We live in an era of the heady drumbeat of urban triumphalism. In a world that is now, by some measures, predominately urban, observers like historian Peter Hall envision a “coming golden age” of great cities. It is time to look at such claims more closely, replacing celebratory urban legends with careful analysis. Although the percentage of people living in cities is certain to grow, much of this growth will be in smaller cities, suburbs and towns. And it is unclear whether extreme centralization and densification are either inevitable or desirable, for as cities get larger—both in the developed and developing world—they display a tendency to become increasingly congested, bifurcated by class and economically inflexible.

It may be time to propose a less gargantuan vision that is more humane for the vast majority of people. This alternative view embraces not cramming and concentration— the favored strategies of most planners, pundits, architectural stars and their urban land-owner enablers—but the protean development of more dispersed and less concentrated cities and suburbs. This is what is happening in most cities in the world today, and has been the pattern of urban areas throughout history.

There are numerous signs that this reality is taking root, both in the developing world and in high-income countries. Shlomo Angel, a lecturer at the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton, has shown that as the world’s urban population has grown, the percentage living in the 100 largest cities has declined. Between 1960 and 2000, the share of the largest cities declined from nearly 30 percent to closer to 25 percent. Since the nineteenth century, notes Angel, urban population densities have declined, as people have sought out less dense, more appealing, and usually less costly locations on the periphery. This is true, he points out, in London and even to some extent Mumbai, as well as in the United States. As the World Bank has noted: “Cities became more packed and more sprawling at the same time.”

What may be best is to forge not an agenda for centralization, but policies that promote both smaller cities and villages. This, notes Ashok R. Datar, chairman of the Mumbai Environmental Social Network and a long-time advisor to the Ambani corporate group, may represent the most practicable strategy for relieving the unbearable congestion that threatens so many mega-city environments.

Down from the Commanding Heights

The dispersionist viewpoint challenges the assumption that the bigger, more densely packed a city is, the better. This approach appeals to prominent urbanists, such as the University of Chicago’s Saskia Sassen, who see such places as the inevitable occupiers of the (Leninist) “commanding heights” of the global economy. To spread out economic growth, a World Bank report asserts, is to discourage it.

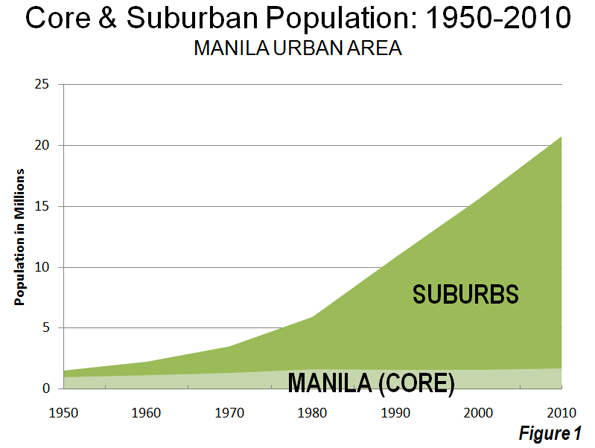

The dispersionist view begs to differ. In many important ways, the largest urban agglomerations can also be seen as gradually losing their edge to more smaller cities. One of the ironies of this Age of Cities lies in the fact that relative size is no longer the overwhelming critical advantage as was the case in the less urbanized past. Before the late twentieth century, big cities were efficient and economically viable. The greatest urban centers of history—Babylon, Rome, Constantinople, Paris, London, Kaifeng, Baghdad, New York, Tokyo—grew in part because concentration provided the best, and sometimes only, way to support the basic infrastructure for commerce, cultural development, state religion or the exercise of power. But increasingly size not only matters less, but actually can be seen as a detriment to efficient, sustainable urbanism. This is particularly evident in the developing world where urbanization is spreading most rapidly. With the exception of Tokyo, the world’s most populous urban agglomerations—Delhi, Mumbai, São Paulo, Mexico City—have evolved into almost unspeakably congested leviathans, plagued by both deepening class divides and environmental problems.

