Not for the first time, reality and politics may be on a collision course. This time it’s in respect to the costs of strategies intended to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Waxman-Markey “cap and trade” bill still awaits consideration by the US Senate, interest groups – mainly rapid transit, green groups and urban land owners – epitomized by the “Moving Cooler” coalition but they are already “low-balling” the costs of implementation.

But this approach belies a bigger consideration: Americans seem to have limits to how much they will pay for radical greenhouse emissions reduction schemes. According to a recent poll by Rasmussen, slightly more than one-third of respondents (who provided an answer) are willing to spend $100 or more per year to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. About 2 percent would spend more than $1,000. Those may sound like big numbers, but they are a pittance compared to what is likely to be required to meet the more than 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions that the Waxman-Markey bill would require. Even more worryingly for politicians relying on voters to return them to office, nearly two-thirds of the respondents would pay nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

If we do a rough, weighted average of the Rasmussen numbers, it appears that Americans are willing to spend about $100 per household per year (Note 1). This includes everyone, from the great majority, who would spend zero to the small percentage who would spend more than $1,000. At $100 per household, it appears that Americans are willing to spend on the order of $12 billion annually. This may look like a big number. But it is peanuts compared to market prices for greenhouse gas emissions. This is illustrated by the fact that the social engineers whose articles of faith requires building high speed rail to reduce greenhouse gas emissions would spend $12 billion to construct just 150 miles of California’s proposed 800 mile system.

Comparing Consumer Tolerance to Expected Costs: At $100 per household, Americans are prepared to pay just $2 per greenhouse gas ton removed. All of this is in a policy context in which the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggests that $20-$50 per greenhouse gas ton is the maximum that should be spent per ton. The often quoted McKinsey/Conference Board study says that huge reductions in greenhouse gas emissions can be achieved at $50 or less, with an average cost per ton of $17. International markets now value a ton of greenhouse gas emissions at around $20. At $2 per ton, American households are simply not on the same “planet” with the radical climate change lobby as to how much they wish to spend on reducing greenhouse gases.

International Comrades in Arms? This is not simply about Americans and their perceived differences from others who are so often considered more environmentally sensitive. France’s President Sarkozy has encountered serious opposition in proposing a carbon tax on consumers to discourage fossil fuel use. He is running into problems not only among members of the opposition, but concerns have also been expressed by members of his own party. It appears that many French consumers (like their American comrades) are more concerned about the economy than climate change at the moment.

China, India and Beyond: If only a bit more than one-third of American households are willing to pay much of anything to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, it seems fair to ask what percentage of households in China, India and other developing nations are prepared to pay anything? A possible answer was provided recently by India’s environment minister, Jairam Ramesh, who released a report predicting that India’s greenhouse gas emissions would rise from the present 1.2 billion tons to between 4 and 7 billion tons in 2030. The minister said the “world should not worry about the threat posed by India’s carbon emissions, since its per-capita emissions would never exceed that of developed countries.” . At the higher end of the predicted range, India would add more greenhouse gas emissions than the United States would cut under even the proposed 80 percent reduction scheme. Suffice it to say that heroic actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions seem unlikely in developing countries so long as their citizens live below the comfort levels of Americans and Europeans.

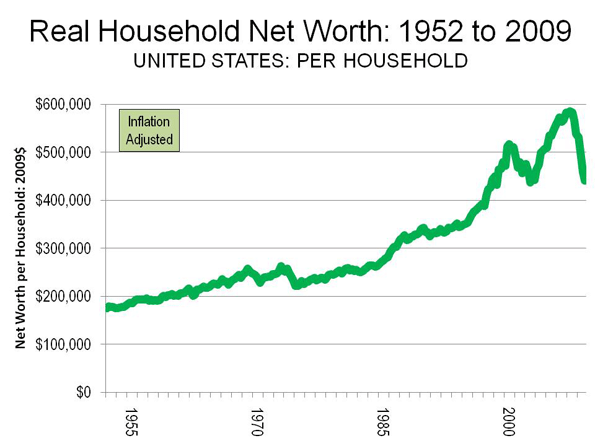

Lower Standard of Living not an Option: I have been giving presentations on this and similar subjects for some years. I have yet to discern any seething undercurrent of desire on the part of Americans (or the vast majority anywhere else) to return to the living standards of 1980, much less 1950 or 1750. Neither Washington’s politicians nor those in Paris or any other high income world capital are going to tell the people that they must accept a lower standard of living. Nor is there any movement in Washington to let the people know that their tolerance for higher prices could well be insufficient to the task.

