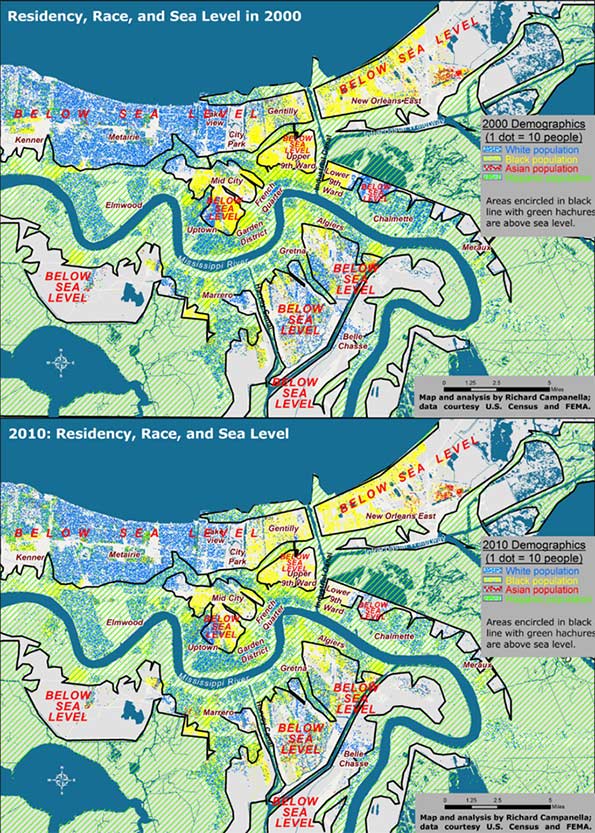

Urban risk may be understood as a function of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability.1 In metro New Orleans, Katrina-like storm surges constitute the premier hazard (threat); the exposure variable entails human occupancy of hazard-prone spaces; and vulnerability implies the ability to respond resiliently and adaptively—which itself is a function of education, income, age, social capital, and other factors—after having been exposed to the hazard.

This essay measures the extent to which, after the catastrophic deluge triggered by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, residents of metro New Orleans have shifted their settlement patterns and how these movements may affect future urban risk.2 What comes to light is that, at least in terms of residential settlement geographies, the laissez faire rebuilding strategy for flooded neighborhoods proved to be exactly that.

“The Great Footprint Debate” of 2005-2006

An intense debate arose in late 2005 over whether low-lying subdivisions heavily damaged by Katrina’s floodwaters should be expropriated and converted to greenspace. Most citizens and nearly all elected officials decried that residents had a right to return to all neighborhoods. Planners and experts countered by explaining that a population living in higher density on higher ground and surrounded by a buffer of surge-absorbing wetlands would be less exposed to future storms, and would achieve a new level of long-term sustainability.

Despite its geophysical rationality, “shrinking the urban footprint” proved to be socially divisive, politically volatile, and ultimately unfunded. Officials thus had little choice but to abrogate the spatial oversight of the rebuilding effort to individual homeowners, who would return and rebuild where they wished based on their judgment of a neighborhood’s viability.

Federal programs nudged homeowners to return to status quo settlement patterns. Updated flood-zone maps from FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program, for example, would provide actuarial encouragement to resettle in prediluvial spaces, while the federally funded, state-administered Louisiana Road Home Program’s “Option 1”—to rebuild in place, by far the most popular of the three options—provided grant money to do exactly that.

“Shrinking the urban footprint” became heresy; “greenspacing” took on sinister connotations; and rebuilding in flooded areas came to be valorized as a heroic civic statement. Actor Brad Pitt’s much-celebrated Make It Right Foundation, for example, pointedly positioned its housing initiative along a surge-prone canal, below sea level and immediately adjacent to the single worst Katrina levee breach, to illustrate that if a nonprofit “could build safe, sustainable homes in the most devastated part of New Orleans, [then it] would prove that high-quality, green housing could be built affordably everywhere.”3 Ignoring topography and hydrology gained currency in the discourse of community sustainability even as it flew in the face of environmental sustainability.

A Brief History of New Orleans’ Residential Settlement Patterns, 1718-2005

Topography and hydrology have played fundamental roles in determining where New Orleanians settled since the city’s founding in 1718. The entire region, lying at the heart of the dynamic deltaic plain of the Mississippi River, originally lay above sea level, ranging from a few inches along the marshy perimeter, to a few feet along an interior ridge system, to 8 to 12 feet along the natural levee abutting the Mississippi River.

