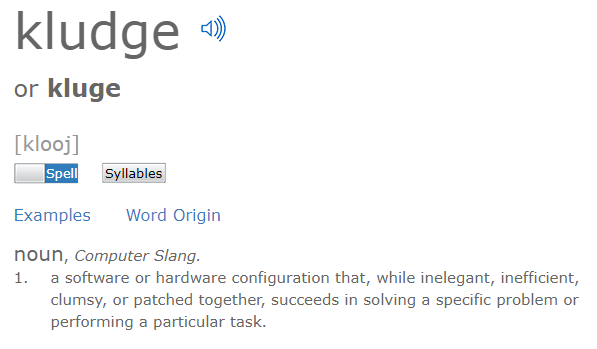

The quirks of software and operating systems that we seem to experience on a daily basis are the result of Kluges – almost all software is written with fixes that work for a particular problem, often without knowing exactly why that fix works. As both a land planner and developer of high level precision design and engineering software, I do not allow kluged fixes – for either business.

Why do kluges exist?

Kluges are rampant in software and hardware development.

A kluge is a quick and easy fix to one problem, but hardware and software design is very complex, so what might fix one problem can have dramatic negative effects elsewhere. The potential of a larger problem occurring with a kluged fix is very real, and everyone suffers because what ‘seems to work’ on a particular problem may have a domino effect for things that could not be foreseen in normal testing.

What other industry has rampant kluges?

Subdividing land!

Kluge #1: A new subdivision is more than likely designed by the local civil engineer who is unlikely to possess a strong neighborhood design background. This is because the firm who plans the development will also get the lucrative engineering and surveying work. For that reason, every engineering firm, and most land surveying firms boast of their land planning abilities, even if there are no qualified and experienced ‘neighborhood’ designers on staff.

Kluge #2: Assuming the local consultants relationship with the staff, council, and planning commission will result in a better development for the developer and builder – and a better city. The local consultant will likely have a familiarity with the people involved in the approval process, but may be far too easy compliant with every demand and change – no matter how absurd, than to argue a valid point with the city. They may know the design or idea is superior to the same old way things are done, but will try to convince the developer (who is paying for their services) the good idea is a bad idea. Progress stagnates – and this a major reason many new subdivisions looks the same (or worse) than one designed in the 1960’s.

Kluge #3: The cities’ regulations. Cities have in-house staff or hire outside consultants to maintain and update their regulations which are essentially a boiler-plate document of the adjacent city. Nothing in the regulations reward developers for doing a better job. Will the development be an asset or an instant slum? If it meets the minimums – it must be approved! That’s it.

Smart Code? There is nothing smart about this dumb idea – it only guarantees the consultant pushing these incredibly complex and restrictive codes is forever retained to consult at every city meeting. Overly restrictive code guarantees mindless replication and places a roadblock to progress and innovation.