For Washington, the dilemma is that every penny of the higher costs will hit consumers (read voters), whether directly or indirectly. There could be trouble when the higher utility bills begin to arrive and it could mean difficulty in delivering on the primary policy objective of virtually all governments, which is to remain in power. This is not to mention the unintended consequences of higher prices on many key industries, notably agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation.

There is an even larger concern, however, and that is the stability of society. Harvard economist Benjamin Friedman, in The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth suggested from an economic review of history that economies that fail to grow lapse into instability.

A Public Policy Collision Course? A potential collision between economic reality and public policy initiatives could be in the offing. Many “green” proposals are insufficiently sensitive – even disdainful – towards the concerns of everyday citizens. This suggests that politically there should be an emphasis only on the most cost effective strategies. In a democracy, you must confront to the reality that people are for the most part more concerned about the economy than about strategies meant to slow climate change.

The imperative then is not to ignore the problem, but to focus on the most rational, low-cost and effective greenhouse gas emission reduction strategies. Regrettably, it does not appear that Washington is there yet. The special interests whose agendas are to cultivate and reap a bounteous harvest of “green” profits or to convert the “heathen” to behaviors – such as riding transit and living in densely packed neighborhoods – that they have been advocating long before the climate change issue emerged.

Those concerned about the future of the environment also have to pay attention to reality. Reducing greenhouse gases is not a one-dimensional issue. Environmental sustainability cannot be achieved without both political and economic sustainability.

Note 1: The Rasmussen question was asked of individuals. It is assumed here, however, that the answers related to households. One doubts, for example, that a queried mother answered with an assumption that she would pay $100, her husband would pay $100 and each of the kids would pay $100, but rather meant $100 for the household, since, to put it facetiously, few households devolve their budgeting to the individual members.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

Union Square, San Francisco – Despite an expensive redesign nearly five years ago, Union Square is still not the central urban gathering space for San Francisco. Although it does serve as an incidental focus of pedestrian activity within the immediate neighborhood, the primarily hardscaped design is too fussy and too formal to encourage casual passive use and extended stays, except, perhaps, within limited zones at the fringes. The little available seating is poorly designed, intended to prevent homeless use rather than to promote use by casual park visitors. Primarily a concrete space with grass at the corners, Union Square lacks the “warmth” that makes such spaces comfortable. Imagine a Union Square with a great lawn in the middle, rather than cold (and expensive) hardscape.

Union Square, San Francisco – Despite an expensive redesign nearly five years ago, Union Square is still not the central urban gathering space for San Francisco. Although it does serve as an incidental focus of pedestrian activity within the immediate neighborhood, the primarily hardscaped design is too fussy and too formal to encourage casual passive use and extended stays, except, perhaps, within limited zones at the fringes. The little available seating is poorly designed, intended to prevent homeless use rather than to promote use by casual park visitors. Primarily a concrete space with grass at the corners, Union Square lacks the “warmth” that makes such spaces comfortable. Imagine a Union Square with a great lawn in the middle, rather than cold (and expensive) hardscape. Market Street, San Francisco – Punctuated by intermittent triangular plazas along most of its downtown stretches, portions of Market Street’s public space are more the domain of homeless panhandlers than workers, residents, strollers, and the like (it should be noted, however, that some parts of Market Street, such as in the Financial District, can be pleasant at times). The plazas, quality architecture, and mix of uses create potential. But the pedestrian environment discourages extended dwell times, except by the homeless, panhandlers and drug dealers, many of whom, the city has documented, commute daily to Market Street from elsewhere in the Bay Area. The design offers little in the way of seating options and softscape. Sanitation and maintenance need to be substantially upgraded and programming is needed.

