During the first ten days of October 2008, the Dow Jones dropped 2,399.47 points, losing trillions of investor equity. The Federal Government pushed TARP, a $700 billion bail-out, through Congress to rescue the beleaguered financial institutions. The collapse of the financial system was likened to an earthquake. In reality, what happened was more like a shift of tectonic plates.

*******************************************

In September 2009 the Fed proclaimed “The Recession is Over.” President Obama said his Stimulus Package saved the US economy and his international actions have “brought the global economy back from the brink.” Vice-President Biden declared, “The Stimulus Package worked beyond my wildest dreams.” I feel so much better. Living in California, I must have missed these events.

If the recession is over, why is unemployment in California 12.2%? (Functional unemployment, the real number, is closer to 16%). In decimated areas like the Central Valley, unemployment is at Great Depression levels of 26%. If the economy was saved, why do our homes continue to lose value? And it is not just “our homes” that are impacted. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was forced to rent out his Larchmont, N.Y., home after it failed to sell. President Obama’s Chicago home, purchased for $1.65 million with a $1.3 million jumbo mortgage at the height of the real-estate bubble is now worth less than $1.2 million according to an estimate by Zillow.

The recession may be over but Americans are now experiencing The Roller Coaster Recession. Like a roller coaster chugging its way up to the top, home values climbed between 2002 and 2007. Beginning in the fall of 2007, home values declined, first slowly but inexorably until they bottom out and began to climb again. Have we bottomed out? The Atlantic screamed, “Home sales soared 11% in June”.

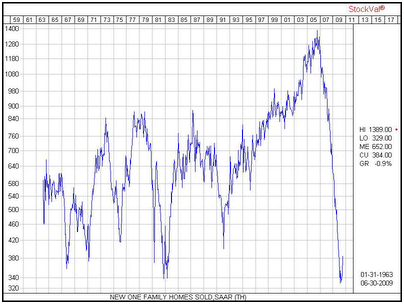

Not so fast. Like the cars in a roller coaster, the first cars will begin to climb out while the last cars are still screaming downward at top speed. The Commerce Department reported sales in August rose a tepid .07% in August. What they did not highlight is that new home sales of 429,000 are at historical off the chart low compared to the last 50 years (see chart below).

Such is the case with the Roller Coaster Recession. In California’s roller coaster ride the first car, The Inland Empire, crested the top in 2007. When pink slips were issued, these homeowners did not have deep pockets to sweat it out. All of their savings had been plowed into their down payment. When values declined, they had no staying power. They were gone in the first wave of foreclosures.

Meanwhile, the rear car, Coastal California, continued to climb in value seemingly immune to the problems inland. The reason was staying power. The residents of tony Corona Del Mar were able to dump their third car, the Range Rover to keep solvent. When that ran out, Coastal California tapped their savings and finally used their equity lines to maintain their high mortgage payments while they waited for a buyer. But it is 2009 and the buyers have not materialized. More Jumbo Loans are falling behind in their payments. Watch the 60-day delinquency rate on prime Jumbo Loans. According to First American Core Logic, Jumbos in default jumped to 7.4% in May versus 4.9% for conforming loans