From the 1700s to the early 1900s, the vast majority of New Orleanians lived on the higher ground closer to the Mississippi. Uninhabited low-lying backswamps, while reviled for their (largely apocryphal) association with disease, nonetheless provided a valuable ecological service for city dwellers, by storing excess river or rain water and safeguarding the city from storm surges. Even the worst of the Mississippi River floods, in 1816, 1849, and 1871, mostly accumulated harmlessly in empty swamplands and, in hindsight, bore more benefits than costs. New Orleanians during the 1700s-1900s were less exposed to the hazard of flooding because the limitations of their technology forced them to live on higher ground.4

Circumstances changed in the 1890s, when engineers began designing and installing a sophisticated municipal drainage system to enable urbanization to finally spread across the backswamp to the Gulf-connected brackish bay known as Lake Pontchartrain. A resounding success from a developmental standpoint, the system came with a largely unforeseen cost. As the pumps removed a major component of the local soil body—water— it opened up cavities, which in turn allowed organic matter (peat) to oxidize, shrink, and open up more cavities. Into those spaces settled finely textured clay, silt, and sand particles; the soil body thus compacted and dropped below sea level. Over the course of the twentieth century, former swamps and marshes in places like Lakeview, Gentilly, and New Orleans East sunk by 6-10 feet, while interior basins such as Broadmoor dropped to 5 feet below sea level. New levees were built along the lakefront, and later along the lateral flanks, were all that prevented outside water from pouring into the increasingly bowl-shaped metropolis.

Nevertheless, convinced that the natural factors constraining their residential options had now been neutralized, New Orleanians migrated enthusiastically out of older, higher neighborhoods and into lower, modern subdivisions. Between 1920 and 1930, nearly every lakeside census tract at least doubled in population; low-lying Lakeview increased by 350 percent, while parts of equally low Gentilly grew by 636 percent. Older neighborhoods on higher ground, meanwhile, lost residents: Tremé and Marigny dropped by 10 to 15 percent, and the French Quarter declined by one-quarter. The high-elevation Lee Circle area lost 43 percent of its residents, while low-elevation Gerttown increased by a whopping 1,512 percent.5

The 1960 census recorded the city’s peak of 627,525 residents, double the population from the beginning of the twentieth century. But while nearly all New Orleanians lived above sea level in 1900, only 48 percent remained there by 1960; fully 321,000 New Orleanians had vertically migrated from higher to lower ground, away from the Mississippi River and northwardly toward the lake as well as into the suburban parishes to the west, east, and south.6

Subsequent years saw additional tens of thousands of New Orleanians migrate in this pattern, motivated at first by school integration and later by a broader array of social and economic impetuses. By 2000, the Crescent City’s population had dropped by 23 percent since 1960, representing a net loss of 143,000 mostly middle-class white families to adjacent parishes. Of those that remained, only 38 percent lived above sea level.7

Meanwhile, beyond the metropolis, coastal wetlands eroded at a pace that would reach 10-35 square miles per year, due largely to two main factors: (1) the excavation through delicate marshes of thousands of miles of erosion-prone, salt-water-intruding navigation and oil-and-gas extraction canals, and (2) the leveeing of the Mississippi River, which prevented springtime floods but also starved the delta of new fresh water and vital sediment. Gulf waters crept closer to the metropolis’ floodwalls and levees, while inside that artificial perimeter of protection, land surfaces that once sloped gradually to the level of the sea now formed a series of topographic bowls straddling sea level.

When those floodwalls and levees breached on August 29, 2005, sea water poured in and became impounded within those topographic bowls, a deadly reminder that topography still mattered. Satellite images of the flood eerily matched the shape of the undeveloped backswamp in nineteenth-century maps, while those higher areas that were home to the historical city, quite naturally, remained dry.

But the stark geo-topographical history lesson could only go so far in convincing flood victims to move accordingly; after all, they still owned their low-lying properties, and real estate on higher terrain was anything but cheap and abundant. Besides, New Orleanians in general rightfully felt that they had been scandalously wronged by federal engineering failures, and anything short of full metropolitan reconstitution came to be seen as defeatist and unacceptable. Most post-Katrina advocacy thus focused on reinforcing the preexisting technological solutions that kept water out of the lowlands, rather than nudging people toward higher ground. “Shrink the urban footprint” got yelled off the table; “Make Levees, Not War” and “Category-5 Levees Now!” became popular bumper-sticker slogans; and “The Great Footprint Debate” became a bad memory.

Resettlement in Vertical Space

The early repopulation of post-Katrina New Orleans defied easy measure. Residents living “between” places as they rebuilt, plus temporarily broken-up families, peripatetic workers, and transient populations all conspired to make the city’s 2006-2009 demographics difficult to estimate, much less map. The 2010 Census finally provided a precise number: 343,829. By 2014, over 384,000 people lived in Orleans Parish, or eighty percent of the pre-Katrina figure. Of course, not all were here prior; one survey determined roughly 10 percent of the city’s postdiluvian population had not lived here before 2005.8

How had the new population resettled in terms of topographic elevation? We won’t know precisely until 2020, because only the decennial census provides actual headcounts aggregated at sufficiently high spatial resolution (the block level) for this sort of analysis; annual estimates from the American Community Survey do not suffice. Thus we must make do with the 2010 Census. While much has changed during 2010-2015, the macroscopic settlement geographies under investigation here had largely had fallen into place by 2010.