Market Street, San Francisco – Punctuated by intermittent triangular plazas along most of its downtown stretches, portions of Market Street’s public space are more the domain of homeless panhandlers than workers, residents, strollers, and the like (it should be noted, however, that some parts of Market Street, such as in the Financial District, can be pleasant at times). The plazas, quality architecture, and mix of uses create potential. But the pedestrian environment discourages extended dwell times, except by the homeless, panhandlers and drug dealers, many of whom, the city has documented, commute daily to Market Street from elsewhere in the Bay Area. The design offers little in the way of seating options and softscape. Sanitation and maintenance need to be substantially upgraded and programming is needed. Proper seating, adequate lighting, and extensive horticultural displays would serve to populate these public spaces. Proper management and maintenance would ensure long-term success. Places such as Bryant Park in Midtown Manhattan, itself the beneficiary of a remarkable turnaround masterminded by Daniel Biederman of the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, have shown what visionary management can do to struggling urban public spaces. [Kozloff worked for BRV Corp., Biederman’s private consulting company that is independent of the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, from 2001-2004.] Although once run on a city budget of $200,000, Bryant Park is now managed on a privately-funded budget. Biederman turned Bryant Park – once the domain of drug dealers and other such undesirables – into Manhattan’s premier address without using public coffers.

Proper seating, adequate lighting, and extensive horticultural displays would serve to populate these public spaces. Proper management and maintenance would ensure long-term success. Places such as Bryant Park in Midtown Manhattan, itself the beneficiary of a remarkable turnaround masterminded by Daniel Biederman of the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, have shown what visionary management can do to struggling urban public spaces. [Kozloff worked for BRV Corp., Biederman’s private consulting company that is independent of the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, from 2001-2004.] Although once run on a city budget of $200,000, Bryant Park is now managed on a privately-funded budget. Biederman turned Bryant Park – once the domain of drug dealers and other such undesirables – into Manhattan’s premier address without using public coffers.

