The “silver lining” in our five-years-and-running Great Recession, we’re told, is that Americans have finally taken heed of their betters and are finally rejecting the empty allure of suburban space and returning to the urban core.

“We’ve reached the limits of suburban development,” HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan declared in 2010. “People are beginning to vote with their feet and come back to the central cities.” Ed Glaeser’s Triumph of the City and Alan Ehrenhalt’s The Great Inversion—widely praised and accepted by the highest echelons of academia, press, business, and government—have advanced much the same claim, and just last week a report on jobs during the downturn garnered headlines like “City Centers in U.S. Gain Share of Jobs as Suburbs Lose.”

There’s just one problem with this narrative: none of it is true. A funny thing happened on the way to the long-trumpeted triumph of the city: the suburbs not only survived but have begun to regain their allure as Americans have continued aspiring to single-family homes.

Read the actual Brookings report that led to the “Suburbs Lose” headline: it shows that in 91 of America’s 100 biggest metro areas, the share of jobs located within three miles of downtown declined over the 2000s. Only Washington, D.C., saw significant growth.

To be sure, our ongoing Great Recession slowed the rate of outward expansion but it didn’t stop it—and it certainly didn’t lead to a jobs boom in the urban core.

“Absent policy changes as the economy starts to gain steam,” report author and urban booster Elizabeth Kneebone warned Bloomberg, “there’s every reason to believe that trend [of what she calls “jobs sprawl”] will continue.”

The Hate Affair With Suburbia

Suburbs have never been popular with the chattering classes, whose members tend to cluster in a handful of denser, urban communities—and who tend to assume that place shapes behavior, so that if others are pushed to live in these communities they will also behave in a more enlightened fashion, like the chatterers. This is a fallacy with a long pedigree in planning circles, going back to the housing projects of the 1940s, which were built in no small part on the evidently absurd, and eventually discredited, assumption that if the poor had the same sort of housing stock as the rich, they would behave in the same ways.

Today’s planning class has adopted what I call a retro-urbanist position, essentially identifying city life with the dense, highly centralized and transit-dependent form that emerged with the industrial revolution. When the city—a protean form that is always changing, and usually expands as it grows—takes a different form, they simply can’t see it as urban growth.

In his masterwork A Planet of Cities, NYU economist Solly Angel explains that virtually all major cities in the U.S. and the world grow outward and become less dense in the process. Suburbs are expanding relative to urban cores in every one of the world’s 28 megacities, including New York and Los Angeles. Far from a perversion of urbanism, Angel suggests, this is the process by which cities have grown since men first established them.

In the U.S., the hate affair with suburbs and single-family housing, even in the city, dates to their rapid growth in the American boom after the first World War. In 1921 historian and literary criticic Lewis Mumford described the expansion of New York’s outer boroughs as a “dissolute landscape,” “a no-man’s land which was neither town or country.” Decades later, Robert Caro described the new rows of small, mostly attached houses—still the heart of the city’s housing stock—built in the post-war years as “blossoming hideously” as New Yorkers fled venerable, and congested, parts of Brooklyn and Manhattan for more spacious, tree-lined streets farther east, south, and north.

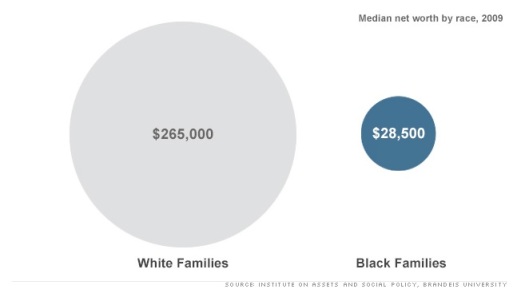

In the 1950s, the rise of mass-produced suburbs like Levittown, New York, and Lakewood, California, sparked even more extreme criticism. Not everyone benefited from the innovation that allowed the Levitts to pioneer homes costing on average just $8,000—African-Americans were excluded from the original development—but for many middle- and working-class American whites, the housing and suburban booms represented an enormous step forward. The new low-cost suburbia, wrote Robert Bruegmann in his compact history of sprawl, “provided the surest way to obtain some of the privacy, mobility and choice that once were available only to the wealthiest and most powerful members of society.”

