Southern California faces a serious middle income housing affordability crisis. I refer to middle income housing, because this nation has become so successful in democratizing property ownership that the overwhelming majority of middle income households own their own homes in most of the country.

Recently I had the privilege of participating in a forum on this subject sponsored by the Urban Land Institute, Los Angeles Housing Chapter in Century City. The forum also included a presentation from USC Professor Dowell Myers and was chaired by Ehud Mouchly, who chairs the Housing Chapter. This article is adapted from my presentation.

I am a native Angeleno, having been born near Temple and Alvarado, less than two miles from City Hall. I was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (LACTC) by Mayor Tom Bradley, where I played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Los Angeles rail system. LACTC and SCRTD were the two predecessors to the current Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA).

In addition, for 11 years, Hugh Pavletich of Christchurch, New Zealand and I have published the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey. The latest edition was released in January and included median multiple data for 86 major metropolitan areas and nearly 300 smaller metropolitan areas in nine nations. Finally, I publish the most comprehensive annual review of world urbanization, providing population, land area and density for world urban areas with over 500,000 population (See World’s 1,000 Largest Cities: World Urban Areas 2015 Edition).

All of this makes housing in Southern California and urban development particularly interesting to me.

The Imperative: A Rising Standard of Living and Less Poverty

The title of the forum was "The Changing Demographics of Southern California and Their Impact on Housing," however I think that the reverse is more significant — the impact housing is likely to have on Southern California.

My perspective is neither ideological nor tied to any political party. It is a fundamentally pragmatic view that domestic policy should principally seek to better people’s lives, by facilitating a rising standard of living and reducing poverty. These objectives were also referenced in the G20 nations communiqué in Brisbane and adopted a announcing a dedication to improving standards of living and eradicating poverty.

The issue is particularly ripe in California, where public policies relating to housing are having virtually the opposite effect. Housing costs have already increased poverty and reduced the discretionary income of middle-income households.

This is not an issue of suburbs versus the urban core. I could not be more pleased by the long overdue resurgence of downtown areas as residential locations, something made possible by the huge crime reductions that began with Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s policies in New York City and similar efforts in cities like Los Angeles. It is important to recognize that a vibrant core no more needs dying suburbs then vibrant suburbs need a dying core. Both urban cores and suburbs can prosper, creating a stronger urban area.

The Housing Crisis

Southern California’s biggest crisis relates to housing. Housing is important to the standard of living and alleviating poverty. It is the largest element of household budgets. When housing more expensive, it leaves households with less discretionary income to purchase other goods and services. This will, other things being equal, reduce economic output from levels that would be otherwise attained.

This has been developing for more than four decades as house price to income ratios (such as the median multiple, the median house price divided by the median household income) have doubled and tripled above historical levels and well above those of other metropolitan areas. Attention is often focused on lower income affordable housing, a problem virtually everywhere, but most parts of the country do not suffer so severe a middle-income housing affordability problem. Low-income housing affordability is important and one of the best ways to minimize it is to ensure that there is middle-income housing affordability.

A bit of historical perspective is appropriate. For centuries nations had little or no property-owning middle class. Huge progress has been made in the last century and particularly since World War II. Following the war, housing development innovation, combined with transportation advances, led to the development of owned middle income housing in the suburbs. It started with Levittown on Long Island and spread across the nation. The most fabled Southern California example is Lakewood (see D. J. Waldie’s Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir on this). The result was a massive increase in home ownership, rising from percentages from the low 40s to 65% in the final decades of the 20th century.

Similar progress was made in other countries, especially in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, where middle-income households purchased homes with sufficient space. In each of these nations, the median multiples were around or below 3.0 as late as 1995.

All of this represented progress toward what the late and renown British urbanist Peter Hall called the "ideal of a property owning democracy" (See: The Costs of Smart Growth Revisited: A 40 Year Perspective).

Sadly, affordability has diminished greatly in many metropolitan areas around the world. House prices relative to incomes have doubled or tripled in virtually all of the metropolitan areas of Australia and New Zealand, some metropolitan areas in Canada as well as in some key metropolitan areas in the United States, with the worst in California. In each of these places, this house price escalation occurred after implementation of urban containment policies (also called smart growth or growth management), which seriously reduce the amount of land that can be used for new housing.

The Roots of Urban Containment Policy

Urban containment has its roots in the British 1947 Town and Country Planning Act. This act created green belts around British cities and is a proximate cause of the present housing shortage and crisis. The general philosophy of the 1947 Act is evident throughout urban planning in the United States and has been implemented in Oregon, part of Washington and California. Urban containment policy was also enacted in Florida. There, house prices had escalated at rates — if not the price levels — to near that of California during the housing bubble. However, legislators took the opportunity to repeal Florida’s urban containment policies when housing prices dropped to historical median multiple levels.

