Over the last fifty or sixty years most towns have been dedicated to accommodated cars in order to cultivate business and permit people to live better more convenient lives. For new developments out in a former corn field this was effortless since everything was custom built with the automobile in mind. But older towns that had been built prior to mass motoring were at a distinct disadvantage.

In order to keep up with changing times older neighborhoods, particularly older Main Street business districts, did whatever possible to retrofit themselves. The roads were widened, sidewalks were narrowed, street trees were removed, obsolete buildings were torn down to make way for parking lots, new zoning regulations and building codes were introduced to ease traffic and ensure abundant free parking. Unfortunately for many historic towns there simply was no contest. New strip malls and office parks could provide endless free parking and massively wide roads. If you add in the competition from big box national chains and the politics of race and class driving people across municipal borders for lower taxes and segregated school districts… Main Street never had a chance. The irony is that the more towns tried to accommodate cars the less pleasant they became.

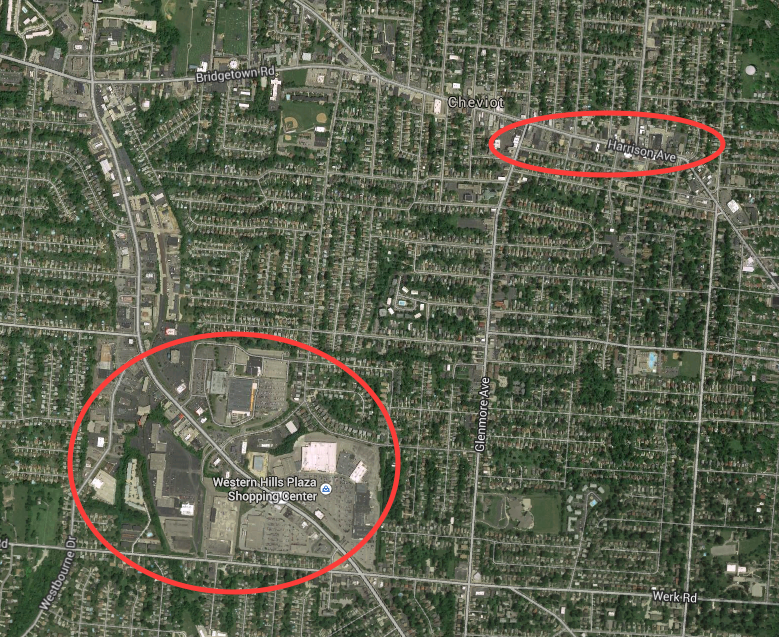

This is a Google Earth image of the area around Cheviot, Ohio. The people of Cheviot self-identify with the fictional 1950’s TV town of Mayberry made famous by The Andy Griffith Show. It really is a lovely place, but it effectively has no business district anymore thanks to the Western Hills Plaza Shopping Center half a mile away which straddles Green Township and the Westwood district of suburban Cincinnati. Harrison Avenue, Cheviot’s century old Main Street, is circled at top right. Western Hills Plaza is circled at bottom left. The Home Depot, Target, Kroger, and Dillard’s make it impossible for mom and pop shops on Harrison Avenue in Cheviot to sustain themselves. Half the shops are empty and the others limp along. It’s a shame, because Cheviot is a charming town full of great old commercial buildings and solid housing stock. It’s a good town full of good people. The German Catholics who settled and built this part of Ohio have managed to hold on to a fair-to-middling set of arrangements through the worst years of decline, but the town is a shadow of its former self. It has excellent bones, but the flesh is sagging through no fault of its own.

However, Cheviot has one thing that Western Hills Plaza doesn’t – a walkable, bikable, fine-grained pleasant neighborhood. That may not sound like much, but it’s more than nearly anyplace built after 1950 anywhere in North America can boast. Cheviot is an actual town, not just mindless suburban sprawl. That’s a rare commodity these days and a lot of people are hungry for it. Just about every home in Cheviot is within a five or ten minute walk of the old business district, local public schools, library, churches, and parks. It has become unusual in America for people to live in this kind of environment and it’s coming back in fashion with increasing demand and limited supply. There’s an opportunity here for people with the right attitude.