By 2025, cities in developing countries are projected to account for eight of the ten world’s largest cities. Four will be located in the Indian subcontinent alone, and each will accommodate twenty million or more residents. They may be seen as “colorful” by what one writer calls “slumdog tourists,” and “exciting” for those working within the confines of their “glamour zones,” but for most of their citizens life will be very difficult, and better only compared to what are even more dismal conditions in the countryside.

Over the past forty years, the percentage of Mumbai’s population living in slums has grown from one in six to a majority. One indicator of the conditions there: the average Mumbaiker’s lifespan is now seven years less than the national average. This is all the more remarkable since most Indians still live in villages with very limited sanitation and even less access to quality health care. Concentrating more people in Mumbai or other developing mega-cities represents a form of lunacy. Much the same can be said for Kolkata, Manila, Cairo, Mexico City, and Lagos.

On the other hand, the dispersionist notion emphasizes second and third tier city development. Already many Indian businesses and skilled workers are moving to smaller, less congested, often better-run cities such as Bangalore, whose density is roughly one-fourth of Mumbai’s, or Ahmadabad in the state of Gujarat. Much of this new growth takes place in campuslike settings on the edge of the city that take advantage of newer infrastructure and offer workers a less harried way of life. Many of India’s key industries—auto manufacturing, software and entertainment— are establishing themselves in such smaller cities, which are far less dense and less populated than Mumbai or Kolkata.

In a more planned fashion, China is embracing decentralization, encouraging growth in smaller interior cities such as Chengdu, Wuhan and Xi’an. Such cities, notes Chengdu-based architect Adam Mayer, offer a healthy alternative to the coastal megacities of Shanghai, Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou. China’s bold urban diversification strategy hinges both on forging new transportation links and on nurturing businesses in these interior cities.

Such commitment, and the resources to fund it, are lacking in much of the developing world. Africa, for example, now boasts many huge, and rapidly growing, cities, but it is hard to describe Lagos in Nigeria, Luanda in Angola, and Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo as places with particularly bright prospects. One exception may be Capetown, the beautiful South African coastal city that shone so well during the recent World Cup. Latin America, too, has a plethora of huge and growing cities, but it is hard to imagine Mexico City and São Paulo as likely hot-spots for future economic growth. Instead the best prospects lie in smaller cities like Santiago, the capital of resource-rich Chile, or Campinas, a growing smaller Brazilian city with three million residents that lies outside the congested São Paolo region.

This shift to smaller cities, as Michigan State’s Zachary Neal points out, has been conditioned by rapid improvements in telecommunications and transportation infrastructure. But perhaps the most conclusive evidence that smaller can be better and more efficient can be found in other parts of the developing world. Cairo, Baghdad, and Tehran are the biggest cities in the Middle East, but they are hardly economic successes. In contrast, Tel Aviv, whose total metropolitan population is only three million, has emerged as a major center for technology as well as one of the world’s premier diamond centers. The other leading candidates in the region hail from the United Arab Emirates, notably oil-rich Abu Dhabi and perhaps also its now financially weakened neighbor, Dubai.

No place illustrates the principle that smaller can be better as well as Singapore. With roughly four million residents, Singapore ranks only sixtieth in terms of population among the world’s cities. But its economy clocks in at twenty-seventh, ahead of much larger Mumbai. In per capita terms, by purchasing power parity, it boasts an income of $62,200, one of the highest in the world, and behind only Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Bermuda, and Qatar (and roughly the same as the United States). This is a remarkable achievement for a city-state whose per capita income at the time of its independence in 1965 was equal to those of other developing countries. Today Singapore boasts one of the world’s largest ports, a highly efficient subway system, and among the world’s most impressive skylines. It is easily the cleanest, most efficient big city in all of Asia. It is noteworthy that Singapore has employed its collective intelligence to develop a socially, economically and increasingly environmentally viable city in a space of only 268 square miles.

