using an example of someone’s experience (rarely their own) to prove the point, at least to their satisfaction. One reader even tracked down my email address in order to demand an assurance that no public funds were used to promote this nonsense.

Like much in contemporary American politics, this leaves me confused. I don’t understand why an exclusive residential association, freely entered into, with explicit rules that are presented at the outset, offering services-for-cash, is un-American. After all, this is in contrast to a municipality that levies taxes for services from which one cannot opt out (if one has no children in the schools, for instance) and which may not be available to all (such as public transport), and which could easily be seen as a redistributive institution, an example of that socialism we keep hearing so much about.

For the record, I am happy to pay my property taxes for services I don’t receive — its just part of the social contract. Nor do I live in an HOA. But I can understand why our research indicates that most people who live in them do prefer them (and, for example, often move from one HOA to another). Rather than displaying the angst of those who seem to get nervous if anyone tries to step on their toes, these residents embrace belonging to a small polity in which they have a voice. And we should remember that rules, like fences, make good neighbors. As these neighborhoods become more diverse, traditional and non-traditional households alike can find reassurance in the behavioral conformity demanded of neighbors by an HOA.

This brings us back to the recent stories about management boards ‘hounding’ those who have not paid their dues. Similar accounts have shown up for years, and the thrust is always the same: punitive, out-of-control boards attack those already in financial distress. There is clearly a lot of the latter to go round, but it’s hard to see why HOAs are much different than any other organization that is looking at a handful of bad debts. Are the HOAs the victims here? Absolutely not. Many embraced the housing bubble, and permitted speculators to buy in, even though they had no intention of living in the properties. At the height of the madness, up to one third of all housing transactions in Phoenix were initiated by out-of-state buyers who drove up home prices precipitately, and eventually caused the median house price to double. This has since corrected. All CC&Rs (the rules of the HOA) that I have seen dictate however that the purchaser must live in the property and that rental units are not permissible. So, like all the other players, the HOA boards liked the price increases so much that they ignored their own rules and looked the other way, a lapse for which they are now paying the price.

Still, it would be a mistake compounding a mistake to climb on the anti-HOA bandwagon, now joined by the ACLU, which has recently joined the fray over a fight about a homeowner’s right to fly the Gadsden flag (motto: “Don’t step on me”). Libertarians should recognize that no-one has ever been forced to live in an association and that whipping up the wrath of state legislatures to control HOAs is a bad idea: it encourages even more government intervention, and it messes with the neighborhood, a form of governance that the vast majority rightly supports, even in HOAs.

Andrew Kirby has written about HOAs on several occasions, including the 2003 edited volume “Spaces of Hate”. He most recently wrote about ‘The Suburban Question’ on this site in February.

Photo by monkiemag