The urban gentry and intelligentsia, though, disdained this voluntary migration. Perhaps the most bitter critic was the great urbanist Jane Jacobs. An aficionado of the old, highly diverse urban districts of Manhattan, Jacobs not only hated trendsetter Los Angeles but dismissed the bedroom communities of Queens and Staten Island with the memorable phrase, “The Great Blight of Dullness.” The 1960s social critic William Whyte, who, unlike Jacobs, at least bothered to study suburbs close up, denounced them as hopelessly conformist and stultifying. Like many later critics, he predicted in Fortune that people and companies would tire of them and return to the city core.

More recent critiques of suburbia have focused as well on their alleged vulnerability in an energy-constrained era. “The American way of life—which is now virtually synonymous with suburbia—can only run on reliable supplies of cheap oil and gas,” declares James Howard Kunstler in his 2005 peak oil jeremiad, The Long Emergency. “Even mild to moderate deviations in either price or supply will crush our economy and make the logistics of daily life impossible.”

Too often, the anti-surbanites seem to take a certain perverse comfort in any development, no matter how grim, that “helps” protect Americans from the “wrong choice” of aspiring to space of their own. The housing crash of 2007 was cheered on in some circles as the death knell of the suburban dream, as when theorist Chris Leinberger declared in the Atlantic that soon, poor families would be crowding into dilapidated McMansions in the “suburban wastelands.”

For retro-urbanists such as Richard Florida the reports, however premature, of the death of the suburbs, confirmed deeply held notions about the superiority of dense, urban living. He summarily declared the single-family house archaic, and the quest for homeownership one of the “countless forms of over-consumption that have a horribly distorting affect on the economy."

The Real Geography of America

But the simple fact remains that the single-family home has remained the American dream, with sales outpacing those of condominiums and co-ops despite the downturn.

Florida has suggested that simply stating the numbers makes me a sprawl lover While he and other urban nostalgists see the city only in its dense urban core, and the city’s role as intimately tied with the amenities that are supposed to attract the relatively wealthy members of the so-called “creative class,” I see the urban form as ever changing, and consider a city’s primary mission not aesthetic or simply economic but to serve the interests and aspirations of all of its residents.

Clearly the data supports a long-term preference for suburbs. Even as some core cities rebounded from the nadir of the 1970s, the suburban share of overall share of growth in America’s 51 major metropolitan areas (those with populations of at least one million) has accelerated—rising from 85 percent in the ’90s to 91 percent in the ’00s. There’s more than a tinge of elitism animating the urban theorists who think that urban destiny rides mostly with the remaining nine percent matters. Overall, over 70 percent of residents in the major metropolitan areas now live in suburbs.

Surveys, including those sponsored by the National Association of Realtors, suggest roughly 80 percent of Americans prefer a single family house to an apartment or a townhouse. Only 8 percent would prefer to live in an apartment. Yet just 70 percent of households live in a single-family house, while 17 percent live in apartments—suggesting the demand for single-family houses is still not being met. Such housing may be unaffordable, particularly in high-cost urban cores, but there is a fundamental market demand for it.

To be sure, the Great Recession did slow the growth of suburbs and particularly exurbs—but recent indicators suggest a resurgence. An analysis last October by Jed Kolko, chief economist at the real estate website Trulia, reports that between 2011 and 2012 less-dense-than-average ZIP codes grew at double the rate of more-dense-than-average ZIP codes in the 50 largest metropolitan areas. Americans, he wrote, “still love the suburbs.”

The Future Demographics of Suburbia

Ultimately the question of growth revolves around the preferences of consumers. Despite predictions that the rise of singles, an aging population and the changing preferences of millennials will create a glut of 22 million unwanted large-lot homes by 2025, it seems more likely that three critical groups will fuel demand for more suburban housing.

Between 2000 and 2011, there has been a net increase of 9.3 million in the foreign born population, largely from Asia and Latin America, with these newcomers accounting for about two out of every five new residents of the nation’s 51 largest metropolitan areas. And these immigrants show a growing preference for more “suburbanized” cities such as Nashville, Charlotte, Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth. An analysis of census data shows only New York—with nearly four times the population—drew (barely) more foreign-born arrivals over the past decade than sprawling Houston. Overwhelmingly suburban Riverside–San Bernardino expanded its immigrant population by nearly three times as many people as the much larger and denser Los Angeles–Orange County metropolitan area.

Clearly, immigrants aren’t looking for the density and crowding of Mexico City, Seoul, Shanghai, or Mumbai. Since 2000, about two-thirds of Hispanic household growth was in detached housing. The share of Asian arrivals in detached housing is up 20 percent over the same span. Nearly half of all Hispanics and Asians now live in single-family homes, even in traditionally urban places like New York City, according to the census’s American Community Survey.