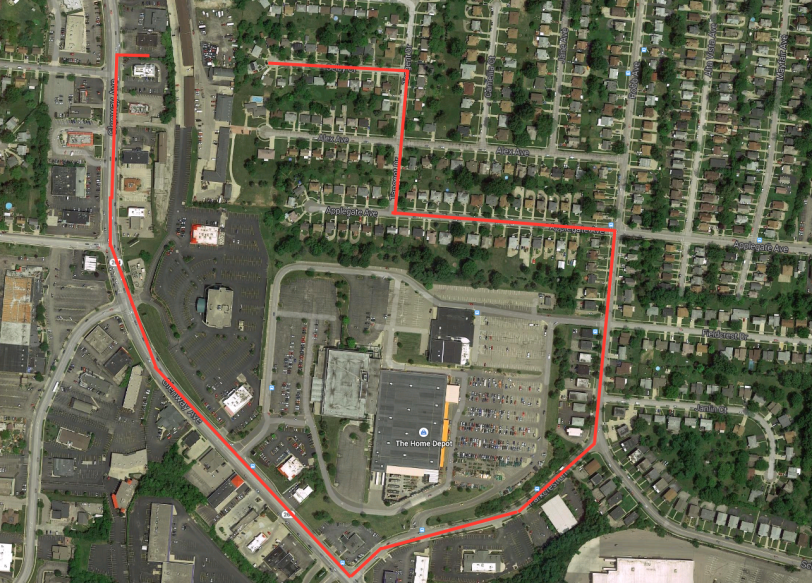

In contrast let’s say that you lived here on this cul-de-sac in Green Township and you wanted to go to one of the fast food places directly behind your back fence. This is the route you’d need to take.

If you’re used to driving everywhere everyday you might not think twice about hopping in the car. In fact, you might not even realize that the Burger King and KFC are so close. But if you were somehow forced to walk one day you might be surprised at how hard it would be given all the walls, fences, and drainage ditches that stand between you and your fast food. And the walk would be a miserable and potentially dangerous experience. The highway and its cavalcade of concrete and plastic bunkers is so wretched when you aren’t in a car that developers and city planners go out of their way to keep homes as isolated and buffered as possible. This radical separation of uses makes perfect sense in a car-oriented environment. Who wants to look out at a highway strip mall from the back yard? But it’s Hell on foot. And don’t even think of riding a bike. You’ll either get hit by a speeding car or attract the attention of the local police who will immediately identify you as a deviant. Being a pedestrian or cyclist in this environment constitutes “probable cause”. You must be unsavory if you lower yourself to such desperation here. Sitting at a bus stop in this setting is no joy either.

So here’s the challenge of the next few decades. The aging sprawl in Green Township and similar nearby post war suburbs like White Oak, Sharonville, and Deer Park on the edge of Cincinnati aren’t aging well. Their roads and sewer systems are right at the point where they need complete overhauls and there’s no money for any of it. Don’t expect Columbus or Washington to send big checks because they’re broke too. The housing stock in these places is neither charming in a Norman Rockwell sort of way, nor sufficiently Mad Men modern. Their roofs, windows, kitchens, baths and furnaces all need replacing right about now and there isn’t a lick of insulation in most of them. Fifty years ago these suburbs were white middle class havens with their backs to inner city decay and race riots.

