The following excerpts are from a report that was intended to solve many of the planning issues facing one of America’s largest cities: Detroit. Its conclusions are in many ways counter to the ‘Smart Growth’ principles being promoted by influential decision makers. It was compiled by the city’s highest level planners and engineers:

“One disadvantage under which Detroit is working is the extremely mixed character of its building – fifty thousand dollar houses, warehouses, saloons, institutions, slums, factories of all sorts, inexpensive dwellings, great apartment houses, and huge billboards follow one another almost in the same block, to the great detriment of practically all classes of occupancy. A zone system, if established, would bring order out of this chaos; and it would so stabilize the character of neighborhoods as to greatly increase land values. Though such control may at present be impossible, much may be done to assist in establishing zones or districts confined to one type of use, such as residential, industrial, and the like.”

This suggests that the ‘Smart Growth’ goals of mixed uses and mixed incomes may not be so ‘smart’.

Of course, those who believe in intermixing all sorts of uses and incomes on the same block refer to cities where, a century ago, such a mix was normal, and suggest that the isolation of modern transitional zoning is a far worse option.

As we read further:

“In this report, stress will be laid on the less expensive residential development, for which… if the street and lot system is not well adapted to it, there will result serious and at the time wholly unnecessary waste and expense. Moreover, the added cost in land and improvements is apt to cause a deduction in the cost of the building which will lower the standard of living in an entire district.”

In other words, this report is referring to the importance in lower income residential development to create the most efficient form of streets and infrastructure. This would free up funds that would have otherwise been used for wasteful design to be applied to housing. The results of reducing wasteful construction would enhance living standards, instead of lowering them. The authors of this report understood the importance of efficiency, and how it relates to the welfare of residents outside the gentrified sections of the city. The report goes onto recognize one of the most important financial aspects of development:

The house should normally represent three fourths of the cost; the improvements, such as sewers, sidewalks, etc. about an eighth; and the raw land an eighth.

Why is this so critical? Before the current housing market crash and the resulting depletion of American bank accounts, home builders traditionally stood by this model. But after the dot-com bubble, where investors put their money into vapor-ware only to see their investments disappear, the new favorite investment became land and buildings. In many areas of the country developers and national home builders went on a bidding spree, hiking raw land prices into the stratosphere. In the past, the financial rule was that a completed lot could not exceed 1/4th the total home price. The ‘rule’ was now broken, ignored or modified. Financial institutions also turned their heads away. Had the real estate market continued to hold fast to the above formula that served history so well, there may not have been a housing crash.

The report questions another aspect of ‘smart growth’, too:

“No Alleys. Alleys are unnecessary and wasteful of room, except where dwellings are in continuous rows or in groups of three or more. For detached and semi-detached cottages the space between adjacent houses necessary for light and air is sufficient also for a walk from the street to the back door.”

While alleys are fodder for heated discussions from many sides of the planning field, clearly this city’s planners do not like them, yet this particular city is full of alley-laden blocks. Those that blame poor planning on the automobile embrace alleys as a way to hide cars in the rear yards. What this actually does is literally surround the home with pavement and vehicle use-areas. Instead of reducing the connection between home and automobile, it increases the connection. The authors clearly recognize this, and go on to promote common gardens and play areas in the rear yards instead.

The report is very specific about street design. It suggests that the streets be sized for the traffic count, rather than creating unnecessarily wide streets everywhere, perhaps recognizing that too many cities have one size that is supposed to fit all. Unfortunately, planning and engineering consultants often seem to feel, inexplicably, that a short cul-de-sac in a city serving 10 lots somehow carries the same traffic as a street with ten times or more that number of homes. Many sections of Las Vegas, for example, from the air look like a sea of paving and rooftop – and that’s in the suburbs!

The report addresses street grids, as well:

“In rough topography the rectangular and the formal have no place, as they require heavy construction expense otherwise unnecessary. Even in flat country… the depressingly monotonous effect of the rectangular system should be avoided, on economic grounds if no other, for the dead level of mediocrity to which it brings districts depreciates their total value very materially. While to be sure no site is worth very much less than the average, none is worth very much more, whereas with variety in the layout many lots may be created with unusual value, due to location, attractive outlook, and special shape of lot adapted to the needs of the particular resident.”

