Both the world and the nation remain in the midst of the greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression. But with all the talk of “green shoots” and a recovery housing market, we may in fact be about to witness another devastating bubble.

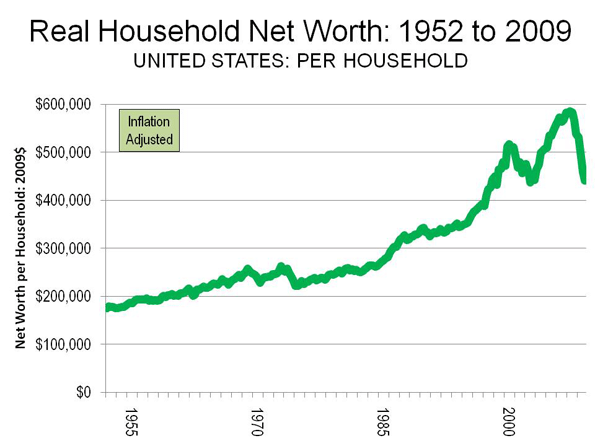

As we well know, the Great Recession was set off the by the bursting of the housing bubble in the United States. The results have been devastating. The value of the US housing stock has fallen 9 quarters in a row, which compares to the previous modern record of one (Note). This decline has been a driving force in a 25 percent or a $145,000 average decline (inflation adjusted) in net worth per household in less than two years (Figure 1). The Great Recession has fallen particularly hard on middle-income households, through the erosion of both house prices and pension fund values.

This is no surprise. The International Monetary Fund has noted that deeper economic downturns occur when they are accompanied by a housing bust. This reality is not going to change quickly.

How did the supposedly plugged-in economists and traders in the international economic community fail to recognize the housing bubble or its danger to the world economy? It is this failure that led Queen Elizabeth II to ask the London School of Economics (LSE) “why did noboby notice it?”. Eight long months later, the answer came in the form of a letter signed by Tim Besley, a member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England (the central bank of the United Kingdom) and Professor Peter Hennessey on behalf of the British Academy.

The letter indicated that some had noticed what was going on,

But against those who warned, most were convinced that banks knew what they were doing. They believed that the financial wizards had found new and clever ways of managing risks. Indeed, some claimed to have so dispersed them through an array of novel financial instruments that they had virtually removed them. It is difficult to recall a greater example of wishful thinking combined with hubris.

The letter concluded noting that the British Academy was hosting seminars to examine the “Never Again” question.

Among those that noticed were the Bank of International Settlements (the central bank of central banks) in Basle, which raised the potential of an international financial crisis to be set off by a bursting of the US housing bubble. Others, like Alan Greenspan, noticed, telling a Congressional Committee that “there was some froth” in local markets. Others, across the political spectrum, like Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, Thomas Sowell and former Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor Donald Brash both noticed and understood.

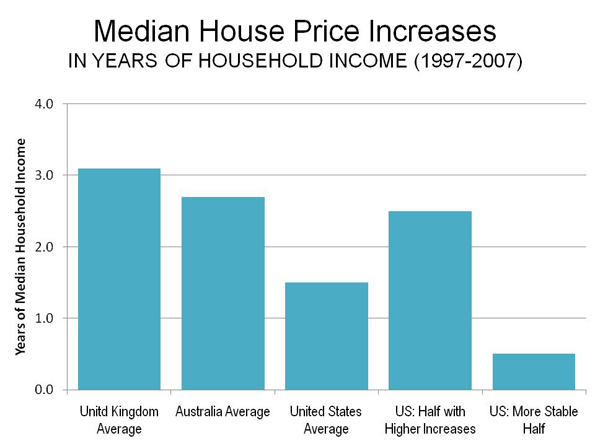

Missing the Housing Market Fundamentals: The housing market fundamentals were clear. With more liberal credit, the demand for owned housing increased markedly, virtually everywhere. In all markets of the United Kingdom and Australia, house prices rose so much that the historic relationship with household incomes was shattered. The same was true in some US markets, but not others (Figure 2).

On average, major housing markets in the United Kingdom experienced median house prices that increased the equivalent of three years of median household income in just 10 years (to 2007). The increases were pervasive; no major market experienced increases less than 2.5 years of income, while in the London area, prices rose by 4 years of household income. In Australia, house prices increased the equivalent of 3.3 years of income. Like the UK, the increases were pervasive. All major markets had increases more than double household incomes.

Based upon national averages, the inflating bubble appears to have been similar, though a bit more muted in the United States, with an average house price increase equal to 1.5 years of household income. But the United States was a two-speed market, one-half of which experienced significant house price increases and the other half which did not. In the price escalating half, house prices increased an average of 2.4 times incomes. The largest increases occurred in Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego, where house prices rose the equivalent of 5 years income. In the other half of the market, house prices remained within or near historic norms relative to incomes. A similar contrast is evident in Canadian markets. In some, house prices reached stratospheric and unprecedented highs, while in others, historic norms were maintained.

Underlying Demand: Greater Where Prices Rose Less: The difference between the two halves of the market was not underlying demand. Overall, the half of the markets with more stable house prices indicated higher underlying demand than the half with greater price escalation. Overall, the housing markets with higher cost escalation lost more than 2.5 million domestic migrants from 2000 to 2007, while the more stable markets gained more than 1,000,000 (Calculated from US Bureau of the Census data).

