During the first ten days of October 2008, the Dow Jones dropped 2,399.47 points, losing 22.11% of its value and trillions of investor equity. The Federal Government pushed a $700 billion bail-out through Congress to rescue the beleaguered financial institutions. The collapse of the financial system in the fall of 2008 was likened to an earthquake. In reality, what happened was more like a shift of tectonic plates.

*******************************************

The driveway tells the story. The traditional two-story 2,200 square foot suburban home has a two-car attached garage. Today’s multi-generational families fill the garage, the driveway and often also occupy the curb in front of the home. The economic crisis that is transforming America is also changing the way we live. The outcome will change the way America views its housing needs for the balance of the 21st Century.

As is often the case, we can more clearly see the future by looking into our past. That is because time and time again America has reverted to its roots when confronted with a challenge. The root of the American family is the home. A century ago, America was an agrarian nation. Most Americans grew up on the farm or in a small town often tied to agriculture. A century ago, our census was 92,000,000, less than one-third of today’s population. Los Angeles was a city of 319,000. Cleveland was the fifth largest city with 560,000. The tenth largest city in 1910 was Buffalo NY with 423,000 souls.

A century ago, parents, children, grown children, and grandparents lived together in America’s homes. In 1910, the vast majority of kids did not go off to college. They stayed home and worked the farm. Mom certainly did not drive and usually she did not work outside the home. Grandma – who then as now usually outlived grandpa – did not go off to an active senior housing project or nursing home at age 55. With the average life expectancy at just 49 years, there was little market for such facilities. A young Grandma lived in the family home and helped with the cooking, the sewing and the child rearing.

Along the way, we fought in two world wars, America industrialized and the great Middle Class exploded. Our children went off to college and did not return. Our cities exploded. By the end of the century, Los Angeles grew to 3,700,000. The tenth largest city was Detroit with 1,000,000. Children were expected to leave the home shortly after high school and never come back, except to visit.

Big changes occurred on the other end of the demographic curve. As life expectancy grew to 75. Grandma had her choice of active senior living, congregate care or a skilled nursing facility when she hit 70 and slowed down.

The expectations of greater family dispersion – with young people leaving home early and grandparents on their own – drove much of real estate thinking at the end of the 20th Century. With empty-nesters and young people both heading back to the city, urban planners were focusing on high-rise apartments and condominiums in dense urban areas. Many eagerly anticipated the death of the suburbs since the number of young families declined. Across the country, and even in suburban areas like the City of Irvine, CA brilliant urban planners began rezoning industrial land into high density housing. The face of America was thought to be changing in predictable ways.

Then, along came 2008 and the economic crisis. The plates under our feet began to shift. The mass migration to dense urban living evaporated as people stayed put and speculating in condos lost all economic logic. The shiny new urban corridor in Irvine now lined with high rise housing sits empty, with many units vacant and foreclosed. In nearby Santa Ana, twin 25-story residential towers sit eerily vacant with not a single unit sold or occupied. Central Park, a giant new urban project in Irvine that boasted dense high-rise, townhouse and mid-rise units, sits vacant behind green security fences.

Where did the buyers go? Many young people moved back home with their parents when their high paying jobs in real estate or mortgage brokerage disappeared. With their jobs and income gone, they sought refuge in the safety of their childhood homes. Their parents ended any speculation of selling and down-sizing when their children returned. With job creation non-existent, they do not plan on leaving anytime soon. In one recent Pew study, 13 percent of parents with grown children reported one of their adult offspring had moved back home in the past year. Roughly half of the population 18 to 24 still lives with their parents.

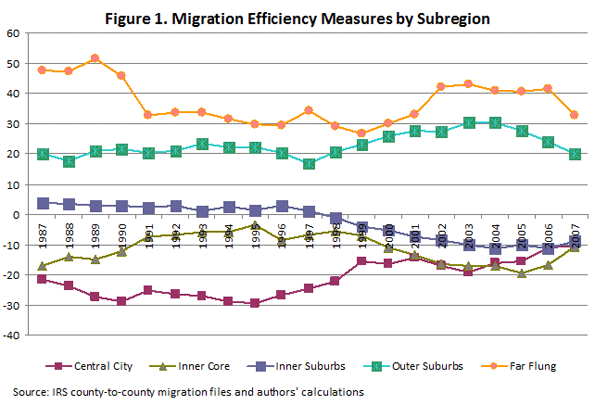

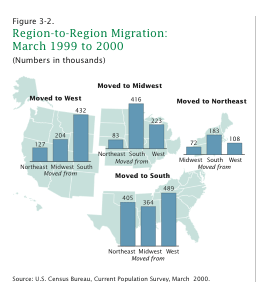

This stay-at-home trend predates even the recession. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the national relocation rate in 2008 was the lowest since the agency started tracking the data in 1948. The rate was 11.9 percent in 2008, a decline from 13.2 percent in 2007. The 2008 figure represents 35.2 million people, which is the smallest number of residents to move since 1962. The number was 38.7 million in 2007.

What about Grandma and, increasingly, even Grandpa? Our parents, thanks to the miracle of modern medicine, are living longer than ever. If she has reached age 65, she can expect to live another 20 years. Unfortunately, her retirement account and savings plan may not. Many Americans are living well into their 90s and we will see the first wave of centurions in our lifetime. No one expected this to happen and we are unprepared for it. Grandma will not be able to afford the $3,000 to $4,000 a month expense of a quality retirement facility – for 20 years.

This changing dynamic will alter movement of Americans, which has now been slowing down for a generation. In 1970, nearly 20 percent of Americans changed their place of residence every year. But by 2004, that figure had dropped to 14 percent, the lowest level since 1950. The tough economy and aging demographics will slow migration down even more. Mom and Dad will not find it easy to take that new position in another city with the kids at home and now Grandma, and even Grandpa, too.

This will have profound impact on the kind of housing Americans will want. Homebuilders may find lower demand for single family houses as America doubles up but it will be the much ballyhooed drive to urbanize America with dense high-rise units that is most in danger.

Extended families will want larger – not smaller – houses. They may not be able to afford McMansions, but conventional suburban houses will be changed to meet the demands of extended families. Granny flats, consisting of self contained ground floor units, will be in demand as the baby boomer generation moves into retirement. Smaller single floor homes called Casitas will need to be mixed into planned developments so that the Grandparents can live closer to the children.

City staff and urban planners, already grappling with a mandate to accommodate global warming and carbon footprints, will have to rethink existing zoning rules which have not yet responded to the new reality. This reality will be driven by aging demographics, diminished capital and the shifting plates of our economy. The baby boomer “bubble” that is now beginning to retire is a well established fact. Lesser known is the impact of the financial crisis on young workers who simply have been priced out of the housing market. Along the pricier coasts and Northeastern cities, they will need the down payment from their parents – who in exchange will live with their kids – to purchase their own home.

The kids have already come home. Like the financial downturn, they will not be leaving anytime soon. Grandma is next in line. When she comes home, the circle will be complete, with consequences few in the real estate industry have yet to contemplate seriously.

**********************************

This is the sixth in a series on The Changing Landscape of America. Future articles will discuss real estate, politics, and other aspects of our economy and our society.

Robert J. Cristiano PhD is a successful real estate developer and the Real Estate Professional in Residence at Chapman University in Orange, CA.

PART ONE – THE AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY (May 2009)

PART TWO – THE HOME BUILDING INDUSTRY (June 2009)

PART THREE – THE ENERGY INDUSTRY (July 2009)

PART FOUR – THE ROLLER COASTER RECESSION (September 2009)

PART FIVE – THE STATE OF COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE (October 2009)