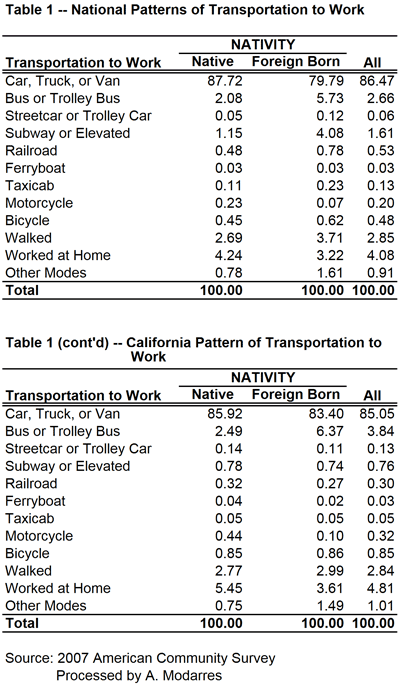

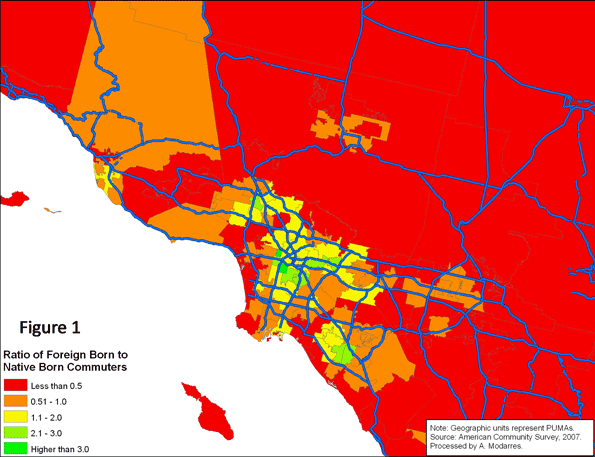

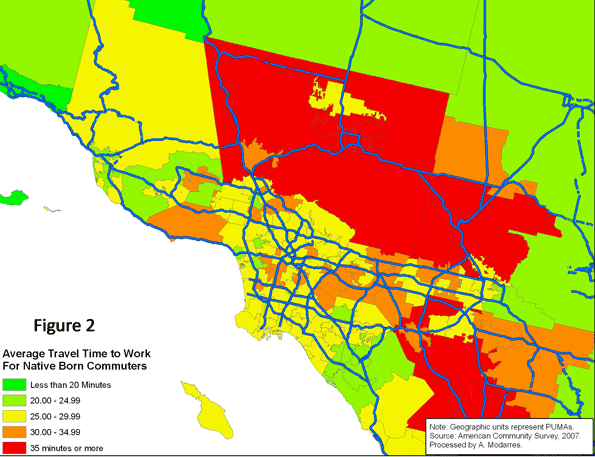

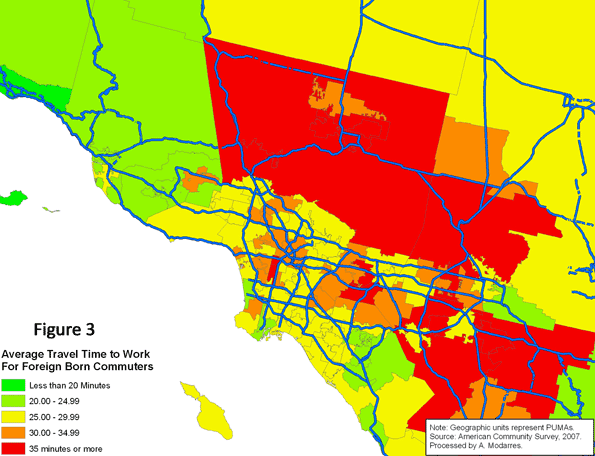

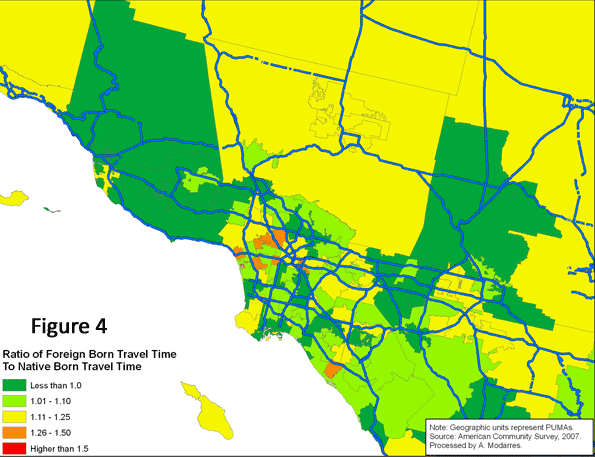

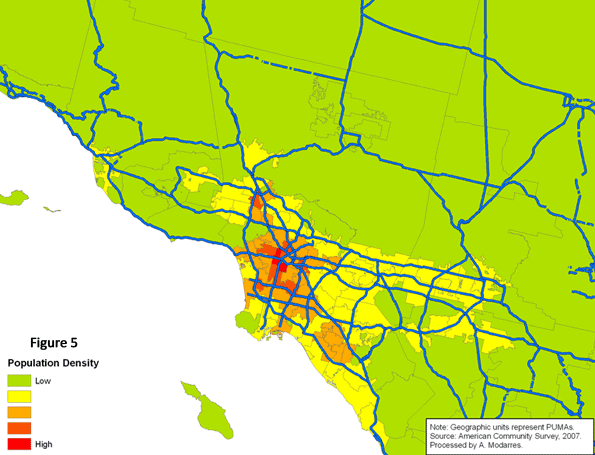

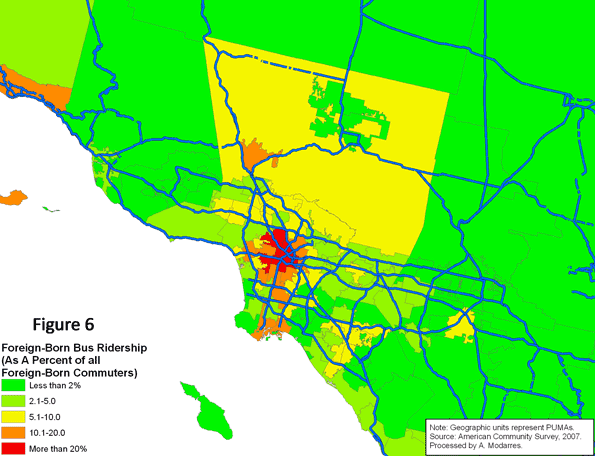

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

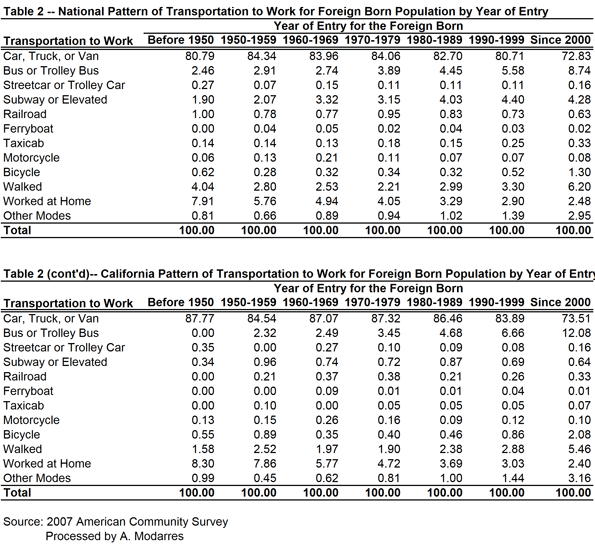

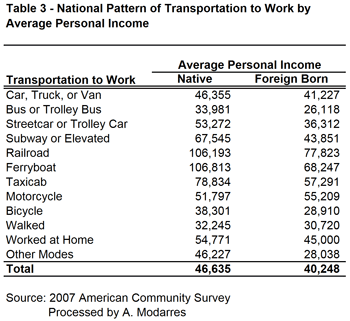

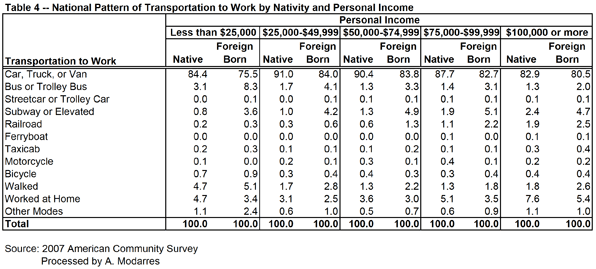

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.

Yet physical public space continues to serve as medium of the new Street Art form. Stickers, tags, skateboards, and tattoos are all viewed on the street, offering a means to carry this new art form into the next century. The so-called “cutting edge” artists have retreated into their private studios to conceive their next moves in video or computers, but the street artists have taken over the city.

Yet physical public space continues to serve as medium of the new Street Art form. Stickers, tags, skateboards, and tattoos are all viewed on the street, offering a means to carry this new art form into the next century. The so-called “cutting edge” artists have retreated into their private studios to conceive their next moves in video or computers, but the street artists have taken over the city.

Graffiti’s barrage of skulls, vacant-eyed cartoon children, and other signs of death and destruction are easy to ignore, but they are telling us something important about the urban environment. The sooner we stop and examine this evidence, the sooner we can begin a process to find common ground, and to seek out a shared vision that does not divide the urban world into an us-and-them mentality. Street art simply puts visual form to the voices we have so long shut out of the urban conversation.

Graffiti’s barrage of skulls, vacant-eyed cartoon children, and other signs of death and destruction are easy to ignore, but they are telling us something important about the urban environment. The sooner we stop and examine this evidence, the sooner we can begin a process to find common ground, and to seek out a shared vision that does not divide the urban world into an us-and-them mentality. Street art simply puts visual form to the voices we have so long shut out of the urban conversation.

The graffiti artists have offered a philosophical change-up that should not be overlooked. The conversation about postmodern art seemed to have reached a dead end some time ago; artists

The graffiti artists have offered a philosophical change-up that should not be overlooked. The conversation about postmodern art seemed to have reached a dead end some time ago; artists