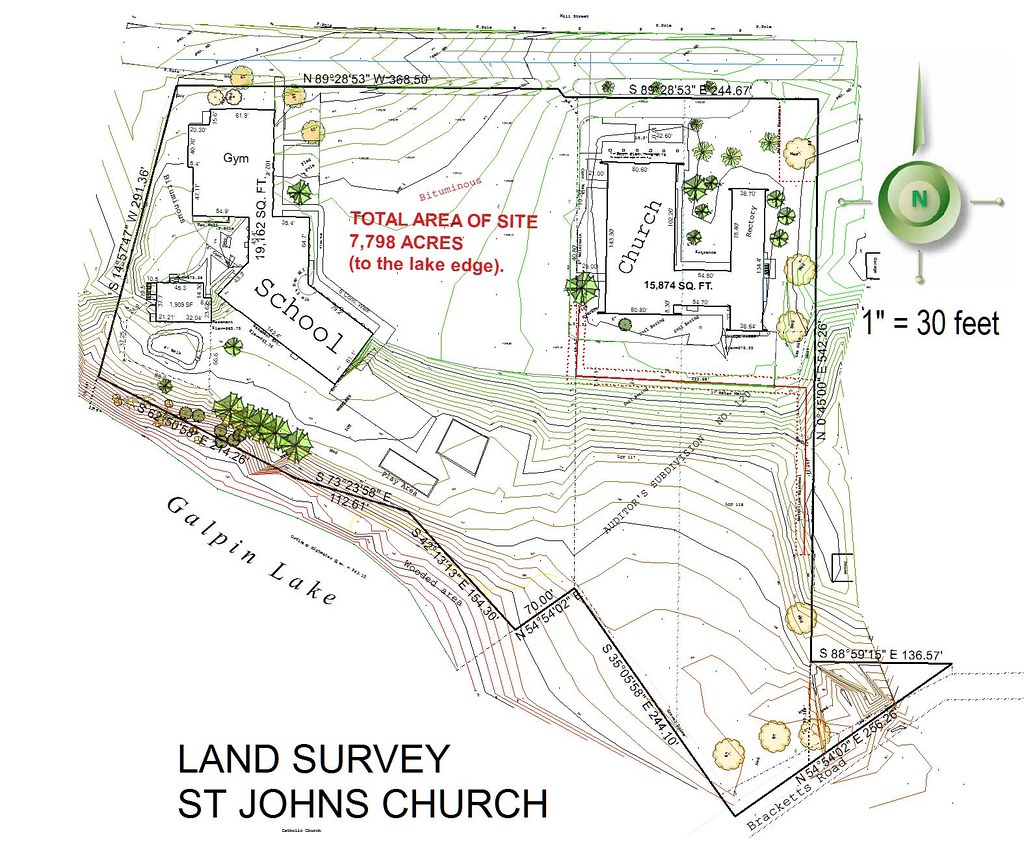

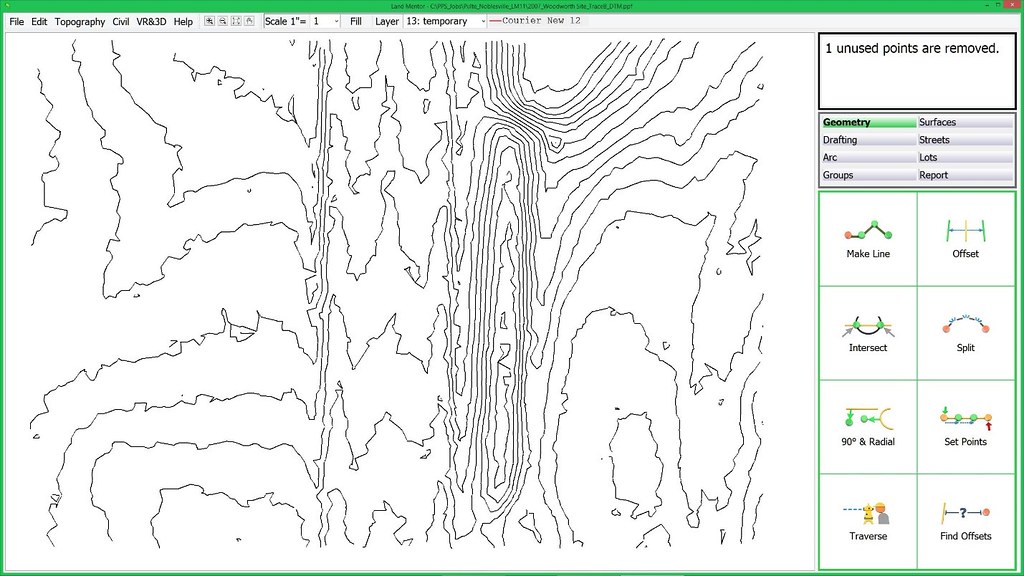

Kluge# 4: Technology used to develop land. I’ve been developing and marketing civil engineering, surveying, and design software for almost four decades. On a sales call – what do you think is the first question? How much faster can we get our work out? What’s the question I’ve never heard? How much better can we design our neighborhoods for our clients and those that will live within? The billions of dollars spent on CAD and GIS technology, training, updates, hardware, and support has resulted in zero difference in the actual pattern of growth! City planning commissions and councils are presented the same 2D plans that nobody can understand and visualize. Virtually unchanged since 1960, but presented in PowerPoint instead of transparency slides on an overhead projector.

