This is part one of a two-part series. Read part two here.

Striking a pose of defiance, contemporary urbanists see themselves as the last champions of happiness in a world plunged into quiet despair, and Canadian writer and journalist Charles Montgomery is no exception. Drawing on the emerging ‘science of happiness’, his new book Happy City, subtitled ‘transforming our lives through urban design’, joins a wave of anti-suburban literature spurred on by climate fears and the financial crisis. ‘As a system’, writes Montgomery, the dispersed city ‘has begun to endanger both the health of the planet and the well-being of our descendants.’

Happy are the poor

Repeating the fashionable wisdom, he says ‘cities must be regarded as more than engines of wealth; they must be viewed as systems that should be shaped to improve human well-being.’ Soon enough it’s apparent that to this way of thinking, well-being and poverty are by no means incompatible. ‘If a poor and broken city such as Bogota can be reconfigured to produce more joy’, he writes, ‘then surely it’s possible to apply happy city principles to the wounds of wealthy places.’

Montgomery starts off with ‘the happiness paradox’, arguing that ‘if one was to judge by sheer wealth, the last half century should have been a happy time for people in the United States and other rich nations … More people than ever got to live the dream of having their own detached home … The stock of cars far surpassed the number of humans who used them’. But, he is eager to explain, ‘the boom decades of the late twentieth century were not accompanied by a boom of happiness.’

For evidence, he refers to ‘surveys’ showing that ‘people’s assessment of their own well-being’ had ‘flatlined’, and cites a few others reporting rising rates of mental conditions related to depression. None of these inculpate suburban affluence, however, or suggest people yearn to turn the clock back to before they acquired it. And nor does he explore the problems surrounding measurement of these trends.

Moreover, such direct evidence as exists points in the opposite direction. A Pew Research Center survey, for example, found that far higher percentages of suburbanites than inner-city dwellers rated their communities as ‘excellent’ (Montgomery does concede that ‘residents in America’s central cities report being even less satisfied and even less socially connected than people in suburbia’, but does his best to explain it away).

The book openly admits that the idea of a link between unhappiness in the affluent west and urban form came from the rhetoric of Enrique Penalosa, former mayor of ‘poor and broken’ Bogota. Mr Penalosa declares that the unhappiest cities are not ‘the seething metropolises of Africa or South America’, but places like Atlanta, Phoenix and Miami in the US, ‘the most miserable cities of all’. Montgomery acknowledges this ‘is not science’, and ‘does not constitute proof’, but still sets out to show that ‘the decades-long expansion in the American [and Australian] economy’ and sagging levels of mental well-being aren’t just simultaneous developments, but connected, especially on the plane of ‘migration … from cities to the in-between world of sprawl.’

Suburban Straw Man

Before such a connection is anywhere near proven, though, Montgomery rushes in to assume it exists. Early in the first chapter, he is already asking ‘everything … would suggest that this suburban boom was good for happiness. Why didn’t it work?’ The habit of asserting yet-to-be or never-to-be established conclusions is commonplace throughout the book, and shapes the structure of his argument. Opening chapters set the scene with a case study of outer-suburban life which turns out to be a terrestrial version of Dante’s inferno.