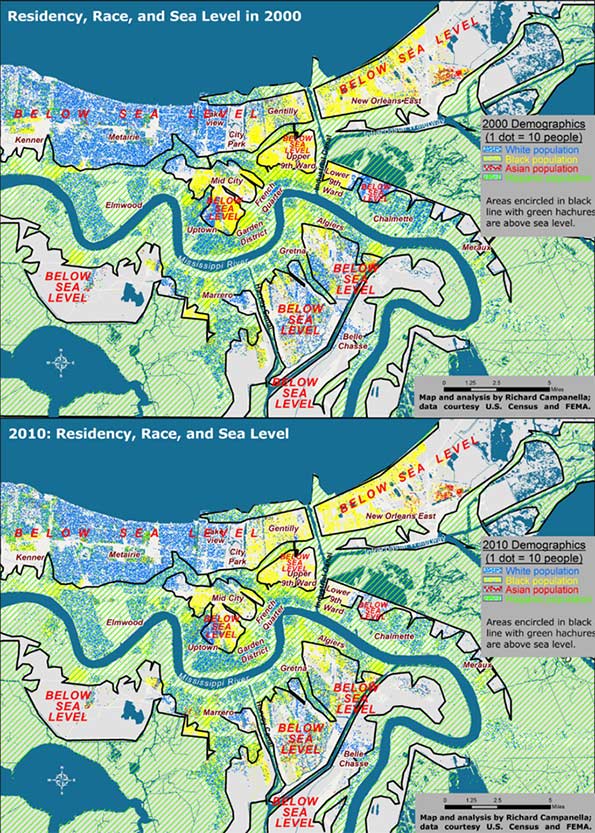

Figure 1. Residential settlement above and below sea level, 2000 and 2010; analysis and maps by Richard Campanella.

When intersected with high-resolution LIDAR-based digital elevation models, the 2010 Census data show that residents of metro New Orleans shifted to higher ground by only 1 percent compared to 2000 (Figure 1). Whereas 38 percent of metro-area residents lived above sea level in 2000, 39 percent did so by 2010, and that differentiation generally held true for each racial and ethnic group. Whites shifted from 42 to 44 percent living above sea level; African Americans 33 to 34 percent, Hispanics from 30 to 29 percent, and Asians 20 to 22 percent.

Clearly, elevation did not exercise much influence in resettlement decisions, and people distributed themselves in vertical space in roughly the same proportions as before the flood. Yet there is one noteworthy angle to the fact that the above-sea-level percentage has risen, albeit barely (38 to 39 percent): it marked the first time in New Orleans history that the percent of people living below sea level has actually dropped.

What impact did the experience of flooding have on resettlement patterns? Whereas people shifted only slightly out of low-lying areas regardless of flooding, they moved significantly out of areas that actually flooded, regardless of elevation. Inundated areas lost 37 percent of their population between 2000 and 2010, with the vast majority departing after 2005. They lost 37 percent of their white populations, 40 percent of their black populations, and 10 percent of their Asian populations. Only Hispanics increased in the flooded zone, by 10 percent, in part because this population had grown dramatically region-wide, and because members of this population sometimes settled in neighborhoods they themselves helped rebuild.

The differing figures suggest that while low-lying elevation theoretically exposes residents to the hazard of flooding, the trauma of actually flooding proved to be, sadly, much more convincing.

Resettlement in Horizontal Space

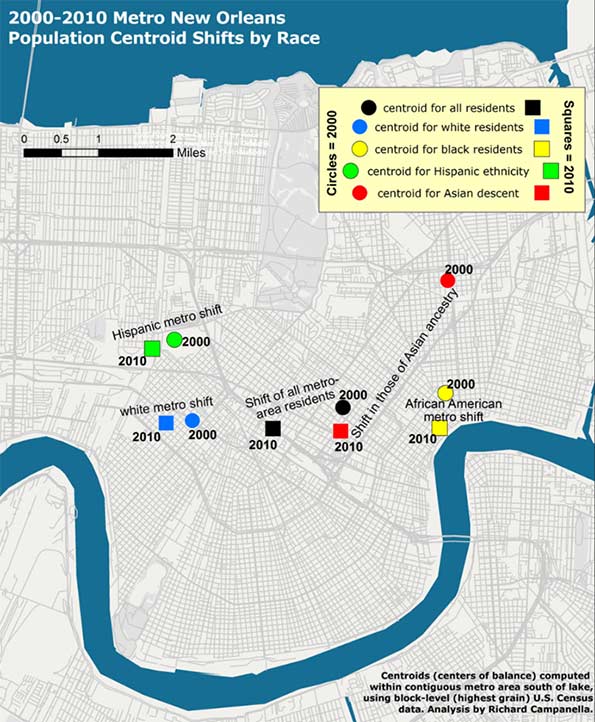

Contrasting before-and-after residential patterns in horizontal space may be done through traditional methods such as comparative maps and demographic tables. What this investigation offers is a more singular and synoptical depiction of spatial shifts: by computing and comparing spatial central tendencies, or centroids.

A centroid is a theoretical center of balance of a given spatial distribution. A population centroid is that point around which people within a delimited area are evenly distributed.9

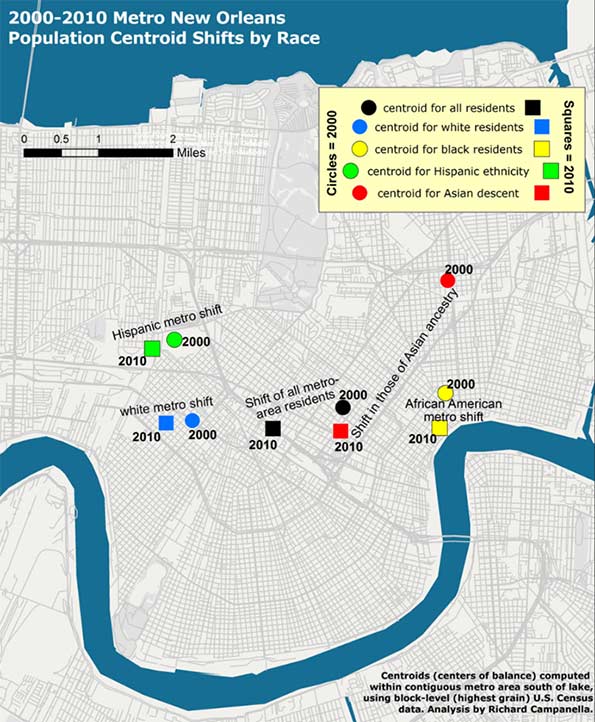

Centroids capture complex shifts of millions of data with a single point. But they do not tell the entire story. A centroid for a high-risk coastal area, for example, may shift inland not because people have moved away from the seashore, but because previous residents decided not to return there. It’s also worth noting it takes a lot to move a centroid, as micro-scale shifts in one area are usually offset by countervailing shifts elsewhere. Thus, apparent minor centroid movements can actually be significant. Following are the centroid shifts for metro New Orleans broken down by racial and ethnic groups (Figures 2 and 3).

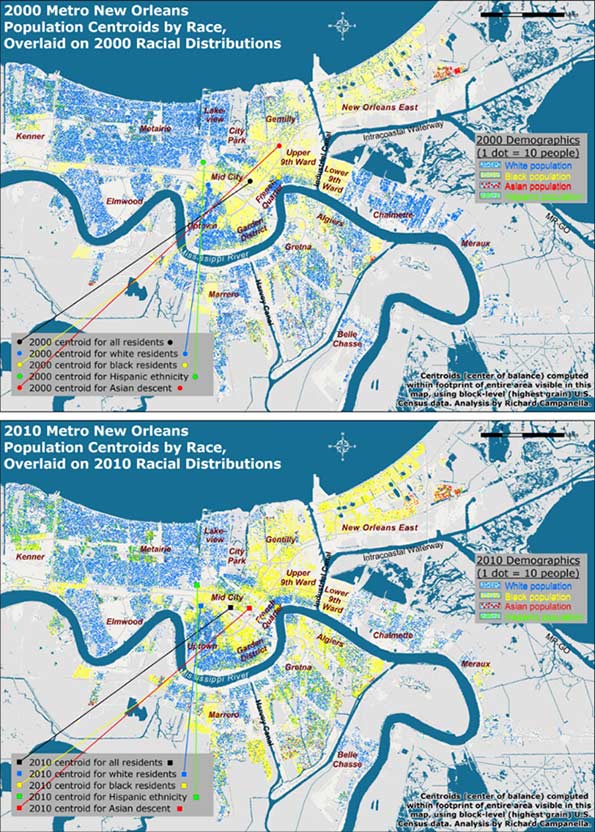

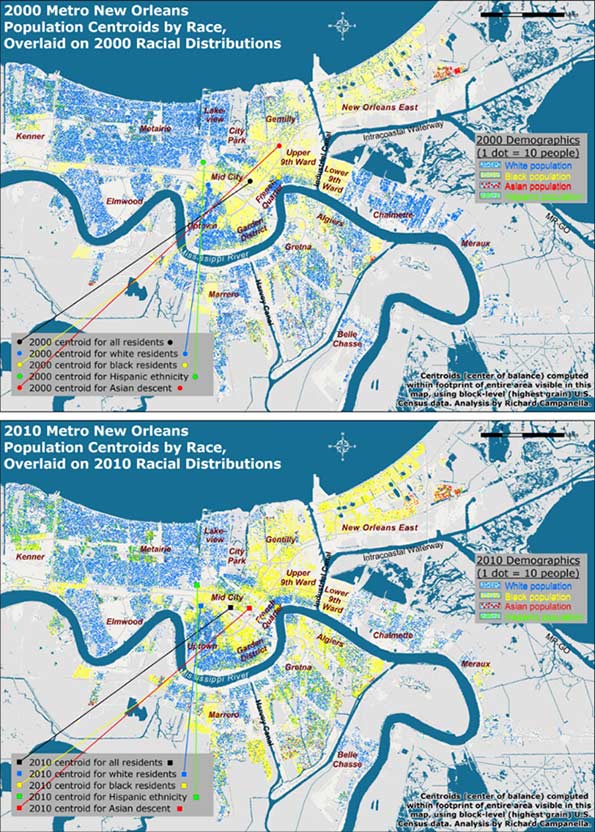

In 2000, five years before the flood, there were 1,006,783 people living within the metro area as delineated for this particular study, of whom 512,696 identified their race as white; 435,353 as black; 25,941 as Asian; and 50,451 as Hispanic in ethnicity. Five years after the flood, these figures had changed to 817,748 total population, of whom 416,232 were white; 327,972 were black; 27,562 were Asian, and 75,397 were Hispanic.10 When their centroids are plotted, they show that metro residents as a whole, and each racial/ethnic sub-group, shifted westward and southward between 2000 and 2010, away from the location of most of the flooding and away from the source of most of the surge, which generally penetrated the eastern and northern (lakeside) flanks of the metropolis.

Did populations proactively move away from risk? Not quite. What accounts for these shifts is the fact that the eastern half of the metropolis bore the brunt of the Katrina flooding, and the ensuing destruction meant populations here were less likely to reconstitute by 2010, which thus nudged centroids westward. Additionally, flooding from Lake Pontchartrain through ruptures in two of the three outfalls (drainage) canals disproportionally damaged the northern tier of the city, namely Lakeview and Gentilly. Combined with robust return rates in the older, higher historical neighborhoods along the Mississippi, as well as the unflooded West Bank (which sit to the south and west of the worst-damaged areas), they abetted a southwestward shift of the centroids. In a purely empirical sense, this change means more people now live in less-exposed areas. But, as we saw with the vertical shifts, the movements are more a reflection of passive responses to flood damage than active decisions to avoid future flooding.

Figure 2. Population centroids by race and ethnicity for metro New Orleans, 2000-2010; see next figure for detailed view. Analysis and maps by Richard Campanella.

Figure 3. A closer look at the metro-area population centroid shifts by race and ethnicity, 2000-2010; analysis and map by Richard Campanella.

Reflections

Resettlement patterns in metro New Orleans have only marginally reduced residential exposure to the hazard of storm surge. In the vertical dimension, metro-area residents today occupy below-sea-level areas at only a slightly lower rate than before the deluge, 61 percent as opposed to 62 percent, although that change represents the first-ever reverse (decline) of the century-long drift into below-sea-level areas. Likewise, residents’ horizontal shifts, which were in southwestward directions, seemed to suggest a movement away from hazard, but these shifts were more a product of passive than active processes .

Metro New Orleans, it is important to note, has substantially reduced its overall risk—but mostly thanks to its new and improved federal Hurricane & Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS) rather than shifts in residences. No longer called a “protection” system, the Risk Reduction System is a $14.5 billion integrated network of raised levees, strengthened floodwalls, barriers, gates, and pumps built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its contractors to protect the metropolis from the surges accompanying storms with a 1-percent chance of occurring in any given year.11 The HSDRRD, which worked well during Hurricane Isaac’s surprisingly strong surge in 2012, has given the metropolis a new lease on life, at least for the next few decades. But all other risk drivers—the condition of the coastal wetlands, subsidence and sea level rise, social vulnerability, and, as evidenced in this paper, exposure—have either slightly worsened, only marginally improved, or generally remained constant.

The exposure-related patterns reported here reflect who won the “Great Footprint Debate” ten years ago.12 Months after Katrina, when it became clear that no neighborhoods would be closed and the urban footprint would persist, decisions driving resettlement patterns in the flooded region effectively transferred from leaders to homeowners. Rather inevitably, the laissez faire rebuilding strategy proved to be exactly that, and people generally repopulated areas they had previously occupied, though at markedly varied densities.

Ten years later, the resulting patterns are a veritable Rorschach Test. Some observers look to the 75-90 percent repopulation rates of certain flooded neighborhoods and view them as heroically high, proof of New Orleanians’ resilience and love-of-place. Others point to the 25-50 percent rates of other areas and call them scandalously low, evidence of corruption and ineptitude. Still others might point to the thousands of scattered blighted properties and weedy lots and concede—as St. Bernard Parish President David Peralta admitted on the ninth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina—that “we probably should have shrunk the footprint of the parish at the very beginning.”13

As for the HSDRRS, continual subsidence and erosion vis-à-vis rising seas, coupled with costly and as-yet undetermined maintenance and certification responsibilities, will gradually diminish the safety dividend provided by this remarkable system. The nation’s willingness to pay for continued upkeep, meanwhile, may grow tenuous; indeed, it’s not even a safe bet locally. Voters in St. Bernard Parish, which suffered near-total inundation from Katrina, defeated not once but twice a tax to pay for drainage and levee maintenance, a move that may well increase flood insurance rates.14

Residents throughout the metropolis appear to be repeating the same mistakes they made during the twentieth century: of dismissing the importance of natural elevation, of over-relying on engineering solutions, of under-maintaining these structures in a milieu of scarce funds, and of developing a false sense of security about flood “protection.”

We need to recognize the limits of our ability to neutralize hazards—that is, to presume that levees will completely protect us from storm surges—while appreciating the benefits of reducing our exposure to them. Beyond the metropolis, this means aggressive coastal restoration using every means available as soon as possible, an effort that may well require some expropriations. Within the metropolis, it means living on higher ground or otherwise mitigating risk. In the words of University of New Orleans disaster expert Dr. Shirley Laska, “mitigation, primarily elevating houses, is [one] way to achieve the affordable flood insurance…. It is possible to remain in moderately at-risk areas using engineered mitigation efforts, combined with land use planning that restricts development in high-risk areas.”15

Planning that restricts development in high-risk areas: this was the same reasoning behind the “shrink the urban footprint” argument of late 2005—and anything but the laissez faire strategy that ensued.

Bio

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of “Bienville’s Dilemma,” “Geographies of New Orleans,” “Delta Urbanism,” “Bourbon Street: A History,” and other books. His articles may be read at http://richcampanella.com , and he may be reached at rcampane@tulane.edu or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Gulf of Mexico Program Officer Kristin Tracz of the Walton Family Foundation, Dr. Shirley Laska, and the Gulf Coast Restoration Fund at New Venture Fund, and Tulane School of Architecture, as well as Garry Cecchine, David Johnson, and Mark Davis for their reviews.

1 David Crichton, “The Risk Triangle,” in Natural Disaster Management, edited by J. Ingleton (Tudor Rose, London, 1999), pp. 102-103.

2 In this paper, “metro New Orleans” means the conurbation (contiguous urbanized area shown in the maps) of Orleans, Jefferson, western St. Bernard, and upper Plaquemines on the West Bank (Belle Chasse); it excludes the outlying rural areas of these parishes, such as Lake Catherine, Grand Island, and Hopedale, and does not include the North Shore or the river parishes.

4 Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans and Geographies of New Orleans (University of Louisiana Press, 2006, 2008); R. Campanella, Delta Urbanism: New Orleans (American Planning Association, 2010); R. Campanella, “The Katrina of the 1800s Was Called Sauve’s Crevasse,” Times-Picayune, June 13, 2014, and other prior works by the author.

5 H. W. Gilmore, Some Basic Census Tract Maps of New Orleans (New Orleans, 1937), map book stored at Tulane University Special Collections, C5-D10-F6.

6 Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (University of Louisiana Press, 2008) and other prior works by the author.

7 Coincidently, 38 percent of all residents of the contiguous metropolis south of Lake Pontchartrain also lived above sea level in 2000. Thus, at both the city and metropolitan level, three out of every eight residents lived above sea level and the other five resided below sea level. All figures calculated by author using highest-grain available historical demographic data, usually from the U.S. Census, and LIDAR-based high-resolution elevation data captured in 1999-2000 by FEMA and the State of Louisiana.

9 Defining the study area is essential when reporting centroids. New Orleans proper, the contiguous metro area, and the Metropolitan Statistical Area, which includes St. Tammany and other outlying parishes, would all have different population centroids. This study uses the metro area south of the lake shown in the accompanying maps. It is also important to use the finest-grain—that is, highest spatial resolution—demographic data to compute centroids, as coarsely aggregated data carries with it a wider margin of error. This study uses block-level data from the decennial U.S. Census, the finest available.

10 Figures do not sum to totals because some people chose two or more racial categories while others declined the question, and because Hispanicism is viewed by the Census Bureau as an ethnicity and not a race.

12 Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (University of Louisiana Press, 2008), pp. 344-355.

13 David Peralta, as quoted by Benjamin Alexander-Bloch, “Hurricane Katrina +9: Smaller St. Bernard Parish Grappling with Costs of Coming Back,” Times-Picayune/NOLA.COM, August 29, 2014.

14 Mark Schleifstein, “St. Bernard Tax Defeat Means Higher Flood Risk, Flood Insurance Rates, Levee Leaders Warn,” Times-Picayune/NOLA.COM, May 4, 2015, http://www.nola.com/environment/index.ssf/2015/05/st_bernard_tax_defeat_means_hi.html ; see also Richard Campanella, “The Great Footprint Debate, Updated,” Times-Picayune/NOLA.COM, May 31, 2015.

15 Shirley Laska, email communication with author, April 12, 2015.

The next culture war will not be about issues like gay marriage or abortion, but about something more fundamental: how Americans choose to live. In the crosshairs now will not be just recalcitrant Christians or crazed billionaire racists, but the vast majority of Americans who either live in suburban-style housing or aspire to do so in the future. Roughly four in five home buyers prefer a single-family home, but much of the political class increasingly wants them to live differently.

Theoretically, the suburbs should be the dominant politically force in America. Some 44 million Americans live in the core cities of America’s 51 major metropolitan areas, while nearly 122 million Americans live in the suburbs. In other words, nearly three-quarters of metropolitan Americans live in suburbs.

Yet it has been decided, mostly by self-described progressives, that suburban living is too unecological, not mention too uncool, and even too white for their future America. Density is their new holy grail, for both the world and the U.S. Across the country efforts are now being mounted—through HUD, the EPA, and scores of local agencies—to impede suburban home-building, or to raise its cost. Notably in coastal California, but other places, too, suburban housing is increasingly relegated to the affluent.

The obstacles being erected include incentives for density, urban growth boundaries, attempts to alter the race and class makeup of communities, and mounting environmental efforts to reduce sprawl. The EPA wants to designate even small, seasonal puddles as “wetlands,” creating a barrier to developers of middle-class housing, particularly in fast-growing communities in the Southwest. Denizens of free-market-oriented Texas could soon be experiencing what those in California, Oregon and other progressive bastions have long endured: environmental laws that make suburban development all but impossible, or impossibly expensive. Suburban family favorites like cul-de-sacs are being banned under pressure from planners.

Some conservatives rightly criticize such intrusive moves, but they generally ignore how Wall Street interests and some developers see forced densification as opportunities for greater profits, often sweetened by public subsidies. Overall, suburban interests are poorly organized, particularly compared to well-connected density lobbies such as the developer-funded Urban Land Institute (ULI), which have opposed suburbanization for nearly 80 years.

The New Political Logic

The progressives’ assault on suburbia reflects a profound change in the base of the Democratic Party. As recently as 2008, Democrats were competitive in suburbs, as their program represented no direct threat to residents’ interests. But with the election of Barack Obama, and the continued evolution of urban centers as places with little in the way of middle-class families, the left has become increasingly oriented towards dense cities, almost entirely ruled by liberal Democrats.

Obama’s urban policies are of a piece with those of “smart growth” advocates who want to curb suburban growth and make sure that all future development is as dense as possible. Some advocate radical measures such as siphoning tax revenues from suburbs to keep them from “cannibalizing” jobs and retail sales. Some even fantasize about carving up the suburban carcass, envisioning three-car garages “subdivided into rental units with street front cafés, shops and other local businesses” while abandoned pools would become skateboard parks.

At the end of this particular progressive rainbow, what will we find? Perhaps something more like one sees in European cities, where the rich and elite cluster in the center of town, while the suburbs become the “new slums” that urban elites pass over on the way to their summer cottages.

Political Dangers

The abandonment of the American Dream of suburban housing and ownership represents a repudiation of what Democrats once embraced and for which millions, including many minorities, continue to seek out. “A nation of homeowners,” Franklin D. Roosevelt asserted, “of people who own a real share in their land, is unconquerable.”

This rhetoric was backed up by action. It was FDR, and then Harry Truman, who backed the funding mechanisms—loans for veterans, for example—that sparked suburbia’s growth. Unlike today’s progressives, the old school thought it good politics to favor those things that most people aspire to achieve. Democrats gained ground in the suburbs, which before 1945 had been reliably and overwhelmingly Republican.

Even into the 1980s and beyond, suburbanites functioned less as a core GOP constituency than as the ultimate swing voters. As urban cores became increasingly lock-step liberal, and rural Democrats slowlyfaded towards extinction, the suburbs became the ultimate contested territory. In 2006, for example, Democrats won the majority of suburban voters. In 2012, President Obama did less well than in 2008, but still carried most inner and mature suburbs while Romney trounced him in the farther out exurbs. Overall Romney eked out a small suburban margin.

Yet by 2014, as the Democratic Party shifted further left and more urban in its policy prescriptions, these patterns began to turn. In the 2014 congressional elections, the GOP boosted its suburban edge to 12 percentage points. The result was a thorough shellacking of the Democrats from top to bottom.

Will demographics lead suburbs to the Democrats?

Progressive theory today holds that the 2014 midterm results were a blast from the suburban past, and that the key groups that will shape the metropolitan future—millennials and minorities—will embrace ever-denser, more urbanized environments. Yet in the last decennial accounting, inner cores gained 206,000 people, while communities 10 miles and more from the core gained approximately 15 million people.

Some suggest that the trends of the first decade of this century already are passé, and that more Americans are becoming born-again urbanistas. Yet after a brief period of slightly more rapid urban growth immediately following the recession, U.S. suburban growth rates began to again surpass those of urban cores. An analysis by Jed Kolko, chief economist at the real estate website Trulia, reports that between 2011 and 2012 less-dense-than-average Zip codes grew at double the rate of more-dense-than-average Zip codes in the 50 largest metropolitan areas. Americans, he wrote, “still love the suburbs.”

What is also missed by the Obama administration and its allies is the suburbs’ growing diversity. If HUD wants to start attacking these communities, many of their targets will not be whites, but minorities, particularly successful ones, who have been flocking to suburbs for well over a decade.

This undermines absurd claims that the suburbs need to be changed in order to challenge the much detested reign of “white privilege.” In reality, African-Americans have been deserting core cities for years, largely of their own accord and through their own efforts: Today, only 16 percent of the Detroit area’s blacks live within the city limits.

These trends can also be seen in the largely immigrant ethnic groups. Roughly 60 percent of Hispanics and Asians, notes the Brooking Institution, already live in suburbs. Between the years 2000 and 2012, the Asian population in suburban areas of the nation’s 52 biggest metro areas grew by 66 percent, while that in the core cities expanded by 35 percent. Of the top 20 areas with over 50,000 in Asian population, all but two are suburbs.

Left to market forces and natural demographic trends, suburbs are becoming far more diverse than many cities, meaning that in turning on suburbia, progressives are actually stomping on the aspirations not just of privileged whites but those of many minorities who have worked hard to get there.

Another huge misreading of trends relates to another key Democratic constituency, the millennial generation. Some progressives have embraced the dubious notion that millennials won’t buy cars or houses, and certainly won’t migrate to the suburbs as they marry and have families. But those notions are rapidly dissolving as millennials do all those things. They are even—horror of horrors!—shopping atWal-Mart, and in greater percentages than older cohorts.

Moreover, notes Kolko, millennials are not moving to the denser inner ring suburban areas. They are moving to the “suburbiest” communities, largely on the periphery, where homes are cheaper, and often schools are better. When asked where their “ideal place to live,” according to a survey by Frank Magid and Associates, more millennials identified suburbs than previous generations. Another survey in the same year, this one by the Demand Institute, showed similar proclivities.

Stirrings of Rebellion

So if the American Dream is not dead among the citizens, is trying to kill it good politics? It’s clear that Democratic constituencies, notably millennials, immigrants and minorities, and increasingly gays—particularly gay couples—are flocking to suburbs. This is true even in metropolitan San Francisco, where 40 percent of same-sex couples live outside the city limits.

One has to wonder how enthusiastic these constituents will be when their new communities are “transformed” by federal social engineers. One particularly troubling group may be affluent liberals in strongholds such as Marin County, north of San Francisco, long a reliable bastion of progressive ideology.

Forced densification–the ultimate goal of the “smart growth” movement—also has inspired opposition in Los Angeles, where densification is being opposed in many neighborhoods, as well as traditionally more conservative Orange Country. Similar opposition has arisen in Northern Virginia suburbs, another key Democratic stronghold.

These objections may be dismissed as self-interested NIMBYism, but this misses the very point about why people move to suburbs in the first place. They do so precisely in to avoid living in crowded places. This is not anti-social, as is alleged, but an attempt—natural in any democracy—to achieve a degree of self-determination, notes historian Nicole Stelle Garrett.

Aroused by what they perceive as threats to their preferred way of life, these modern pilgrims can prove politically effective. They’ve shown this muscle while opposing plans not only to increase the density in suburbs, and also balking at the shift of transportation funding from roads, which suburbanites use heavily, to rail transit. This was seen in Atlanta in 2012 when suburban voters rejected a mass transit plan being pushed by downtown elites and their planning allies. Opposition to expanding rail service has also surfaced in the Maryland suburbs of Washington.

Suburbs and 2016 Election

To justify their actions against how Americans prefer to live, progressives will increasingly cite the environment. Climate change has become the “killer app” in the smart growth agenda and you can expect the drumbeat to get ever louder towards the Paris climate change conference this summer.

Yet the connection between suburbs and climate is not as clear as the smart growth crowd suggests. McKinsey and other studies found no need to change housing patterns to reduce greenhouse gases, particularly given improvements in both home and auto efficiency. Yet so great is their animus that many anti-suburban activists seem to prefer stomping on suburban aspirations rather seeking ways to make them more environmental friendly.

As for the drive to undermine suburbs for reasons of class, in many ways the assault on suburbia is, in reality, a direct assault on our most egalitarian geography. An examination of American Community Survey Data for 2012 by the University of Washington’s Richard Morrill indicates that the less dense suburban areas tended to have “generally less inequality” than the denser core cities; Riverside-San Bernardino, for example, is far less unequal than Los Angeles; likewise, inequality is less pronounced in Sacramento than San Francisco. Within the 51 metropolitan areas with more than 1 million people, notes demographer Wendell Cox, suburban areas were less unequal (measured by the GINI Coefficient) than the core cities in 46 cases.

In the coming year, suburbanites should demand more respect from Washington, D.C., from the media, the political class and from the planning community. If people choose to move into the city, or favor density in their community, fine. But the notion that it is the government’s job to require only one form of development contradicts basic democratic principles and, in effect, turns even the most local zoning decision into an exercise in social engineering.

As America’s majority, suburbanites should be able to deliver a counterpunch to those who seem determined to destroy their way of life. Irrespective of race or generation, those who live in the suburbs—or who long to do so—need to understand the mounting threat to their aspirations Once they do, they could spark a political firestorm that could reshape American politics for decades to come.

This piece first appeared at Real Clear Politics.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Suburbs photo courtesy of BigStockPhoto.com.

Travis Estell UrbanCincy

Travis Estell UrbanCincy Travis Estell UrbanCincy

Travis Estell UrbanCincy Travis Estell UrbanCincy

Travis Estell UrbanCincy