The prospect of falling car use now needs to be firmly factored into planning for western cities.

That may come as a bit of a surprise in light of the preoccupation with city plans that aim to get people out of their cars, but it is already happening. And it is highly likely to continue regardless of whether or not we promote urban consolidation and expensive transit systems.

But not necessarily lower resource consumption

Of course, as day-to-day travel savings are made by households these can simply result in other forms of consumption, offsetting any resource savings. This should not be surprising. Final demand embodies resources consumed right across the production and distribution chain. Savings from lower transport spending (including commuting) – an intermediate input in the chain – that lead to lower prices translate into increases in discretionary spending (assuming constant or rising incomes).

Hence, the reduction in resource use and pollution sought by subsidising public transport and promoting higher density living may simply be spent on resource-intensive appliances, recreation, entertainment, and inter-city and international travel.

Look to the fringe to look to the future

Putting that inconvenient equation aside, long-term plans for cities should avoid simply projecting past behaviours into the future. Instead, we might look to changes at the margin that signal the issues, discoveries, and events that might determine the long-term outcomes we are interested in.

So let’s look at what’s happening at the margins of car use, focusing for the purpose of illustration on Auckland.

First, travel demand

The New Zealand Travel Survey has been conducted since 2003. The results are published on a two-yearly rolling basis. Using Statistics New Zealand population estimates I have calculated annual “per person” measures for Auckland from 2003 to 2011. There are some sampling issues and qualifications regarding the survey that mean motor cycle and bicycle use statistics for Auckland are not considered reliable enough to use. Even given sampling error, the balance point to some significant and consistent shifts.

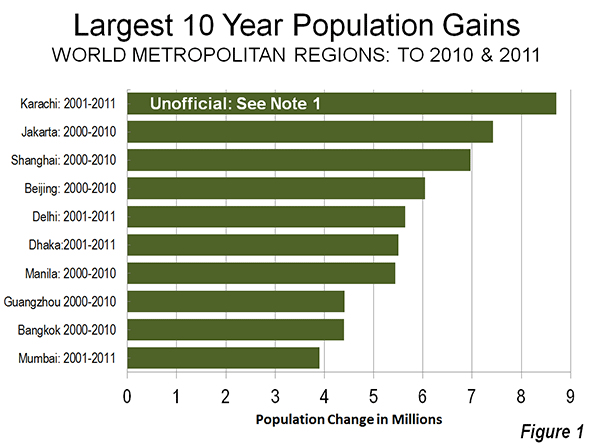

For example, total travel (measured as annual kilometres per resident) appears to have peaked around 2007 (Figure 1). In fact, recorded travel declined by 15% over the period. Public transport has done better, down 12% overall but actually increasing 13% between 2007 and 2011.

|

| Figure 1: Aucklanders’ Travel by Mode, 2003-2011 |

More telling, though, has been declining car use. The first column in Table 1 shows changes over the whole period. The second column shows changes between the 2007 travel peak and 2011.

The fall in car dependence since 2007 has been marked among passengers (-23%). Perhaps that means fewer discretionary trips are being taken. This and a 14% decline in driver kilometres and 17% fewer trip legs confirms what the vehicle counts say – cars are being driven significantly less in Auckland (particularly inner Auckland) now than they were five or ten years ago.

|

|

Period 2003-11

|

Peak

2007-11

|

|

Driver

|

||

|

Km

|

-4%

|

-14%

|

|

Hours

|

3%

|

-12%

|

|

Trip Legs

|

1%

|

-17%

|

|

Passenger

|

||

|

Km

|

-33%

|

-23%

|

|

Hours

|

-18%

|

-17%

|

|

Trip Legs

|

-8%

|

-22%

|

|

All Car Users

|

||

|

Km

|

-16%

|

-17%

|

|

Hours

|

-5%

|

-13%

|

|

Trip Legs

|

-3%

|

-19%

|

Possible reasons:

1. We know already that an ageing population reduces car use.

2. Public transport is playing a growing but so far minor role (up from 3.7% to 3.9% share of all kilometres travelled). An average 76km per person growth in public transport use since 2007 hardly offsets the 1,810km average contraction in distance travelled by car.