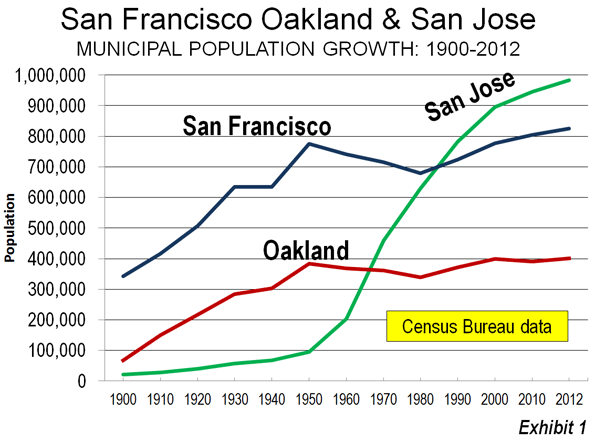

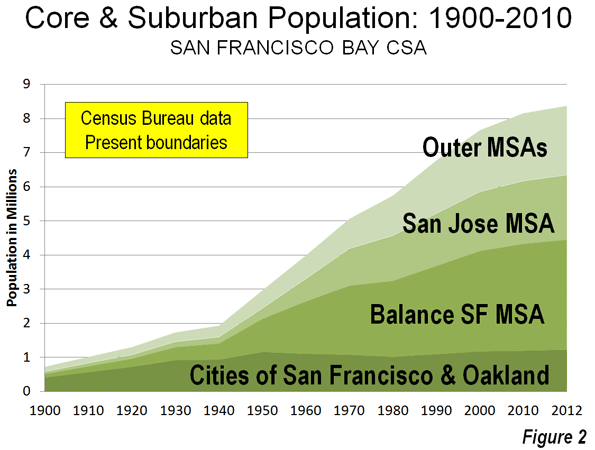

We’re introduced to the hapless Randy Straussner, a ‘super-commuter’ who drives 4 hours each workday on a round trip between his home in exurban Mountain House, California and his job 60 miles away in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most days he hits the road at 4:15 am to avoid the rush, putting off breakfast until he gets to work, and makes it back home at around 7:30 pm if ‘he was lucky.’ We’re told Randy won’t drink coffee or listen to talk radio, since ‘those just made him angry’ and aggravated ‘the pressures of the freeway.’ On arriving home, he would sometimes ‘grab a hose and water the garden until he calmed down’. Often he would hop ‘onto the elliptical trainer to straighten out his aching back’. When ‘the drive calcified his fatigue and frustration’, he drove to the gym where he could ‘sweat out his aggression.’

Further, Randy ‘did not know, like or particularly trust his neighbours’ who ‘didn’t get to know one another’, so ‘he disliked his neighbourhood intensely.’ Montgomery adds that Randy felt ‘his own family paid the price for his stretched life’. His first marriage failed and his son ‘slid off the rails’, ending up in the county jail.

Assuming this accurately accounts for Randy’s circumstances, just how representative is he of the typical outer-suburbanite? Peter Gordon, an urban economist at the University of Southern California, refers to empirical studies showing that ‘dispersed spatial structure was associated with shorter commute times’, suggesting “many individual households and firms ‘co-locate’ to reduce commute time [which] can be more easily [done] in dispersed metropolitan space …’

This is borne out by the surprising stability of commute times over extended periods. According to the US Nationwide Household Travel Survey, explains Gordon, the average metropolitan commute time was 25 minutes 2009, just one minute more than in 2001, despite relevant population growth of 12 per cent. The averages for sub-area types described as ‘suburban’ and ‘second city’ were actually lower than for the ‘urban’ or core sub-area. Analysing the INRIX Traffic Congestion Scorecard and urban density data, demographer Wendell Cox also finds support for links between higher population densities and longer commute times.

What about Randy’s other travails, are most suburbanites so estranged from their neighbours? A study cited by geographer Joel Kotkin found that for every 10 per cent drop in population density, the likelihood of people talking to their neighbours once a week rose 10 per cent. What about marital failure? Writing in the mid-2000s, Sue Shellenberger noted that ‘couples from central cities are 9 per cent more likely to crash and burn than couples from the suburbs, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.’ How about the prospect of winding up behind bars? On the basis of Brookings Institution research, Kotkin and Cox say suburban areas generally have substantially lower crime rates than ‘core cities.’

(With their painstaking attention to statistics, Kotkin and Cox are the bêtes noires of pro-density urbanists, who tend to fall back on anecdotal evidence).

‘The masses will still need suburbia’

Use of Randy Straussner’s plight to discredit life on the urban fringe constitutes a classic Straw Man fallacy.

From there, Montgomery proceeds to zig-zag between the fictional extremes of super-commuting hell and an opposite notion of high-rise ‘verticalism’, which he claims to reject. This dialectical type of approach has the advantage of inoculating him against the charge of ignoring inconvenient facts. In coming out for ‘a hybrid, somewhere between the vertical and horizontal city’, he gets to concede many pro-suburban realities, while clinging to his firmly anti-suburban conclusions.

Concessions to suburbia on job location, home ownership and affordability, the popularity of driving, and economic dynamism are scattered throughout the book, intermixed with the general tone of disapproval.

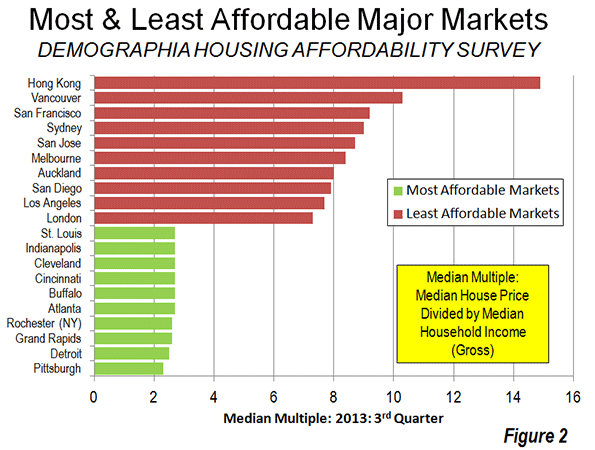

After many pages railing against ‘super-commuting’ and ‘detached houses with modest lawns … far from employment’, for instance, Montgomery is ready to admit that: ‘the US population is projected to grow by 120 million by 2050. Where will those people live? Downtowns and first-ring, streetcar-style suburbs will be able to accommodate only a fraction of the new demographic tidal wave. Most jobs have already moved out beyond city limits anyway.’ Then, quoting, he writes ‘the masses will still need suburbia.’

