When you get that morning cup of Java, do you desire the minimal flavor? How about your career, do you desire the most minimal pay check or profits or the most mundane of positions? Let’s assume for some reason that you said ‘No, you would always want to strive for something better than the minimum’.

You now have three hats in front of you, one says “planner” on it, one says “engineer,” and the last one says “developer”. When you put on the “planner” hat, your job is to develop and enforce a set of rules that will guide the development of a city. You suggest to the council a set of standards that recommend the minimum dimensions and areas for residential or commercial projects that are brought in for approvals. Council and planning commission members will argue a bit, but eventually they will decide on what the minimum controls will be within the regulations you will be writing…

Under the “developer” hat, you just bought 100 acres from the bank at a steal, yet it still cost over two million dollars, and that monthly interest payment is going to be painful. You cannot begin to sell any lots until you get preliminary plat approval, so until then, money bleeds out, not in. You cannot form a business plan until someone lays out your site. You look at the local engineering firm and see they offer “land planning” as one of their areas of expertise. They have a large impressive office with lots of computer screens flickering away. Obviously, they must be experts on land planning who can deliver a unique land development that will provide a market edge that makes your development as successful as possible. So you just sign here on their contract for services…

Wearing that “engineer” hat, you look over your production floor. It was once bustling with activity, but now those screens are flickering with employees trying to look busy in fear that a layoff is coming. Luckily, you have a developer coming in with that 100 acre project. You really like laying out subdivisions, and you look forward to using that new software you just bought to automate the process. Next week, you’re scheduled to meet with the developer, who is going to present a sketch plan on the site. You’re ready, with your new software that promises an LPM (lots per minute) ratio of up to 250 lots per minute. With this new tool you can easily lay out that new development in just an hour. Since this is only a sketch plan meeting, you just need a quick picture to get things started.

To make sure you are up to date on the latest regulations, you check the web site of the city for the latest minimums to enter into the software. You use Google Earth to trace in the boundary of the site, because you do not have the time to survey the land, nor does the developer want to spend any money at this point until he knows the city will give him sketch plan approvals. Besides, you threw the initial planning in for free to lure in the developer and get those lucrative engineering fees.

After obtaining a rough estimation of the site from Google Earth, you use your latest technology to generate streets and lots almost as fast as you can move the mouse across the screen. Something that used to take days is now virtually instant. Each lot appears at the exact minimum setback, with the exact minimum side yard, and at the exact minimum square footage. Wow! You are quite happy to tell the developer that he’s got 400 lots on his site.

Slapping on the developer’s hat you use the sketch plan to create your financial projections, cautiously of course, because you have not been given sketch plan approval yet. But clearly you are about to make a ton of money.

Wearing the planner’s hat, at the planning commission meeting you present “Oak Ridge”, the proposal for the 100 acres. After hearing complaints about the monotonous design, you explain that Oak Ridge follows the regulations that the planning commission had agreed upon: every minimum has been met. Reluctantly they approve the sketch plan for Oak Ridge.

Wearing the developer hat you could not be more pleased. Imagine the profits that the lot sales will bring, especially because you got the land so cheap! Never in your wildest dreams had you thought you could get 400 lots approved. The next day you put down a deposit to order that Bentley you always dreamed about.

A few weeks later— wearing the engineer’s hat — you sit down with the actual boundary survey, which is much more accurate than the Google Earth data you used for the sketch plan. You find that the boundary was not even close to what you traced. The surveyor points out the wetlands that will take up about a quarter of the land. He also explains that there is evidence of the pipeline easement. What the ^%$#… ? What pipeline easement? Oh, yes, you remember that Google Earth does not show easements, an honest mistake.

You explain to your staff that the developer wants to explore a low impact development with surface flow. They tell you that the software only automates pipe networks; surface flow calculations are not automated. You direct them to forget the low impact stuff, too much liability and it will add too much manual labor time.