The High-Income World

The dispersionist reality is also evident in the high-income world. Even though some city cores have improved markedly, the largest and densest urban regions have performed somewhat worse than newer, smaller and often less compact urban areas. This decentralizing trend can also be seen in the western United States. In 1965, New York presided over the American economy like a colossus, accounting for more than 150 of the nation’s 500 largest companies; today that number is fewer than fifty. Not far behind New York are Los Angeles and Chicago, which also claim the coveted status of “world city.” In the meantime, a host of smaller and far more dispersed Texas cities have come to the fore. Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and Austin enjoy the most rapid job and population growth of the nation’s largest metropolitan regions. Houston, which replaced New York as the center of the global energy industry, now has more Fortune 500 companies than Chicago. Together, the four Texas cities boast more large company headquarters than greater New York.

But this movement from large dense cities to less dense ones represents only part of the dispersionist trend. A more critical one involves the movement from larger cities to smaller ones. In fact, between 2000 and 2008, notes demographer Wendell Cox, regions of more than ten million suffered a 10 percent rate of net outmigration. The big gainers were cities between 100,000 and 2.5 million residents. The winners included not only cities in Texas, but also southern urban regions such as Raleigh-Durham, now the fastest growing metro area over one million in the nation, and Nashville, and rising Heartland cities such as Columbus, Indianapolis, Des Moines, Omaha, Sioux Falls, and Fargo. Among urban areas of over one million, Columbus, Raleigh, Indianapolis, Denver and Kansas City all rank considerably ahead (in terms of growth of educated migrants between 2007 and 2009) of megacities such as New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, according to the most recent American Community survey. One key advantage for these smaller cities is the price of housing. Even after the real estate bust, according to the National Association of Home Builders, barely one in three Los Angeles median-income households can afford a median-priced house; in New York, that ratio falls to one in four. In contrast, in regions such as Raleigh, Austin, San Antonio and Indianapolis, between two in three or four in five can afford the American dream. Advocates of dense cities mega-regions often point out that many poorer places, including old Rustbelt cities, enjoy high levels of affordability while regions such as New York do not. But that does not mean that affordability itself is a problem; areas with the lowest affordability, including New York, also have suffered among the high rates of domestic outmigration. The formula for a dynamic region mixes affordability with a growing economy.

The smaller cities also are often easier for workers and entrepreneurs in which to do business. Despite the presence of the nation’s best developed mass transit system, the New York area has the longest commuting travel times; the worst are in Queens and Staten Island. As a general rule, average commuting time also tends to be longest in some of the biggest denser cities, notably New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. In contrast, the average commutes in places like Salt Lake City and Kansas City are slightly above twenty minutes. Over a year, moving to these smaller cities can save roughly 70 hours a week in commuting time.

Finally there is the critical social issue. The largest cities such as New York and Los Angeles also tend to suffer the most extreme polarization of incomes. New York, for example, now has a distribution of wealth roughly twice as concentrated at the top than the national average. In 1980 Manhattan ranked seventeenth among the nation’s counties for social inequality; by 2007 it ranked first, with the top fifth of wage earners earning fifty-two times that of the lowest fifth, a disparity roughly comparable to that of Namibia. This is not only an American phenomenon. A study of the core city of Toronto, for example, found that between 1970 and 2001 the portion of middle-income neighborhoods in the city had dropped from two thirds to one third, while poor districts had more than doubled to 40 percent. By 2020, according to the University of Toronto researchers, middle-class neighborhoods could fall to barely less than 10 percent, with the balance made up of affluent and poor residents.

Increasingly, one sees income gaps in high-income country megacities that one normally associates with developing countries. This is particularly true in expensive megacities whose finance-driven economies create high costs but lesser opportunities for middle and working class families. Once cost of living is factored in, more than half the children in inner London live in poverty, the highest level in Great Britain. More than one million Londoners were on public support in 2002.