This is noteworthy, since other green urbanists hold fast to the myth that jobs are concentrated in the urban core. Data in the 2011 American Community survey suggests that the ‘job-housing balance’, measuring the number of jobs per resident employee in a geographic area, is ‘nearing parity’ in suburban areas of US metropolitan regions with more than a million people. This isn’t dramatically different from the position in Australia’s 6 major cities, which have some of the world’s most dispersed patterns of employment (and will share an estimated 20 million more people by 2050). It’s all consistent with Gordon’s co-location thesis.

In one chapter, Montgomery applauds his home town of Vancouver, which ‘has spent the past thirty years drawing people into density in a way that radically reversed a half century of suburban retreat.’ But he is forced to admit that ‘in 2012 Vancouver won the dubious honour of becoming the most expensive city for housing in North America. This means many people who work in the city … can’t afford to live there … ‘

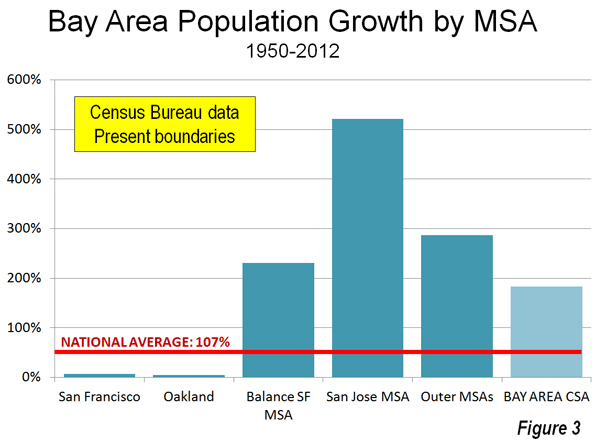

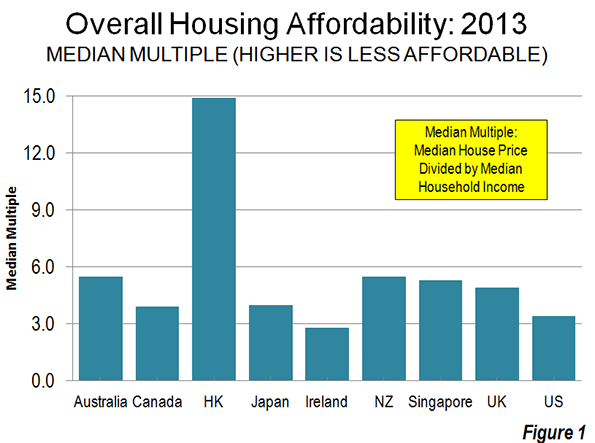

More generally, he says ‘the forces of supply and demand have helped make housing in some of the world’s most liveable cities’ – for which read dense cities – ‘the least affordable.’ Again: ‘as the wealthy recolonize downtowns and inner suburbs, and property values rise accordingly, millions of people are simply being excluded.’ (Always dialectical, Montgomery mostly heaps praise on dense places like Vancouver and Portland, usually rated severely or seriously ‘unaffordable’ in the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, while singling out dispersed Atlanta for rebuke, despite a consistent rating of ‘affordable’.)

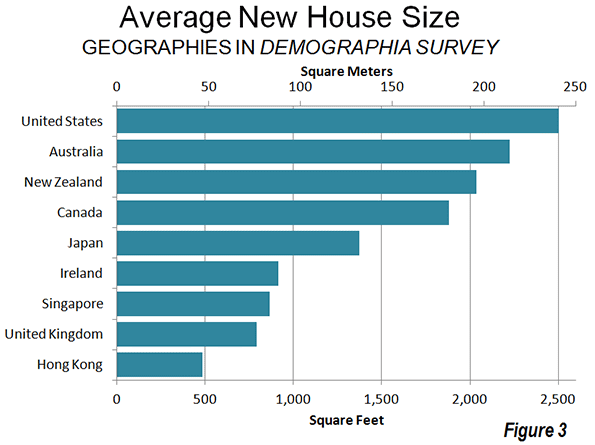

And noting the influence of Vancouver’s high-rise density, spawning the label ‘Vancouverism’, Montgomery feels compelled to mention that ‘people living in towers consistently reported feeling more lonely and less connected than people living in detached homes.’ Later he writes that ‘most of us also want to live in a detached home with plenty of privacy and space.’