The Difference: Land Use Regulation: The primary reason for the differing house price increases in US markets was land use regulation, points that have been made by Krugman and Sowell. This is consistent with a policy analysis by the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, which indicated that the higher demand from more liberal credit could either manifest itself either in house price increases or in construction of new housing. Virtually all of the markets with the largest housing bubbles had more restrictive land use regulation.

These regulations, such as urban growth boundaries, building moratoria and other measures that ration land and raise its price collaborated to make it impossible for such markets to accommodate the increased demand without experiencing huge price increases (these strategies are often referred to as “smart growth”). In the other markets, less restrictive land use regulations allowed building new housing on competitively priced land and kept house prices under control. The resulting price distortions leads to greater speculation, as has been shown by economists Edward Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko.

A Wheel Disengaged from the Rudder: The normal policy response of interest rate revisions had little potential impact on the price escalating half of the housing market, because of the impact of restrictive state, metropolitan and local housing regulations. These regulations materially prohibited building on perfectly suitable land and thus drove the price up on land where building was permitted. So, while Greenspan and the Fed saw the “froth” in local markets, they missed its cause. The British Academy letter to the Queen is similarly near-sighted. Restrictive land use regulation has left central bankers in a position like a ship’s captain trying to steer a massive vessel with a wheel that is no longer connected to the rudder

The Bubble Bursts: When teaser mortgage rates expired and other interest rates reset, a flood of foreclosures occurred, which led to house price declines that negated much of the housing bubble price increases in the United States. The most significant of these took place in restrictive markets, especially in California and Florida. By September of 2008, the average house had lost nearly $100,000 of its value in the more restrictively regulated half of the market, and averaged $175,000 in these “ground zero” markets. These losses were unprecedented and far beyond the ability of mortgage holders to sustain. This led to “Meltdown Monday,” when Lehman Brothers collapsed and the Great Recession ensued.

By comparison, the losses in the more stable half of the market were modest, averaging approximately one-tenth that of the price escalating half.

Can We Avoid Another Bubble? The experience of the Great Recession underscores the importance of having a Fed and other central banks that not only pay attention, but also understand. This requires “getting their hands dirty” by looking beyond macro-economic aggregates and national averages.

This does not require an increasing of authority of the Federal Reserve or other central banks. As Donald L. Luskin suggested in The Wall Street Journal, we “don’t want the Fed controlling asset prices.” All we really need is for the Fed and other central banks to notice and understand what is going on, not only in housing, but in other markets as well.

A public that depends upon central banks to minimize the effect of downturns deserves institutions that are not only paying attention, but also understand what is driving the market. The Fed should use its bully pulpit, both privately and publicly, to warn state and local governments of the peril to which their regulatory policies imperil the economy.

There are strong indications that future housing bubbles could be in the offing. Not more than a year ago, the state of California enacted even stronger land use legislation (Senate Bill 375), which can only heighten the potential for another California-led housing bust in the years to come, while reducing housing affordability in the short run. There is a strong push by interest groups in Washington to go even further (see the Moving Cooler report), making it nearly impossible for housing to be built on most urban fringe land. This is a prescription for another bubble, this time one that would include the entire country, not just parts of it.

Note: Quarterly data has been available since 1952 from the Federal Reserve Board Flow of Funds accounts

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

The spread was initially zoned and approved for 1160 home sites but Halpin decided to turn what he called Indian Springs Ranch into a hybrid of private land ownership and common space sharing. Owners would hold title to a specific portion of the overall ranch – their homestead – and have access to the rest, much like a country club.

The spread was initially zoned and approved for 1160 home sites but Halpin decided to turn what he called Indian Springs Ranch into a hybrid of private land ownership and common space sharing. Owners would hold title to a specific portion of the overall ranch – their homestead – and have access to the rest, much like a country club.  Prominent people bought early sites: Connie Stevens, the actress; Carol and Robin Farkus, he the N.Y.C. Chairman of Alexanders Department Stores, Tom Bolger, chairman of Bell Atlantic. Buyers came from California, New York, the Midwest, the Minneapolis region. They attracted other well-heeled people, which helped sell out the homesites.

Prominent people bought early sites: Connie Stevens, the actress; Carol and Robin Farkus, he the N.Y.C. Chairman of Alexanders Department Stores, Tom Bolger, chairman of Bell Atlantic. Buyers came from California, New York, the Midwest, the Minneapolis region. They attracted other well-heeled people, which helped sell out the homesites.  Cornerstone was once a plain Jane hunting ranch owned by Texans. It was foreclosed and sold at auction to a local investor. Corson literally spotted the site for his employer, Dallas oilman Ray Hunt, off a dirt road. After two years of working with local officials on the development plan, construction began in 2004. The property opened in 2006. Homesteads range from one to one hundred acres, starting prices at $175,000 to seven figures plus an $80,000 club initiation fee and $6,000 a year dues, which are fairly typical.

Cornerstone was once a plain Jane hunting ranch owned by Texans. It was foreclosed and sold at auction to a local investor. Corson literally spotted the site for his employer, Dallas oilman Ray Hunt, off a dirt road. After two years of working with local officials on the development plan, construction began in 2004. The property opened in 2006. Homesteads range from one to one hundred acres, starting prices at $175,000 to seven figures plus an $80,000 club initiation fee and $6,000 a year dues, which are fairly typical.