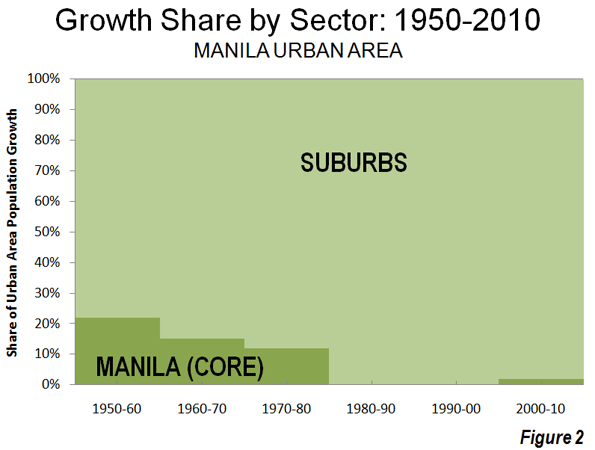

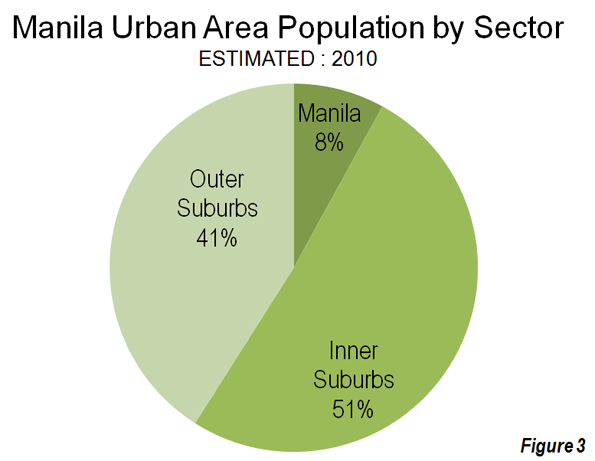

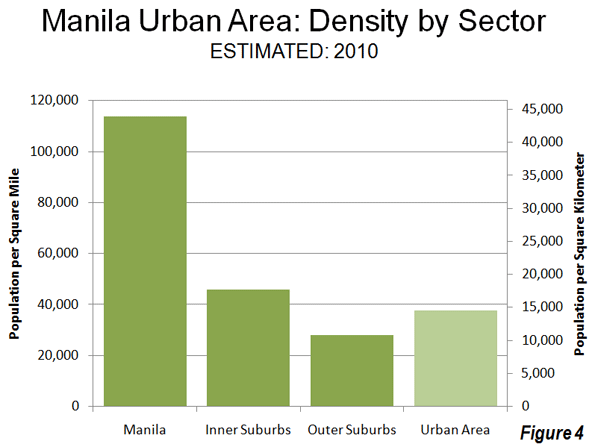

The Triumph of Suburbia

We can see the impact of dispersion not only in the movement between cities but also in population shifts within them. Even the great metropolitan areas are, for the most part, de-concentrating. They increasingly boast not one center but a series of smaller ones, some far from the urban core. This can also be seen in both developing and high-income cities. The new business center of Mexico City, for example, is located in suburban Santa Fe and not the historic core. Much of the Mumbai entertainment complex known as Bollywood long ago migrated to the northern suburbs, with their malls and less dense neighborhoods.

This pattern can be seen even more in the high-income countries. In virtually every major city in Europe, the urban core now represents a smaller percentage of the metropolitan population than two decades ago. Cities such as London, Paris, Frankfurt and Madrid, despite the presence of excellent mass transit, are far more suburbanized and decentralized than they were two decades ago. Since 1965, virtually all European major metropolitan area growth has been in the suburbs. Indeed, the share of the metropolitan area population gains in the suburbs has been greater in Western Europe than in the United States. As in the United States, this reflects in part the shift of technology industries into suburban areas. The reasons for this may have much to do with the family-oriented nature of many engineers and scientists, and their preference for campus-like settings. This is true both in the Grande Couronne around Paris, where many French tech firms cluster, and in Great Britain. The dynamic growth in fields such as technology and high-value-added and design-led manufacturing are concentrated not in the core, or even the surrounding suburbs, but in the outer reaches of the Thames Valley and around Cambridge. New home-work opportunities and attractive housing concentrates workers in such places, as well as in cities such as Bath and Taunton. “Cities,” concluded one recent report by the British Urban Regeneration Association, “are no longer the main source of new enterprises.”

This statement will be familiar to people who study North America. For all the talk about new media and other tech related fields clustering in “hip and cool” urban cores, the greatest concentrations of technology industries are in predominately suburban areas, such as those on the periphery of Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto, or Route 128 around Boston, Orange County, California and the hill country around Austin, Texas. One reason is that the brain power is there. According to the United States Census, eighteen of the nation’s twenty counties with the highest percentage of college-educated people over twenty-five are in either suburban or small cities.

