If you’re an enviro-regulator with a mission, preventing “sprawl” has been ideologically trendy in recent decades. You have successfully predicated your argument on past-history soils-management technological inadequacy, it must be enormously threatening to look back and realize that technology has been gaining on you and is now capable (in engineering terms) and affordable (in end-user cost terms) of enabling just the sorts of rural development the majority of the market-for-housing wants, but you’ve been trying so hard to prevent: Currier-and-Ives-tradition large-lot houses in the countryside.

Case in point: the inadequate-soils argument long used by anti-rural-housing-and-business advocates to demand that buildings not be built anywhere soils aren’t naturally capable of environmentally-sound management of on-site sewage flows, and connection to a piped municipal sewer system isn’t feasible.

One way to win the sewage-flow argument is to control the information flow so that targets of your engineering-inadequacy argument don’t get to know about technologies they might employ, passing all tests of environmental quality and product affordability, to build and occupy the house and-or business in the countryside they want and you don’t want them to have.

If you’re good at it, you can keep the new technologies pretty much unknown to the public long after they’ve ceased being new. For example: chances are your local and regional planners and zoners never passed along to you the Winter 1996 issue of “Pipeline,” a quarterly effort of the National Small Flows Clearinghouse, a Federally-funded enterprise of the National Environmental Services Center within the U.S. Department of Agriculture and headquartered at West Virginia University. That issue was devoted almost entirely to a then-quite-innovative alternative to traditional septic-tank-and-disposal-field design: it was labeled “aerobic” to reflect its use of electric-powered air flows to enable oxygenated digestion, in contrast to the anaerobic design for traditional septic tanks.

As the text explains, “aerobic…a good option…where soil quality…isn’t.” The Aerobic Wastewater Treatment module can be installed and used irrespective of natural site conditions. That was 26 years ago. Last month, the State of Maryland adopted legislation to advance “Smart-Growth” and prevent rural development by establishing new and more rigorous criteria for septic (anaerobic) tank installations. Not a word in the press releases about aerobic technology. Irony: your tax dollars pay for “Pipeline,” which describes its objective as “small community wastewater issues explained to the public,” but in the last 26 years there’s been zero effort, on the part of your planners and zoners to assist in that effort. Have they actually worked to suppress such (in their opinion) non-useful information, possible counterpoints to their growth-control doctrines? You decide.

It was (and still is) understandable that land with low-permeability clay soils, high water tables, shallow depth to bedrock, and similar negative qualities would be disqualified for in-ground septic systems on the grounds of predictable system failure. If non-soil-based systems didn’t exist, the logic of rural-development-prevention (no access to municipal piped systems) would prevail. That’s why Denver, back in the 80s, mounted a regional green-belt anti-sprawl campaign by curtailing municipal system expansion into previously-unserved real estate. It’s not understandable that development controls based on soil (in)capabilities should still be in place long after non-soils-based technologies have been engineered, manufactured, and marketed. Unless, of course, the soil-capability argument was an excuse, not a real reason.

* * * * * *

Before these little AWT packages became available (and have been unsuccessfully publicized by the Feds since the 90s) the industry was already interested in an even lower-tech non-soils-based design: the evapo-transpiration concept, where primary-treated effluent coming from a traditional septic tank is released into an under-sealed heavily-vegetated patch (in some designs, a shallow lagoon) where about two feet of vertical evaporation will take place annually if rain and snow are kept off. That’s a typical number for northern New England.

Depending on location with respect to septic-tank discharge, electric power for pumping may or may not be needed. But industry interest was pretty much trumped by regulator hostility. Many fruitless meetings were held in Montpelier and Waterbury on the subject, even one at which copies of the 1980 Environmental Protection Agency Design Manual were handed around the table, to no avail.

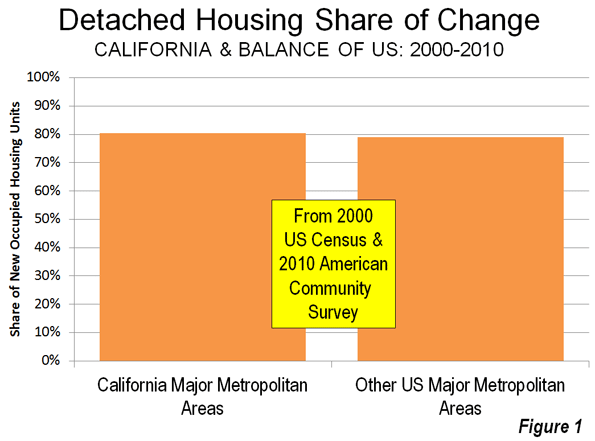

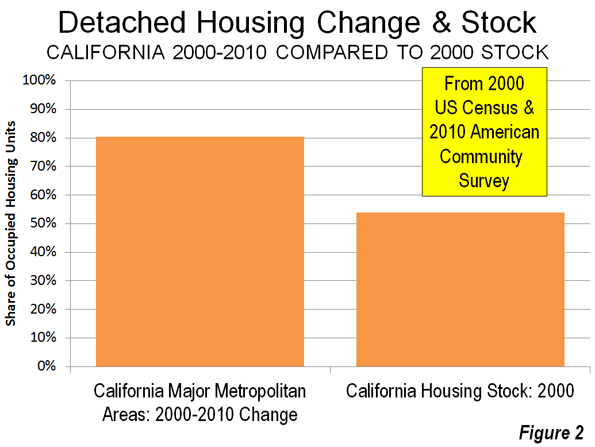

This raises the basic Smart-Growth question: can it be sold to (or forced on) a generally unwilling public only by pretending that the engineering basis for “sprawl” doesn’t work? There’s ample historical evidence –see Chapter 5, Ben Wattenberg’s “The First Measured Century”, for example—that “…the preference for the single-family detached house was even higher at the end of the 20th century than at the beginning…” but the top-down campaign against just such “sprawl” continues anyway.

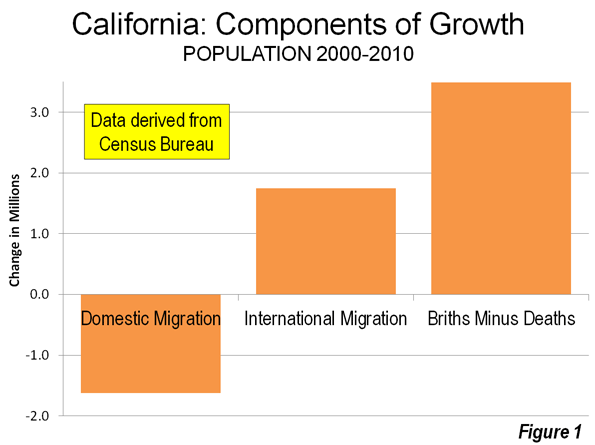

It doesn’t seem to matter that such exemplars of Smart-Growth as Portland, OR now show some of the highest housing costs in the nation; or that a new Cal State report on housing costs and young-adult out-migration speaks to a preference “…for raising children on backyards rather than condominium balconies.” One way to counter that, of course, would be to make the backyard even more expensive than the condo by pretending that the traditional on-site sewage system for the former is an engineering health hazard, and that no environmentally-acceptable customer-affordable alternates exist.

To advance Smart-Growth it helps to keep the research and publications of the National Small Flows Clearinghouse as hidden as possible. There are some things, you understand, that the natives are better off not knowing, lest it make them restless.

Martin Harris is a Princeton graduate in architecture and urban planning with a range of experience in fields ranging from urban renewal and air-industrial parks to the trajectory of small-town planning and zoning in States like Vermont.

Rural Vermont home photo by Bigstockphoto.com.