On driving, the book is full of complaints that ‘governments have continued the decades-old practice of pouring tax dollars into highways … while spending a tiny fraction of that amount on urban rail and other transit service.’ Yet there is also the qualification that: ‘drivers experience plenty of emotional dividends. When the road is clear, driving your own car embodies the psychological state known as mastery: drivers report feeling much more in charge of their lives than transit users or even their own passengers.’ Montgomery lets slip the truth on popular preferences with the comment, ‘roads left to the open market – in other words, dominated by private cars.’

Accordingly, the American Community Survey reports that between 2007 and 2012, ‘driving alone’ increased as the dominant mode of commuting in the United States, rising from 76.1 to 76.3 per cent of work trips. This bears some relation to the co-location of suburban residents and businesses.

‘A marvellous thing’

Amidst his oscillations, Montgomery sketches an overview that reads like an encomium to the blessings of suburbia:

The rapid, uniform and seemingly endless replication of this dispersal system was, for many people and for many years, a marvellous thing. It helped fuel an age of unprecedented wealth. It created sustained demand for the cars, appliances and furniture that fuelled the North American [and Australian] manufacturing economy. It provided millions of jobs in construction and massive profits for land developers. It gave more people than ever before the chance to purchase their own homes on their own land, far from the noise and haste and pollution of downtown.

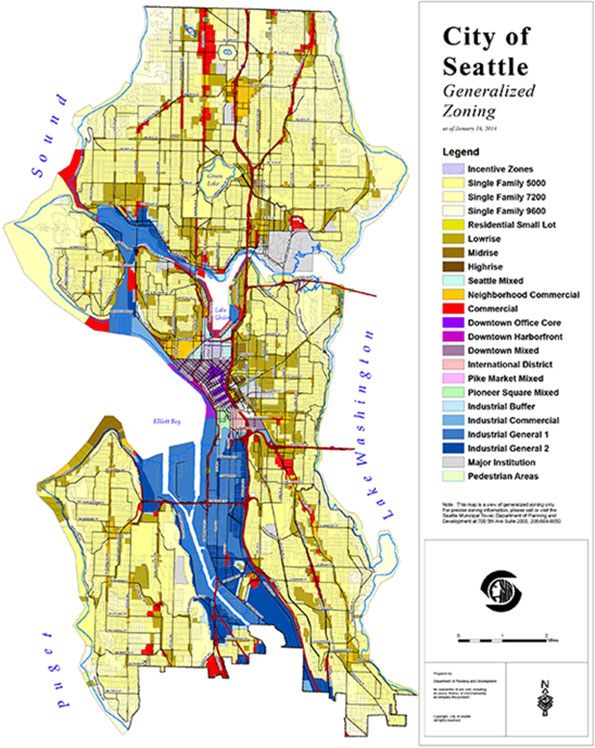

Having acknowledged the housing, transportation, employment and wider economic advantages of dispersion and suburbanisation, Montgomery could have come to the conclusion that they offer opportunities for a better life to millions of people, and should be embraced as a legitimate option by officials and planners. But that’s not where he ends up. Insisting that the dispersed city is now ‘inherently dangerous’, he signs on for pro-density ‘new urbanism’, calling for an overhaul of zoning codes, approval processes, infrastructure planning, tax incentives and funding practices to stimulate denser and less car-dependent redevelopment, aiming for transit-friendly, walkable, mixed-use, town centres and clusters of attached town-houses and low-rise apartments.

While ‘new urbanism’ sweeps aside the advantages of dispersion, Montgomery’s misconceived ideas show that it offers nothing better. Take housing affordability. At first he toys with the faddish notion of ‘a by-law stating that 15 per cent of dwellings in every new subdivision … must be suitable for people of low or moderate income’, a costly burden on new construction for developers and the majority of home buyers. As the Australian experience attests, this type of planning fails to offset the spike in land values which accompanies density.

Then, sensing this is far from enough, his demands escalate to the socialisation of housing supply: ‘it’s not enough to nudge the market towards equity … Governments must step in with subsidized social housing, rent controls, initiatives for housing co-operatives, or other policy measures.’ The destructive impacts of these sorts of measures on investment, market efficiency, public finances, and freedom of choice are passed over.

Later in the book, Montgomery discusses ways to draw developers into density and social housing, including changes to ‘infrastructure-funding rules, tax incentives and permit requirements.’ He contends that ‘if this sounds like a big fat bonus for property developers well it is … but the truth is, as long as we inhabit a capitalist system, the future of suburbia depends on them.’

It’s just that this isn’t capitalism as much as rent-seeking at the expense of consumers and other businesses, suppressing economic growth, opportunities and living standards. But that’s not a bad outcome for someone who extols the joys of poverty.

John Muscat is a co-editor of The New City, where this piece first appeared.

This is part one of a two-part series. Read part two here.