It’s a given in our representative system that policies adopted into law should have popular support. However, there is a distinction to be made between adopting a policy consistent with what a majority of people want, and pushing a policy while making dubious claims that it harnesses “the will of the people.”

The former is a valid exercise in democracy; the latter is a logical fallacy. Smart Growth advocates are among the most effective practitioners of Argumentum ad Populum, urging everyone to get on the bandwagon of higher densities, compact mixed-uses, and transit orientation because all the “cool cities” are doing it.

Smart Growth advocates also claim this is what people prefer, even if it is not how they currently live. The two core features of Smart Growth land use — high densities and multi-family dwellings — are simply not preferred by most Americans in most places, despite the trendy push for Livability, New Urbanism, Resilient Cities, Smart Codes, Traditional Neighborhood Design, Transit Oriented Developments or any other euphemistic, clever name currently in fashion.

In the internal data of the 2011 Community Preference Survey commissioned by the National Association of Realtors, no specific question was asked about density, but 52 percent of respondents said, if given a choice, they would prefer to live in traditional suburbs, small towns or the rural countryside. Another 28 percent chose a suburban setting that allowed for some mixed uses (Question 5). Taken together, this shows an overwhelming preference for low densities. Only 8 percent of the respondents favored a central city environment.

As for vibrant urbanism, only 7 percent were “very interested” in living in a place “at the center of it all.” Most people wanted to live “away from it all” (Question 17). An astonishing 87 percent said “privacy from neighbors” was important to them in deciding where to live. One can reasonably infer that a majority of this majority would favor low density places with separated uses rather than crowded, noisy mixed use locations that blur the line between public and private.

When presented with a range of housing choices, 80 percent preferred the “single-family detached house” (Question 6). Only eight percent chose an apartment or condominium. Furthermore, 61 percent preferred a place where “houses are built far apart on larger lots and you have to drive to get to schools, stores, and restaurants” over 37 percent who wanted a place where “houses are built close together on small lots and it is easy to walk to schools, stores and restaurants” (Question 8).

So — absent the loaded terms and buzzwords that are central to Smart Growth — a large majority of randomly selected people from across the country showed a strong preference for the land use pattern derisively referred to as “sprawl.”

Yet the press release from the National Association of Realtors proclaimed that “Americans prefer smart growth communities.” This is because on Question 13, respondents were given a description of two communities:

Community A, a subdivision of only single family homes with nothing around them. Not even sidewalks!

Community B: lots of amenities all “within a few blocks” of home. Of course, the description neglected to mention the population density and degree of residential stacking required to put all those dwellings in such close proximity to walkable retail. This was a significant omission, since the first housing option offered in Community B was “single family, detached,” on “various sized lots.”

Community B received 56 percent support.

So, with just one response to an unrealistic scenario, out of twenty answers that included many aversions to Smart Growth, the myth that people prefer Smart Growth was spread. The National League of Cities released a Municipal Action Guide to thousands of elected and appointed officials declaring the preference for Smart Growth, and the online network Planetizen, among others, uncritically helped spread the news.

Missing from the triumphalism was this important caveat in the 98-page analysis of the results by the consultants who conducted the survey:

“Ideally, most Americans would like to live in walkable communities where shops, restaurants, and local businesses are within an easy stroll from their homes and their jobs are a short commute away; as long as those communities can also provide privacy from neighbors and detached, single-family homes. If this ideal is not possible, most prioritize shorter commutes and single-family homes above other considerations.”

In addition to spinning the results of preference surveys, Smart Growthers also ignore them. Maryland is a case study in how to disregard what people want while claiming the opposite. In drafting a statewide growth management plan that anticipated “increased demand for housing, an aging population, and diverse communities,” Maryland officials ignored a robust 55+ Housing Preference Survey from Montgomery County that specifically addressed this concern.

The survey showed that most seniors planned to remain in their present homes upon retirement. Only 30 percent planned to move, and, of that group, only a small percentage would consider an apartment or condominium. This should have mattered to Maryland officials trying to gauge housing preferences for their senior population. Instead, the architects of PlanMaryland looked elsewhere to find studies that reinforced their assumptions.