Nowhere are these changes more marked than among Asians, who now make up the nation’s largest wave of new immigrants. Over the last decade, the Asian population in suburbs grew by about 2.8 million, or 53 percent, while that of core cities grew by 770,000, or 28 percent.

Aging boomers, too, continue to show a preference for space, despite the persistent urban legend that they will migrate back to the core city. Again, the numbers tell a very different story.

A National Association of Realtors survey last year of buyers over 65 found that the vast majority looked for suburban homes. Of the remaining seniors, only one in 10 looked for a place in the city—less than the share that wanted a rural home. When demographer Wendell Cox examined the cohort that was 54 to 65 in 2000 to see where they were a decade later, the share that lived in the suburbs was stable, while many had left the city—the real growth was people moving to the countryside. Within metropolitan areas, more than 99 percent of the increase in population among people aged 65 and over between 2000 and 2010 was in low-density counties with less than 2,500 people per square mile.

With the over-65 population expected to double by 2050, making it by far America’s fastest-growing age group, they appear poised to be a significant source of demand for suburban housing.

But arguably the most critical element to future housing demand is the rising millennial generation. It has been widely asserted by retro-urbanists that young people prefer urban living. Urban theorists such as Peter Katz have maintained that millennials (the generation born after 1983) have little interest in “returning to the cul-de-sacs of their teenage years.”

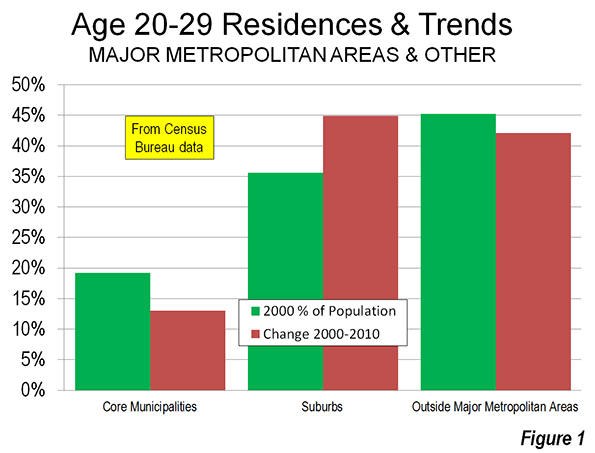

To bolster their assertions, retro-urbanist point to stated-preference research showing that more than three quarters of millennials say they “want to live in urban cores.” But looking at where millenials actually live now—and where they see themselves living in the future—shows a very different story. In the nation’s major metropolitan areas, only 8 percent of residents aged 20 to 24 (the only millennial adult age group for which census data is available) live in the highest-density counties—and that share has declined from a decade earlier. What’s more, 43 percent of millenials describe the suburbs as their “ideal place to live”—a greater share than their older peers—and 82 percent of adult millenials say it’s “important” to them to have an opportunity to own their home.

And, of course, as people get older and take on commitments and start families, they tend to look for more settled, and less dense, environments. A 2009 Pew study found that 45 percent of Americans 18 to 34 would like to live in New York City, compared with just 14 percent of those over 35. As about 7 million more millenials—a group the Pew surveys show desire children and place a premium on being good parents—hit their 30s by 2020, expect their remaining attachment to the city to wane.

This family connection has always eluded the retro-urbanists. “Suburbs,” Jane Jacobs once wrote, “must be difficult places to raise children.” Yet suburbs have served for three generation now as the nation’s nurseries. Jacobs’s treatment of the old core city—particularly her Greenwich Village in the early 1960s—lovingly portrayed these places as they once were, characterized by class, age, and some ethnic diversity along with strong parental networks, often based on ethnic solidarity.

To say the least, this is not what characterizes Greenwich Village or in Manhattan today. In fact, many of the most vibrant, and high-priced urban cores—including Manhattan, San Francisco, Chicago, and Seattle—have remarkably few children living there. Certainly, the the 300-square-foot “micro-units” now all the rage among the retro-urbanist set seem unlikely to attract more families, or even married couples.

The Persistence of the Suburban Economy

As Americans have voted with their feet for the suburbs, employers have followed.

Despite the attention heaped on a handful of companies like United Airlines and Quicken Loans that have moved “back to the city,” the suburbanization of the overall American economy has continued apace. Historically, suburbs served largely as residential areas, so-called bedroom communities, but their share of steadily.