Silicon Valley, the world’s predominant high-tech concentration, remains to a large extent a vast suburb. The headquarters of such firms such as Intel, Apple, and Google are not in urbanized, transit-oriented San Francisco, but in sprawling, car-dominated places like Santa Clara, Cupertino and Mountain View. Although there are some pockets of density, the Valley essentially functions along suburban lines with no significant real urban core. Transit ridership in the Valley now stands at 3 percent, closer to a Phoenix or Houston than a New York or San Francisco.

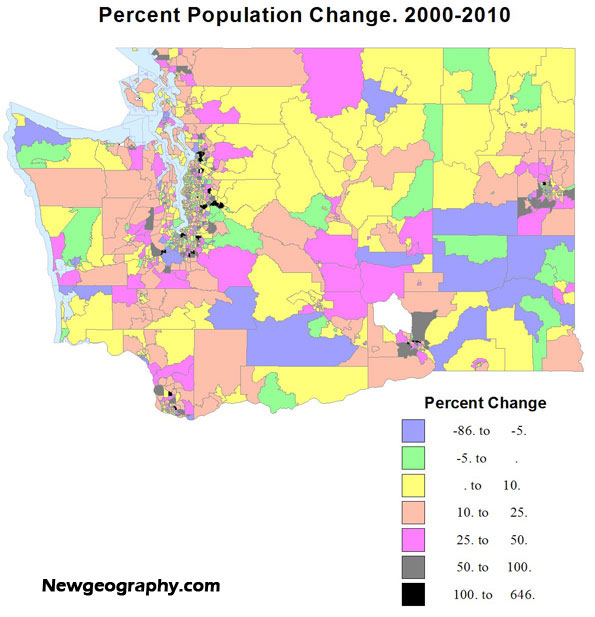

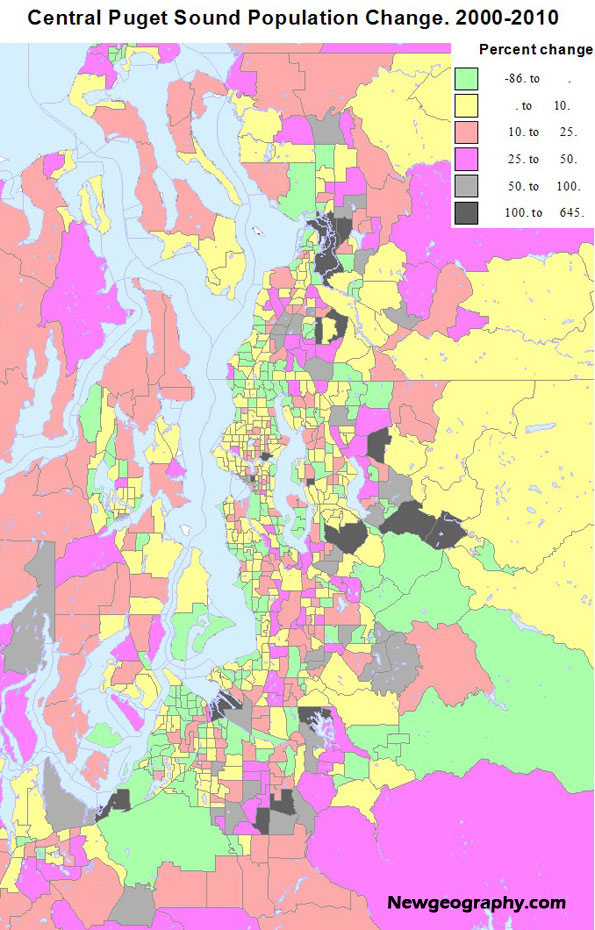

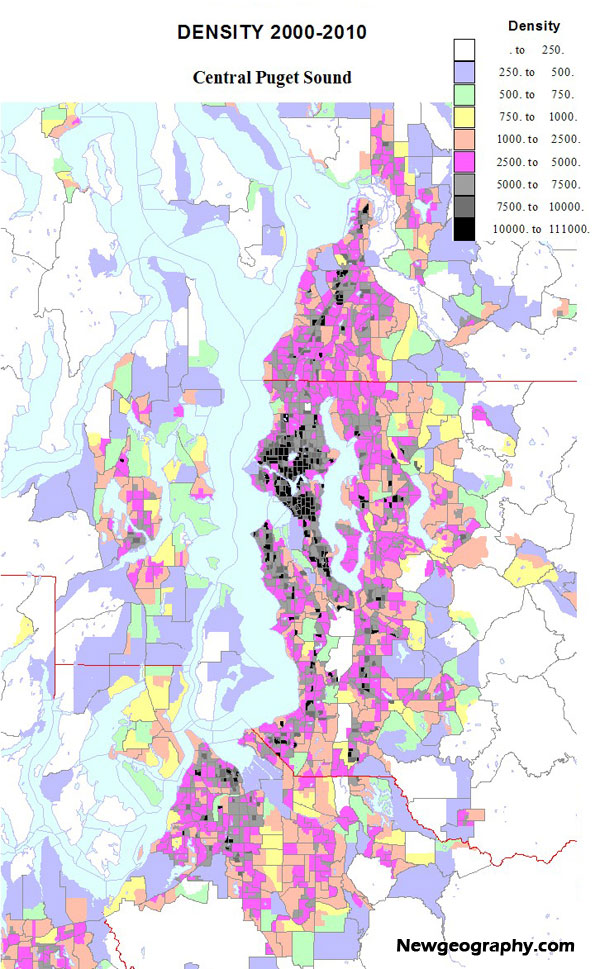

These economic trends are also reflected in demographics. Nationwide, over the past decade, suburbs have accounted for 85 percent of all metropolitan growth. Over the past decade, out of the forty-eight metropolitan areas, suburban counties gained more migrants than core counties in forty two cases; virtually all the fastest-growing communities in the country over the past decade have been located on the suburban fringe. Another indicator: Despite all the talk of people moving “back to the city” to experience the joys of density, between 2000 and 2008, the share of households living in detached housing rose from 61.4 percent to 63.5 percent.

The Urban Future

Whether in the high income or developing world, the evidence suggests our urban future will be more diverse—and dispersed—than commonly assumed. Like the housing around some suburban areas, there has also been a crash in many inner city markets.

As a result of overestimating the demand for high density, there are sad stretches of abandoned or drastically devalued highrise and mixed-use areas in Miami, Kansas City, Chicago, Los Angeles and even the core of Portland, where condo prices have tumbled by at least 30 percent since 2007.