A recent California Legislative Analyst’s report indicated that much of the problem is California’s strict land-use laws and regulations (See: How the California Dream Became a Nightmare). A dense mesh of "urban containment" and "smart growth" regulations have severely limited the land available for new housing, especially on the periphery, where cities grow organically. This destroys the competitive market for land, driving up its cost. This makes house prices escalate in relation to incomes.

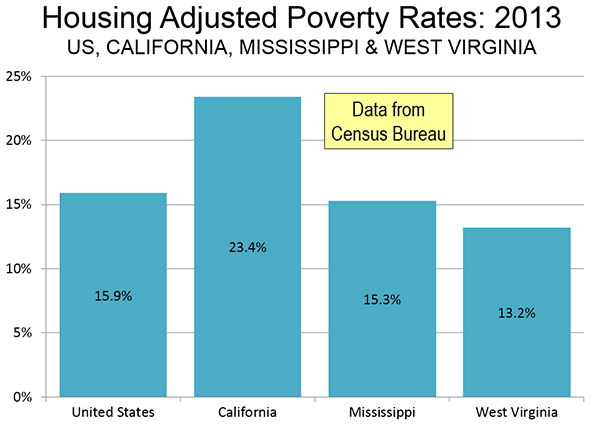

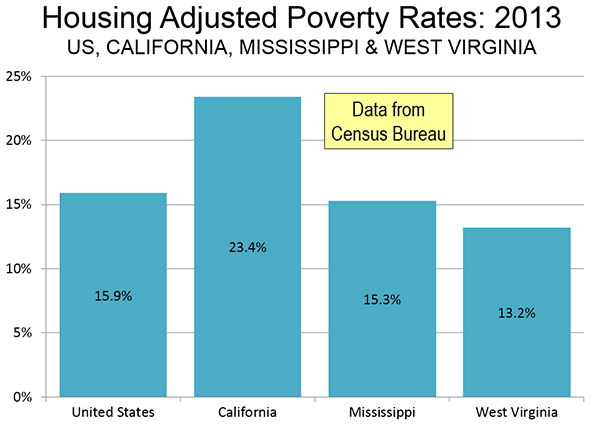

California: 50% More Poverty Than Mississippi

Today, California house prices are far higher than in the rest of the nation. This is taking a toll on the standard of living and increasing poverty. The Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measure, which adjusts for housing costs shows California’s poverty rate to be the highest in the nation. It should be of concern that California’s poverty rate is 50% above that of perennial poverty leader Mississippi (Figure).

Because so much poverty is concentrated among minority ethnic populations, California’s urban containment policy is particularly disadvantaging Hispanics and African-Americans. The Thomas Rivera Institute at USC published a detailed examination of California’s land-use regulations and found that "Far from helping, they are making it particularly difficult for Latino and African American households to own a home."

The Need for Reform

The bad news is that things are likely to get much worse. Under the Sustainable Communities Strategies required under Senate Bill 375 (2008), it is likely to become nearly impossible to build traditional suburban single-family housing in California’s metropolitan areas (See: California Declares War on Suburbia). Already, median multiples in San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles and San Diego are approaching the highs reached at the peak of the housing bubble. House prices are likely to continue rising relative to incomes, other things being equal.

Allowing Supply to Meet Demand

It is often asserted that diminishing land supply in California reflects not so much regulation, but physical limits. The state is sometimes seen as ‘built out’. Yet, in fact, there is plenty of land available for development. Despite its reputation for urban sprawl, the Los Angeles urban area is the most densely populated in the United States. It covers a bit more than one half the land area of the New York urban area. Like any urban area, the greenfield land that is available for development is on the periphery, which includes areas like the northern Antelope Valley, the Victor Valley, and Southwestern California (Temecula to Hemet) and in some closer areas. Each of these areas is closer to the urban core than some parts of the New York commuter shed.

These areas could easily accommodate the additional population expected in the area by 2060, including the single family housing generally preferred among middle-income households. Households are not likely to raise children on high rise balconies.

Even so, the urban footprint would continue to be much smaller than that of New York. If sufficient land were opened to development, the city would expand geographically, but people would also have better access to middle class standards of living, and there would likely be a lot less poverty. The obvious choice would be to let the city expand, while improving real incomes and reducing poverty.

The California Dream is Now in Denver?

During the discussion period after my talk, perhaps the most prescient comment was made by an unidentified audience member said that the California dream is now in Denver. California’s unjustifiably and artificially high housing prices are the cause. Between 1993 and 2010, there was net out-migration from California to 42 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Immigration to Los Angeles and Orange from abroad has also declined, as immigrants too look for more affordable alternatives. People seeking sun, glamour or a good time will continue to flourish in southern California, but it seems likely that more families, and middle class households, will continue to ebb out, seeking somewhere else the dream that was once so closely identified with Southern California.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris. Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism and is a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University.

Photo: Central Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley (by author)