3. Lower real incomes and higher fuel prices play a part. A sharp contraction since 2007 suggests that economic conditions have an impact on motoring far more immediate and influential than trying to reshape the shape the city and how people live in it might.

4. The decentralisation of jobs, recreation and entertainment, professional services, and consumer services – including retailing – mean that people can get more done closer to where they live. Trying to turn this clock back by pushing commercial activity back into the central city and then providing subsidised public transport to access it seems somewhat obtuse in the light of this development.

Second, car purchases

The Ministry of Transport publishes new car registrations (which include imported used cars). It also provides data on the total vehicle fleet since 2000.

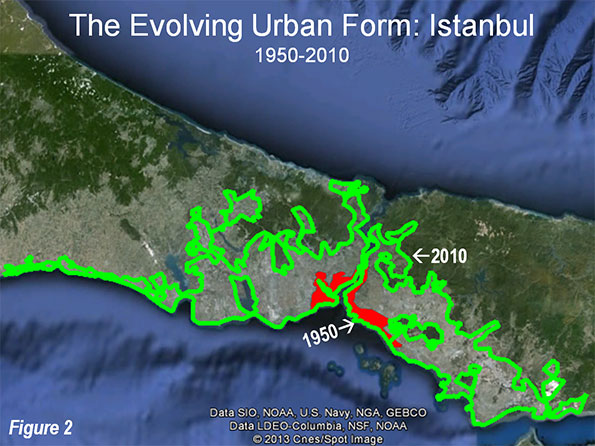

Long-term registration statistics are interesting when related to national population data (Figure 2). Apart from a hiccup in 1991 growth in registrations was more or less continuous from 1950 until 2003. Since then there has been a sharp decline. Time will tell whether this is cyclical or signals a long-term shift. It is noteable, though, that 2009, 2010, and 2011 figures fall well below trend.

|

| Figure 2: Trends in New Car Registrations |

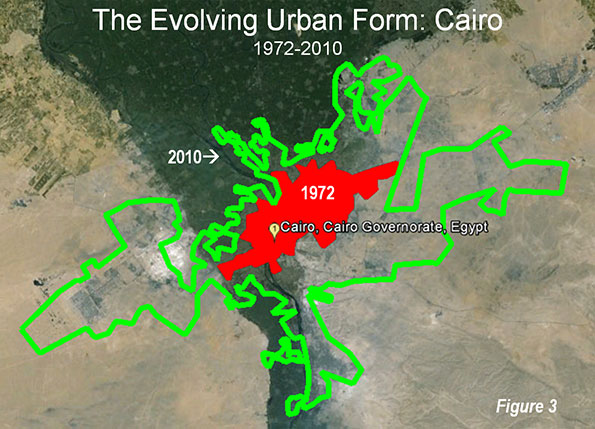

This slowdown in new car registrations is reflected in two ways. First, it is reflected in total fleet size, for which data are available from 2000 (Figure 3). This shows that 2007 was a turning point in total numbers, consistent with evidence that driving in Auckland peaked in that year. That’s presumably good for the environment.

|

| Figure 3: New Car Registrations, New Zealand 2000-2011, |

Second, with the slow-down in imports, the fleet has begun to age (Figure 4). That’s presumably bad for the environment, as older cars are less efficient and generate more emissions.