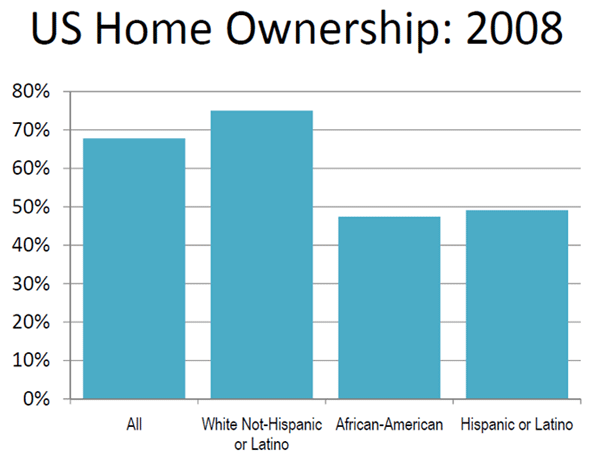

Like our proverbial roller coaster, now it’s the turn for the first cars to rise. As the Inland Empire seems to have bottomed, Coastal California is still racing downward. There are 200 homes for sale between $1.5 and $3 million in ritzy Corona Del Mar. Even with a hefty 25% down payment, a $2 million property will require a $1,500,000 mortgage. Today’s lenders will require proof that the borrower can afford the $7,500 per month mortgage payment. They will demand a W-2 or 2008 tax return showing at least $22,500 per month in income to support a 30% housing expense ratio.

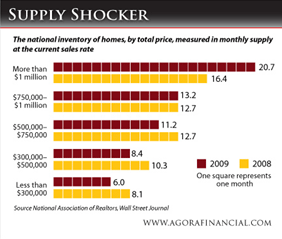

The reality is there simply are not enough buyers earning $250,000 per year to buy up the 200 homes in Corona Del Mar. The current inventory will take 17 months to sell out but, as the recession continues, more homes are posting For Sale signs each month. Coastal California has not yet seen their bottom and they are still heading down at a rapid pace.

Our national leaders may proclaim the end of the recession, but Californians have no reason to party. The Stimulus Package that shipped $50 billion to California was a one-time windfall that delayed but did not end California’s structural $26 billion budget deficit.

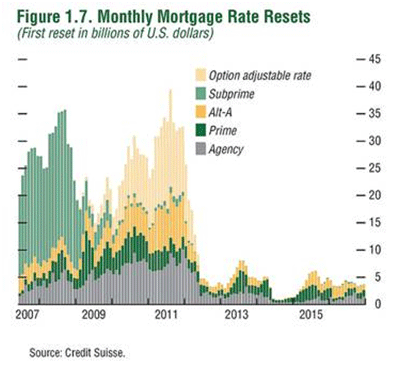

Add to that the “Mortgage Armageddon” that is scheduled to hit next February. As the sub-prime mortgage defaults subside, the Option ARMS (adjustable rate mortgages) and Prime ARMs will begin to reset in early 2010 (see chart). This is not a working class but primarily a middle and upper-class problem. It is more a coastal than inland crisis; in New York terms, more Larchmont and less exurbia.

There is a problem, however, with dinging the rich. They are the very folks expected to spend in our consumer-driven economy and invest in new ventures. If they have to re-route more dollars to mortgage payments, they not going to be able to help the economy.

The Roller Coaster Recession will see more rises and dips before a sustainable recovery comes to California and other high-priced marekts. Those in the first car, like The Inland Empire, have nearly completed their ride. Any remaining dips will be minor in drop and brief in duration. But the genteel folks in the last car, in places like Coastal California, have another precipitous drop in front of them. This may come as a surprise to those believing the headlines that the recession was over. The wild ride for many is hardly over yet.

***********************************

This is the fourth in a series on The Changing Landscape of America. Future articles will discuss real estate, politics, healthcare and other aspects of our economy and our society.

Robert J. Cristiano PhD is a successful real estate developer and the Real Estate Professional in Residence at Chapman University in Orange, CA.

PART ONE – THE AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY (May 2009)

PART TWO – THE HOME BUILDING INDUSTRY (June 2009)

PART THREE – THE ENERGY INDUSTRY (July 2009)

Environmentalism has further accelerated the trend for the shrinking of the British home. The emphasis upon the Rogers-style compact city has been trumpeted by the Green Party and other environmental lobby groups because higher densities and small build theoretically cause less carbon emissions and use up less non-renewable sources of energy.

Environmentalism has further accelerated the trend for the shrinking of the British home. The emphasis upon the Rogers-style compact city has been trumpeted by the Green Party and other environmental lobby groups because higher densities and small build theoretically cause less carbon emissions and use up less non-renewable sources of energy.