Oh my, such harsh words against the very grid pattern that the ‘Smart Growth’ movement promotes. It seems that the authors are suggesting a much more organic design, which can eliminate the monotony that detracts from housing and community values. It would seem that the very rigid relationships that are being promoted by ‘smart code’ proponents would not be embraced in this city, at least not by the top level staff and advisors.

The details of this report?

Published by the Commission

1915

It was located in the Cornell University Archives library annex. Called Detroit Suburban Planning, and authored by Arthur Coleman Comey, Landscape Architect, it was based on the preliminary plan for Detroit by Edward H. Bennett, Architect. It included input from the commissioner of parks and boulevards, the commissioner of public works, and the city engineer.

I grew up just outside the border of Detroit in the 1950s and early 1960s. It seemed that, for the most part, development continued on the same grid patterns, ignoring this report for at least the 40 years that followed its publication.

Today, to provide a hope for sustainability for Detroit, we need to heed the report and provide better housing for those that cannot live in architectural wonderlands that only the wealthy can afford, or be subsidized by tax dollars that are no longer available. The development process of trying to jam each and every unit allowed by a regulation’s most minimal dimension in order to achieve the highest possible density pretty much guarantees that the development will fall into the very same traps that the report warned us about.

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and Neighborhood Innovations, LLC. He is author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable and creator of Performance Planning System. His websites are rhsdplanning.com and performanceplanningsystem.com. To learn more about the kind of communities described in the report, check out Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design’s Landscape Urbanism writings and programs, or, to learn more about Prefurbia as applied specifically to this kind of redevelopment, click http://www.rhsdplanning.com/redev.swf (to request a DVD, contact rharrson@rhsdplanning.com.

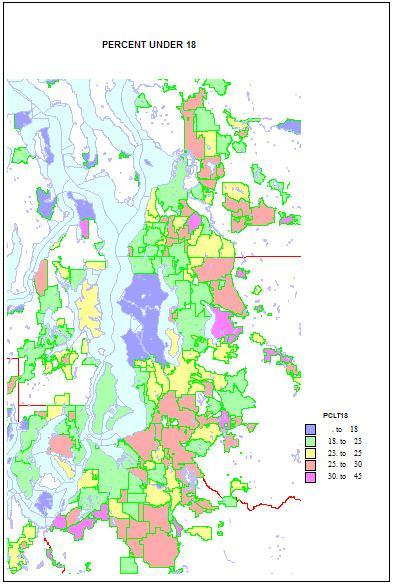

Higher shares of persons under 5 reveal areas of young families. The highest shares are in military bases and Latino towns in eastern Washington, but are quite high, over 12 percent, in the farthest suburban and exurban places around Seattle such as Duvall and Snoqualmie. They are lowest in retirement towns, on islands such as Vashon and Bainbridge, and in some college towns such as Pullman.

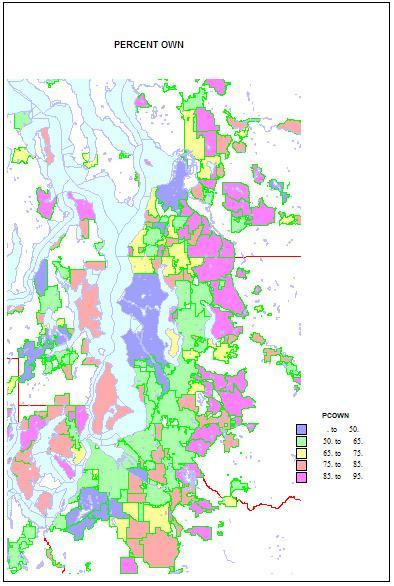

Higher shares of persons under 5 reveal areas of young families. The highest shares are in military bases and Latino towns in eastern Washington, but are quite high, over 12 percent, in the farthest suburban and exurban places around Seattle such as Duvall and Snoqualmie. They are lowest in retirement towns, on islands such as Vashon and Bainbridge, and in some college towns such as Pullman. Home ownership is related to both age and household types. Rates of home ownership are extremely high, in the 90s in newer and more affluent suburbs, with mainly single family homes; the rates are lowest on military bases, college towns, and in a few less affluent suburbs, such as Tukwila. As for the city of Seattle — which has indeed changed its character in a fundamental way — home ownership has dropped to a low of 48 percent. This shift helps us understand the cleavages in Seattle’s body politic, as a formerly very middle class city adjusts to an influx of singles, renters, and young people.