|

| Figure 4: New Zealand’s Ageing Car Fleet |

Third, fleet changes

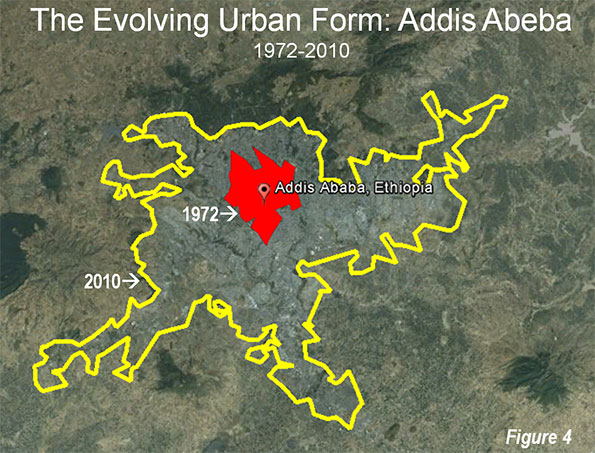

Fleet composition is changing as growth slows. The average CC rating of newly registered vehicles in 2000 was 2,127. This climbed to 2,191 in 2005, but fell to 2,033 in 2011, an 8% fall in six years.

If this is a sign of things to come an increase in the turnover of vehicles would boost fleet efficiency over the medium term even without taking account of the greater engine efficiencies being delivered and gains among electric and hybrid vehicles

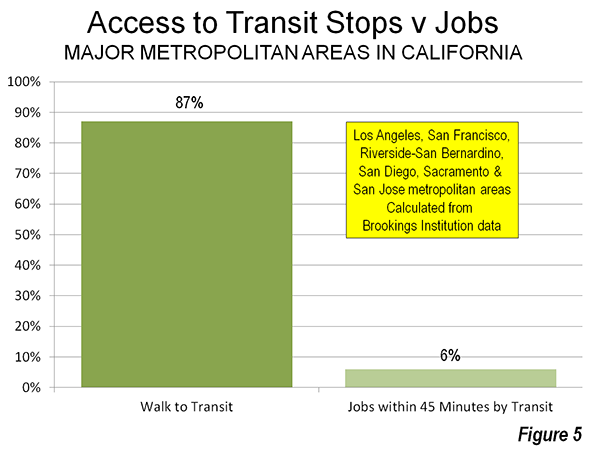

Add to that the prospect supported by these numbers of increasing differentiation among vehicle styles (Figure 5). At one end sits the large weekend recreational vehicle, perhaps falling as a share of new vehicles – or at least being down-sized. At the other is the increasingly popular city runabout or smart car, and in the middle the family sedan, the work horse with an engine size now likely to be well under 2,000cc.

|

| Figure 5: Changes in Engine Size of Newly Registered Vehicles, 2000-2011 |

So what does this all mean?

There is evidence accumulating to suggest that significant changes are taking place at the margin of transport demand and car dependence. If this is a sign of things to come it raises questions about long-term road expenditure, about dire predictions of road congestion, and about the benefits of adopting expensive land use and transport measures designed to force people out of their cars.

Already, within a more constrained economy, people seem to be making their own decisions to reduce car dependence.

In terms of city planning, it suggests that decentralisation may be more sustainable than the compact city protagonists make out. In this respect, is interesting that motorway traffic counts show that significant reductions in inner city vehicle flows are offset by gains (albeit much smaller) in outer parts of the city – even as measured distance travelled falls.

And Auckland definitely needs to rethink assumptions behind spending plans for major road and rail infrastructure – and confront the risks and costs of getting them wrong.

And, incidentally, it’s about time New Zealand’s Ministry for the Environment updated its report card on trends in the environmental impact of vehicle travel – which only goes up to 2007, a year which may prove to be a turning point in long-term travel behaviour.

Phil McDermott is a Director of CityScope Consultants in Auckland, New Zealand, and Adjunct Professor of Regional and Urban Development at Auckland University of Technology. He works in urban, economic and transport development throughout New Zealand and in Australia, Asia, and the Pacific. He was formerly Head of the School of Resource and Environmental Planning at Massey University and General Manager of the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation in Sydney. This piece originally appeared at is blog: Cities Matter.