Job dispersion is now a reality in virtually every metropolitan area, with twice as many jobs located 10 miles from city centers as in those centers. Between 1998 and 2006, as 95 out of 98 metro areas saw a decrease in the share of jobs located within three miles of downtown, according to a Brookings report. The outermost parts of these metro areas saw employment increase by 17 percent, compared to a gain of less than 1 percent in the urban core. Overall, the report found, only 21 percent of employees in the top 98 metros in America live within three miles of the center of their city.

This decentralization of jobs was slowed somewhat by the Great Recession, which hit more dispersed industries like construction, manufacturing and retail particularly hard. Yet an analysis of jobs in 2010 by the Rudin Center for Transport Policy and Management found that dispersion had continued. Between 2002 and 2010 only two of the top 10 metropolitan regions (New York and San Francisco) saw a significant increase in employment in their urban core.

Some observers claim that job growth is coming to the urban core in response to the changing preferences of younger workers, particularly in high-tech fields and as much media attention has been given to a few prominent social media start ups in New York and San Francisco. Similar pronouncements were made during the great dot-com boom of the late 1990s, and burst along with the bubble. In fact, the number of urban core country tech jobs actually shrank over the past decade, according to an analysis of Science, Technology, Engineering and Management (STEM) jobs by Praxis Strategy Group.

While companies in walking distance of big-city reporters make news out of all proportion to their importance, virtually all the major tech concentrations in the country—including Silicon Valley—are suburban. San Jose is a postwar suburban core municipality, having experienced the vast bulk of its growth since 1940. Virtually all the nation’s top tech companies—Apple, Google, Hewlett-Packard, Intel, Oracle and even Facebook—are located in suburban settings 45 minutes or more from San Francisco. Apple’s recent plans to construct its new corporate campus in bucolic Cupertino elicited anger from the Environment Defense Fund and other smart-growth advocates, but reflects the fact that the vast majority of the tech industry is located, along with the bulk of its workforce, in the suburbs.

Apple employs many experienced engineers, many of whom have families and prefer to live in suburbs. In 2012 San Francisco had a significantly lower share of STEM jobs per capita than Santa Clara County. And the new rising stars of the tech world—Austin and Raleigh-Cary—are even more dispersed and car-dependent than San Jose.

What Really Matters

While they’ve weaved a compelling narrative, the numbers make it clear that the retro-urbanists only chance of prevailing is a disaster, say if the dynamics associated with the Great Recession—a rise in renting, declining home ownership and plunging birthrates—become our new, ongoing normal. Left to their own devices, Americans will continue to make the “wrong” choices about how to live.

And in the end, it boils down to where people choose to live. Despite the dystopian portrays of suburbs, suburbanites seem to win the argument over place and geography, with far higher percentages rating their communities as “excellent” compared to urban core dwellers.

Today’s suburban families, it should be stressed, are hardly replicas of 1950s normality; as Stephanie Coontz has noted, that period was itself an anomaly. But however they are constituted—as blended families, ones headed up by single parents or gay couples—they still tend to congregate in these kinds of dispersed cities, or in the suburban hinterlands of traditional cities. Ultimately life style, affordability and preference seem to trump social views when people decide where they would like to live.

We already see these preferences establishing themselves, again, among Generation X and even millennials as some move, according to The New York Times,toward “hipsturbia,” with former Brooklynites migrating to places along the Hudson River. The Times, as could be expected, drew a picture of hipsters “re-creating urban core life” in the suburbs. While it may be seems incomprehensible to the paper’s Manhattan-centric world view by moving out, these new suburbanites are opting not to re-create the high-density city but to leave it for single-family homes, lawns, good schools, and spacious environments—things rarely available in places such as Brooklyn except to the very wealthiest. Like the original settlers of places like Levittown, they migrated to suburbia from the urban core as they get married, start families and otherwise find themselves staked in life. In an insightful critique, the New York Observerskewered the pretensions of these new suburbanites, pointing out that “despite their tattoos and gluten-free baked goods and their farm-to-table restaurants, they are following in the exact same footsteps as their forebears.”

So, rather than the “back to the cities” movement that’s been heralded for decades but never arrived, we’ve gone “back to the future,” as people age and arrive in America and opt for updated versions of the same lifestyle that have drawn previous generations to the much detested yet still-thriving peripheries of the metropolis.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared in the The Daily Beast.

Suburbs photo by BigStock.