Kluge #5: The land development consulting industry itself. I know of no other industry where the main design professionals (architects, planners, engineers, surveyors, etc.) are less likely to collaborate and communicate to assure the end user (the resident or business owner) is best served. There are many reasons why this is such a dysfunctional industry. The professionals involved have completely different skillsets. They often conflict with the others’ skillsets. All this can be solved with a new era of consulting industry where all involved have a common knowledge base to begin with – somewhat like the medical industry. This leads us to the next kluge…

Kluge #6: The universities only teach a narrow focus on an isolated aspect of the development process. With a ‘common knowledge base’ where a student will learn all aspects with technology and systems that can advance the industry we can tear down the barriers of communication and build collaboration. One major problem: the professors. They will need to harness better technologies and re-learn themselves – making an effort and need to communicate and collaborate among themselves.

Kluge #7: What happened to teaching – design? The world has morphed down to only a few major players in the software industry who have done nothing to advance the growth and redevelopment process through research and innovation. Over generations, gradually the world loses skillsets that were commonplace before computers existed. This is why all those new apartment projects and commercial buildings look the same, and that new subdivision is more mundane and cookie-cutter than in the past.

Kluge #8: Traffic regulations and trendy roundabouts. Don’t even try to convince me that roundabouts are a good idea, they are not. Of the well over 1,000 neighborhoods I’ve designed this past 26 years I’ve included a total of 3 roundabouts. There are much better alternatives that are safer and maintain flow, reducing time and energy while increasing safety.

Have you ever passed a restaurant thinking you are a bit hungry, but then decide to pass it up because you are routed a ridiculously long distance of multiple intersections to the place and instead pass it by? We all have. Instead of making access more efficient and convenient, often these rules do quite the opposite. As a pedestrian or on your bike have you ever tried to cross at a roundabout? Did you feel safer than at a signalized intersection? Progress? No. Kluge? Yes. Thus roundabouts are safer for pedestrians because most go far out of their way to avoid crossing them!

Kluge #9: Streets as the pedestrian route. Subdividing land is all about density – little about function. The pattern assures the most units (housing or commercial square footage) are sardined into a site. This pattern sets the street first – lots second. Nothing else. Pretty simple and quick with the latest technology (kluge #4). What of the streetscape (curb appeal, monotony)? What’s the views from within the home to adjacent open space? What open space? How easy is it to walk through the neighborhood to destinations you would want to walk or ride a bike to? Walks that simply follow the internal streets are highly unlikely to make a stroll convenient, thus the mindless walks designed automatically in CAD will discourage a stroll. To fix this deficiency, the vehicular and the pedestrian routes should be two different systems, merging where it makes sense.

Kluge #10: Revisions along the approval process. Suppose, an experienced and talented land planner carefully thought through the design of the neighborhood. The traffic entering maintains flow along streets void of monotony. There is a separate and connective pedestrian system, and the site plan follows the natural terrain honoring natures design, while reducing run-off and earthwork – which in turn saves the trees. At the first public meeting, the neighbors complain about traffic and the city planner demands you not connect at the proposed locations and add some new connections. You make small changes and as a result your traffic no longer flows as the planner designed. The engineer simply complies (see kluge #2). The length of the cul-de-sac is 70 feet longer than allowed, and will need to be adjusted, but that destroys the placement on top of a knoll which makes more sense, and the main trail connecting through the cul-de-sac is rerouted which destroys the pedestrian connectivity.

As a software developer and president of my company I do not allow kluges. The LandMentor system we developed has taken 12 years, mostly because it’s kluge free. I seriously doubt there is any software of any type that exists that has a 12 year initial development process. What we learned from the software business applies to land development and home design (single family and multifamily) – when problems arise or revisions are demanded, it’s most often better to start afresh than force an older ‘invested’ idea to work, the very definition of a kluge.

There is no quick fix to sustainable development, and no place for kluges.

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and Neighborhood Innovations, LLC. He is author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable and creator of LandMentor. His websites are rhsdplanning.com and LandMentor.com

Photo: Zoedovemany (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons