In the fall of 2005, many saw in postdiluvial New Orleans another example of failed urbanization, a formerly great city that was broken beyond repair.Yet 10 years after a catastrophe that drove hundreds of thousands of its citizens away, the metro area has made an impressive comeback.

New Orleans’ resurgence since Katrina has come courtesy of $71 billion in federal funds and the determination and verve of New Orleanians themselves, as documented by Tulane geographer Rich Campanella, who provided research and direction for this article. It also benefited from the generosity of thevolunteers who worked in the recovery efforts as well as that of neighboring cities, notably Houston, which housed thousands of evacuees. Many have now returned, joined by newcomers from around the country, determined to turn around the city. “A city,” notes urban historian Kevin Lynch, “is hard to kill,” and New Orleans is proving that assertion.

New Orleans’ comeback reflects not only improved levees and disaster management planning but a break from the region’s famously corrupt politics. Author Joel Garreau once described the city as a “marvelous collection of sleaziness and peeling paint.” Today the metro area, and Louisiana, is earning higher marks for efficiency and business friendliness. In Forbes’ annual ranking of the Best States For Business, Louisiana has risen from dead last in 2006 to 29th place in 2014, while Chief Executive Magazine ranks the state as having the ninth best business climate in the country, up from 45th in 2008.

Perhaps most compelling has been the improvement in the public schools, which were once among the worst in the country. After the storm, most of the campuses were converted to charter schools, which now educate over 80% of the parish’s schoolchildren. New Orleans now outperforms not only the rest of the state but the nation in terms of high school graduation rates, which have risen to 73% in 2014 from 54% in 2004, and the percentage of students on grade level in grades 3-11 is at 68%, up from 25% in 2000. As Allison Plyer, executive director of the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, put it in 2013, “Greater New Orleans is in some ways rebuilding better than before.”

Growth, But Also A Rebound In Poverty

The improvements in governmental institutions have, along with federal aid, sparked something of a jobs boom in New Orleans. The metro area recovered all the jobs lost in the recession by 2012 while the nation remained 3% below its pre-recession level. The economy has expanded into some new sectors, such as digital media, while there has been a strong recovery in longtime core sectors liketourism and shipping, with an expansion of the port. After lagging the country for a generation, post-Katrina New Orleans surprised everyone by outperforming it.

But there are signs that New Orleans’ rate of growth is leveling out, as might be expected with the tailing off of federal recovery spending. In our annual ranking of the cities creating the most jobs, themetro area has dropped from 26th place in 2013 to 43rd. This slowdown could worsen the biggest challenge facing New Orleans: its historic legacy of poverty.

Greater New Orleans and the central city in particular have among the nation’s highest poverty rates and inequality. Even before Katrina, the city had over 26,000 blighted properties, a number that doubled after the storm.

As more evacuees have returned, poverty rates in the city and the metro area have resurged. Between 2007 and 2013 Orleans Parrish’s poverty rate rose from 21% to 27%, just about where it was in 1999. At the same time, the gap between white and African-American incomes and poverty rates remain well above the national averages. Incarceration rates in Orleans parish are almost four times as high as the national average, and the rest of the metro area also has incarceration rates considerably above the national average. New Orleans’ murder rate fell to the lowest level last year since 1971, but it was still the ninth highest among major U.S. cities.

A Demographic Resurgence

Yet some new demographic trends offer hope.Critically, the region finally has begun to reverse a demographic decline spanning more than a generation in which the urban core steadily lost young, educated people and families to the suburban periphery and beyond.

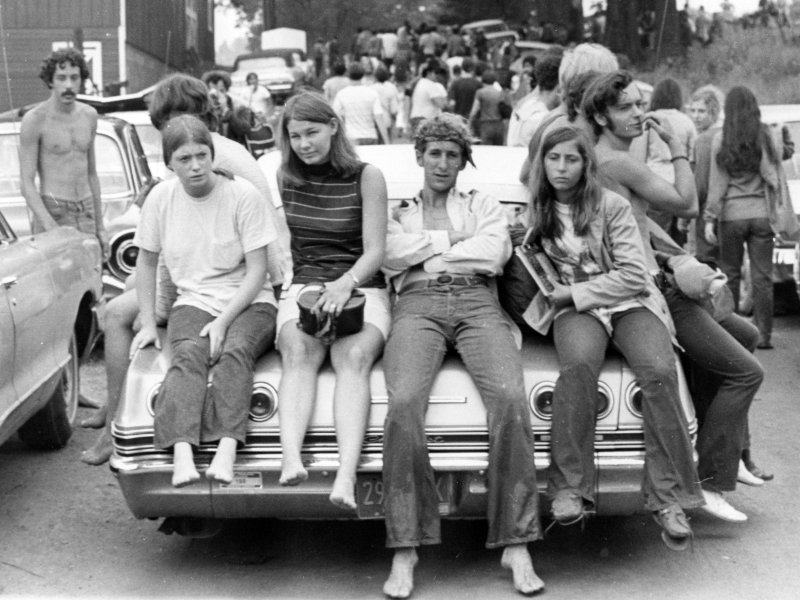

The immediate aftermath of Katrina saw an influx of “YURPS,” or Young Urban Rebuilding Professionals — urbanists, environmentalists and social workers who headed South to work in the recovery efforts, in nonprofits and government programs, seeking to be part of something important.After that came a wave of well-educated professionals, who saw personal opportunity in the region’s rebounding economy. Campanella estimate this latter group at around 15,000 to 20,000strong. Along with them, says Campanella, have come a fair number of artists, musicians, and creative types seeking to join in what they perceived to be an undiscovered bohemia in the lower faubourgs of New Orleans.

The New Orleans metro area’s population of college graduates increased by roughly 44,000 from 2007 to 2012, a 25% increase, double the national average of 12.2% over that span.

These educated newcomers are widely credited not only with helping rebuild New Orleans, but also sparking an increase in start-up companies well above the national pace and boosting the city’s economic diversification. Employment in the New Orleans area’s information sector — high-paying jobs in entertainment, games, software — grew 21.2% between 2007 and 2012, more than twice the national average, according to Praxis Strategy Group.

Is Gentrification A Threat?

This promising development, however, brings with it a set of problems, among them concern, particularly among African-Americans, about gentrification of inner-city neighborhoods. Many African-Americans, notes city employee Lydia Cutrer, have “trust issues after many broken promises, and feel like outsiders are taking over.” Or, as former New Orleanian Sherby Guillory, a health care worker and now a Houston resident put it acidly, “They want to build a shining city on a hill, but without the people.”

A map of the city by Campanella (below) shows where this turnover in population is the most advanced. He observes that the newcomers are attracted to a particular type of neighborhood – places with distinctive, historic housing stock, and close to areas that have already gentrified, or that never economically declined, like the Garden District. The arc of gentrification spreads through uptown New Orleans, around Audubon Park and Tulane and Loyola universities, with a curving spout along the St. Charles Avenue/Magazine Street corridor through the French Quarter and into the Faubourg Marigny and Bywater. These areas have in many cases been incubators of New Orleans’heavily African-American music and food culture, and now are losing some of those old connections.

Courtesy of Richard Campanella

As elsewhere gentrification is widely welcomed in the real estate and business communities, but also poses dilemmas, even for newcomers. Indeed gentrification threatens to undermine one of the very reasons young people are so attracted to New Orleans — its unique local culture. Boilerplate yuppie restaurants selling beet-filled ravioli is no substitute for fried okra and other traditional specialties.

The Physical Challenge Of Rebuilding

As Katrina demonstrated all too well, poverty in New Orleans is deeply intertwined with the geographic challenges of the region. Most predominately African-American neighborhoods were located in the low-lying areas of the city, easily susceptible to flooding, while more affluent, usually white neighborhoods were on higher ground.

Some have suggested moving the region’s entire population to higher ground, but political and fiscal realities, plus social resistance to closing down heavily damaged, far-flung neighborhoods, paved the way for resettlement patterns that have not reduced human exposure to the hazard of surge flooding.

But there’s no question that $14.5 billion in taxpayer dollars have gone to good use in keeping thosehazard at bay — at least for the next few decades. The Army Corps of Engineers’ new Hurricane Storm Surge Risk Reduction System — composed of heightened levees, floodwalls, surge barriers, gates, and pumps — now protects the metropolis from storms that have a 1% change of occurring in any given year. That’s much less than the city needs, but it’s a lot more than it had before Katrina, and the Risk Reduction System (note that it’s no longer called a “flood protection system”) worked well during Hurricane Isaac in 2012.

That’s the good news. The bad news, Campanella observes, is that the coastal wetlands beyond the system, starved of sediment and freshwater, continue to subside and erode at rapid paces in the face of rising sea levels and intruding sea water.

A Difficult Road Ahead

Solving New Orleans’ geophysical problems is critical for long-term growth. “We have to approach this as a win-win proposition,” says the Nature Conservancy’s Seth Blitch. “Everyone knows if we do nothing, it’s a lose-lose for everyone.”

In the near term obstacles include the growing disparities of race and class, the fall in oil prices, and the strengthening dollar,which could slow the recent surge in capital investment into Louisiana’s industrial economy that has come on the heels of the surge in natural gas production.

While challenges abound, progress over the past 10 years is undeniable, and few would have predicted the city would have come this far so soon in addressing its long-term challenges. “None of this would have happened without Katrina,” says Loyola theologian and philosopher Michael Cowan. “It changed forever what had been an inertial environment. After Katrina, it was like operating in zero gravity. Katrina broke the pattern.”

This piece first appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo montage by Richard Campanella.