Wearing the developer’s hat you sit down, ready to be presented with the preliminary plat of Oak Ridge. It is a wise choice to be sitting down, because the 240 lot preliminary plat comes as a bit of a shock! What happened to the 160 extra lots we got approved? The engineer explains that was just a quick sketch. By the time the actual boundary was provided, and what with the wetlands and the steep slopes, well, it just had to be made to work.

The engineers explain to you they held every lot to the absolute allowed minimum and that 240 lots is not bad at all. Your vision of the plan blurs and an image of your financial partners and lenders appear, along with thoughts how you are going to pay for that Bentley you picked up last week.

No more need of hats. You now have a picture of a scenario that repeats itself all too often in the land development process. We live in a world dictated solely by minimums. The new buzz-phrase is “a forms based regulatory process”. Is this not just another way to assure that there is a minimum relationship between manmade structures? Notice how architecture did not enter this story… That will not be a factor until later on, as the lots are sold – why worry at the onset of the development?

There are a variety of software packages that automate land development and are used by virtually every engineer in the world. These packages have been developed by firms whose main purpose is to automate engineering. It is so simple to throw in automation for lot geometry. Some of the firms that provide this automation are quite large – billion dollar corporations, that earn profits by using those minimum dimensions allowed by regulations and providing tools that cut the process of producing land developments and engineering drawings from months to minutes.

In this process of progress, we got lost. To have the concept of an LPM ratio of 250 lots per minute is like saying we will layout 250 homes at $200,000 each in 60 seconds. This equates to $833,333 in housing for each second. The development is likely to sit for a few centuries or more, and each home is likely to have 3 people living in it. The average home sells every 6 years, so the living standards of 25,000 people will be set in those 60 precious seconds. How much thought do you think someone laying out 4.16 homes per second will give towards reducing housing costs, eliminating monotony, views from the homes, curb appeal, low impact drainage, long term values, ecology, preserving natural contours and vegetation?

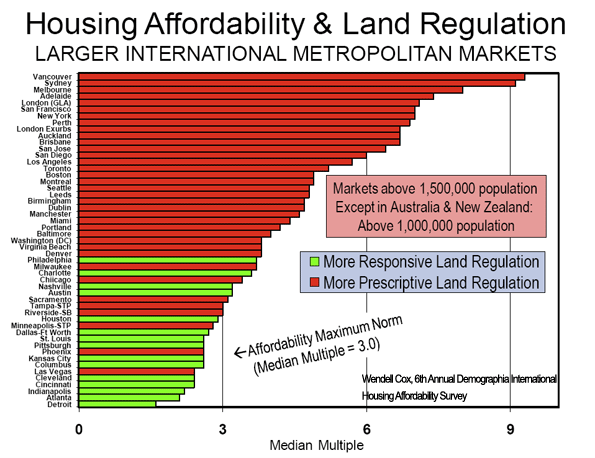

If you want to speed towards a completely unsustainable world, join virtually everyone involved in the land development process. They are already doing that quite well, thank you. We need a complete overhaul of the land development process. Smart Growth is a solution for a limited envelope of development. It will make an impact, but the impact will only be a small ripple in a very large pond. A prescribed set of stringent rules cannot apply to every development situation, thus a monolithic strict set of rules is not a fix for both urban and suburban living.

If you do not seek minimum taste, nor minimum income potential or a minimum position in life, then why would you be remotely satisfied living in the minimal development pattern that creates a minimal city?

When we lay out and build new cities and rebuild existing ones, let’s take the time, thought, and consideration to maximize living standards and assure the successful placement of all businesses that will thrive in the developed future. Perhaps then, we could call this maximized future “sustainable”.

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and Neighborhood Innovations, LLC. He is author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable and creator of Performance Planning System. His websites are rhsdplanning.com and performanceplanningsystem.com.

In 2006, the owner had refinanced the house with a $308,750 loan, indicating a value more than triple that of comparable housing in much of metropolitan America.

In 2006, the owner had refinanced the house with a $308,750 loan, indicating a value more than triple that of comparable housing in much of metropolitan America.