Home ownership is related to both age and household types. Rates of home ownership are extremely high, in the 90s in newer and more affluent suburbs, with mainly single family homes; the rates are lowest on military bases, college towns, and in a few less affluent suburbs, such as Tukwila. As for the city of Seattle — which has indeed changed its character in a fundamental way — home ownership has dropped to a low of 48 percent. This shift helps us understand the cleavages in Seattle’s body politic, as a formerly very middle class city adjusts to an influx of singles, renters, and young people.

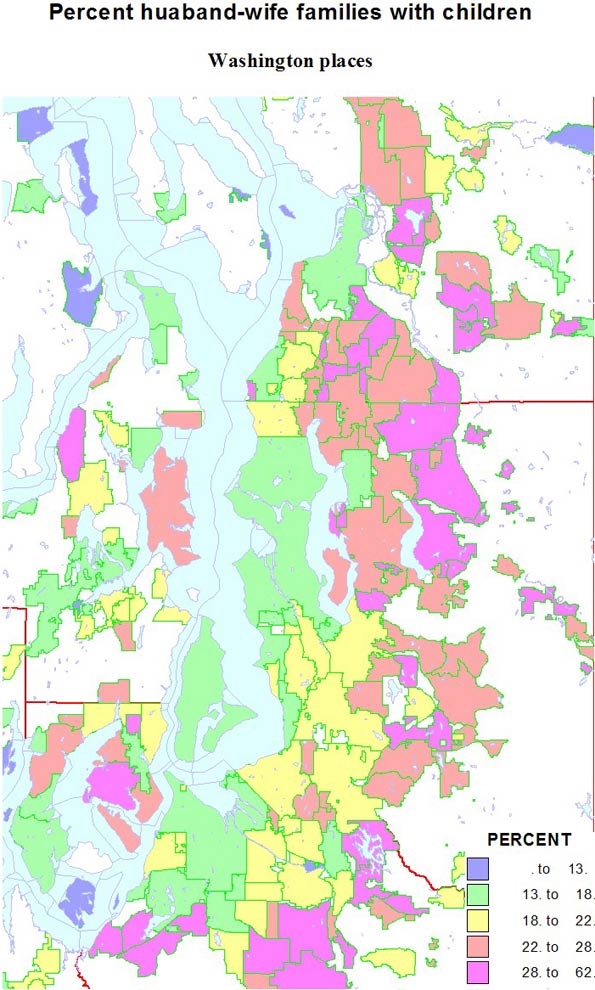

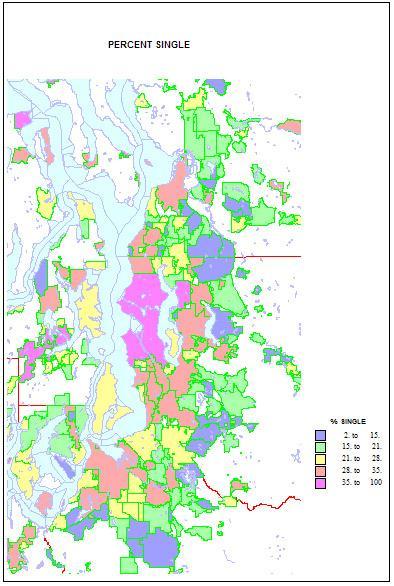

Conversely, singles are highest in two island towns, Friday Harbor and Langley, but Seattle is an extremely high 41 percent. Shares are lowest in the same new suburbs rich in families, as in Sammamish, at 11 percent. Shares of unmarried partners are a high 10 percent of households in Seattle, but are higher on Indian reservations and the cities of Hoquiam and Aberdeen. The share of single-parent households is also high on Indian reservations, in less affluent and more ethnic suburbs like Parkland and Bryn Mawr and Tukwila. It is lowest in the newer, family-filled far suburbs.

Conversely, singles are highest in two island towns, Friday Harbor and Langley, but Seattle is an extremely high 41 percent. Shares are lowest in the same new suburbs rich in families, as in Sammamish, at 11 percent. Shares of unmarried partners are a high 10 percent of households in Seattle, but are higher on Indian reservations and the cities of Hoquiam and Aberdeen. The share of single-parent households is also high on Indian reservations, in less affluent and more ethnic suburbs like Parkland and Bryn Mawr and Tukwila. It is lowest in the newer, family-filled far suburbs.