The Great Conflation

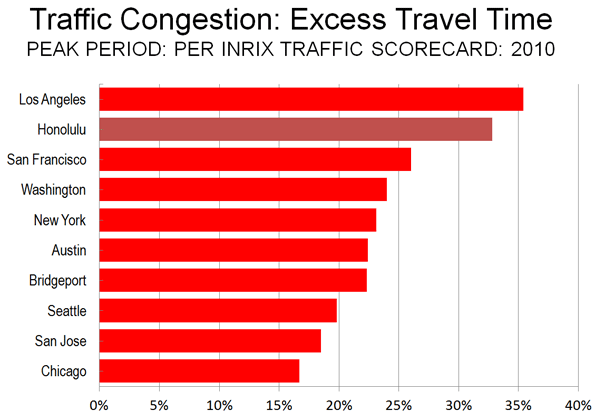

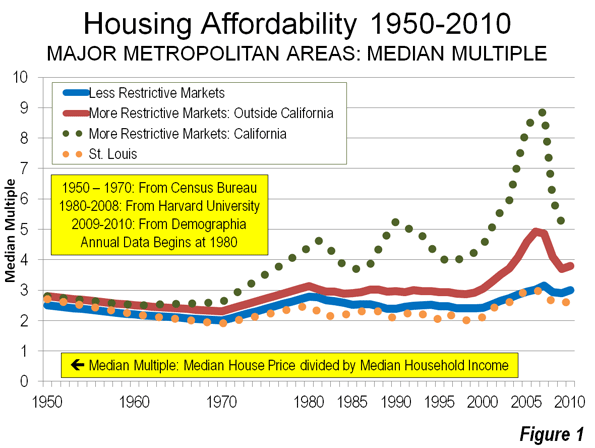

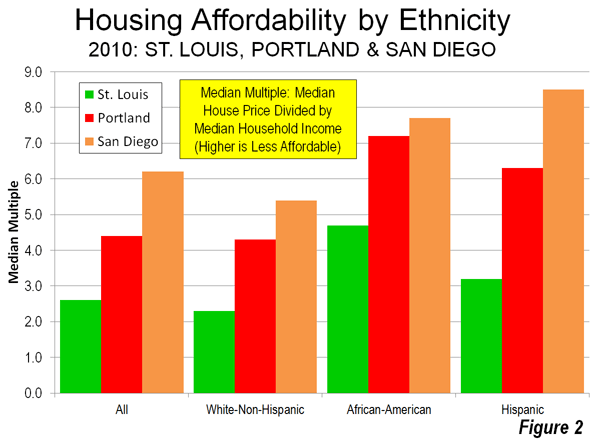

There is an abundance of examples like these, and the key to understanding how they influence decision-makers lies in the conflation of specific amenities with the overarching concept of Smart Growth. For example, Todd Litman’s Where We Want to Be, published by the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, claims that “preference for smart growth is increasing due to demographic, economic and market trends such as aging population, rising future fuel prices, increasing traffic congestion, and increasing health and environmental concerns.”

Does this mean most seniors – such as those in Maryland – want to live in high density, mixed use, transit-oriented apartments even when they say they don’t? Hardly. Litman concedes that “most Americans prefer single-family homes,” but finds “a growing portion want neighborhood amenities associated with Smart Growth including accessibility, walkability, nearby services, and improved public transport.”

Those amenities are things like sidewalks, which evidently are now a Smart Growth invention, and shops that are close to (but not mixed into) residential areas. Litman’s clever construction – e.g., sidewalks equal walkability equal Smart Growth policy – is convincing to officials who mistakenly conclude that their constituents must want Smart Growth when, in fact, they do not.

This has been Part One of a Two-Part Series on Smart Growth by Ed Braddy.

Photo by W. Cox: Rail station in Evry, a suburb of Paris

Ed Braddy is the executive director of the American Dream Coalition, a non-profit organization promoting freedom, mobility and affordable homeownership. Mr. Braddy often speaks on growth management related issues and their impact on local communities. He can be reached at ed@americandreamcoalition.org.