Rather than force a density agenda on a largely unwilling population, it is better to consider how to make the more dispersed urban future more workable and sustainable. In the developing world, this might include the development of regional employment centers to reduce the often unbearable congestion of the urban core. At the same time, more thought should be given to allowing for houses on small lots, which could serve as gardens or placing for small household industry. In the high-income countries, there will be new opportunities in what may have once been considered second-tier markets to develop new urban amenities. There will be similar openings in the suburbs and even exurbs. Although these areas will not become densely packed, they will become more urban in many ways.

Much also can be done to make our dispersing geography more environmentally friendly. Recent studies by environmental scientists in Australia suggest that the carbon footprint of high-rise urban residents, contrary to the conventional wisdom, is higher than that of medium and low-density suburban homes, due to the cost of heating common areas such as parking garages, and the highly consumptive lifestyles of more affluent urbanites, a considerable number of whom own second residences in the countryside. Even if these claims are exaggerated, there is no question suburbs and lower-density cities can be made more environmentally sustainable by such relative low-cost, relatively unobtrusive steps, these including insulation and tree-planting as well as the adoption of more fuel-efficient automobiles and a greater embrace of telecommuting, which is by far the fastest form of commute to work.

Instead of clinging to the idea that density and concentration are best, planners, architects and developers would do better to focus what appeals to the vast majority of the population, particularly the middle and working classes. Nurturing smaller, more efficient cities, as well as expansive suburbs and revived small towns, may prove far more practical and beneficial to society than imposing the manic agenda among planners, pundits and urban land speculators for relentless centralization.

This piece originally appeared in Wharton Real Estate Review.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.

Photo by Paul Sapiano