Now newer more prosperous suburbs Like Mason and Beavercreek farther out attract wealthier residents looking for larger homes with all the latest bells and whistles along with premium public schools and lower taxes. Green Township has less than half the average family income of Mason. Homes in Green Township and other similar areas sell for $75,000 although many homes can be found for considerably less. Mason homes sell for north of $250,000 with many at much higher price points. Meanwhile downtown Cincinnati and Over-the-Rhine are rapidly gentrifying as people who prefer an urban environment reinvigorate long abandoned neighborhoods. The poor are being displaced in the process and they’re going to have to live somewhere. Given the trajectory of these shifts it isn’t looking good for the so-so suburbs in the middle distance. We can expect more “Fergusons” on the horizon although the particulars are unknowable at this time. This economically induced migration won’t be good for the poor either. They just spent the last few generations sucking up the desiccated crumbs of 19th Century industrialism and now they’re being shunted off to the stale left overs of 20th Century sprawl just in time for it to die.

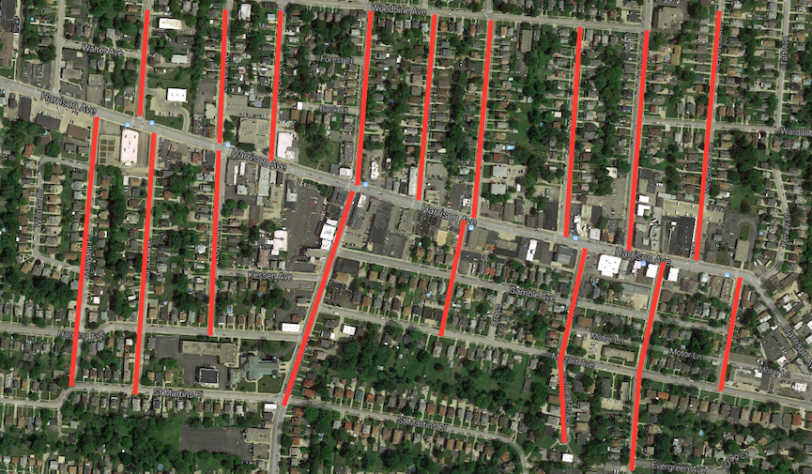

But there’s hope for some of these places. Pressed up against both Cheviot and Green Township is Westwood, a former streetcar suburb that also uses Harrison Avenue (the old streetcar route) as its long-lost Main Street. Westwood was once an independent town, but was annexed by Cincinnati a hundred years ago. It fell out of favor beginning in the 1950’s when the streetcar was ripped up and shiny new subdivisions and shopping centers were built-in places like Green Township. Moving children out of Cincinnati public schools to another jurisdiction a mile away was one of the primary motivations as racial tensions in the city grew. Taxes were also lower in the new suburbs. (Is any of this ringing a bell?) Cincinnati has recently figured out that it can’t compete with Mason or Beavercreek for that particular share of the upscale suburban real estate market, but it’s looking at the success of Over-the-Rhine and wondering what the family friendly conservative Republican Catholic version of revitalization might look like in Westwood. In other words, what can parts of Cincinnati provide in the way of a value-added “product” or “experience” in their century old neighborhoods of single family homes that Mason can’t. There’s a chance that Westwood’s competitive advantage might just be walkability and historic charm. The city adopted a form based code for this part of Westwood and has been investing money in the schools and parks with plans to create a town square in what is now an awkward triangular intersection next to the Carnegie library. There are also existing businesses and subtle interdependent institutions that simply don’t exist out in new suburban locations. If you want your cello or violin repaired you’re not going to find that sort of thing at the mall between the food court and the Sunglass Hut. A more pedestrian oriented Westwood with unique family oriented destinations and activities could be an engine that pulls the area in a better direction. Sooner or later all those Hipsters downtown are going to start getting married and having kids and their going to want a house with a patch of garden. There could be an advantage to having that life three miles from downtown instead of twenty-two miles out in Mason. On the other hand, Westwood could simply languish and be dragged down by the failing sprawl that surrounds it. It could go either way. Time will tell.

John Sanphillippo lives in San Francisco and blogs about urbanism, adaptation, and resilience at granolashotgun.com. He’s a member of the Congress for New Urbanism, films videos for faircompanies.com, and is a regular contributor to Strongtowns.org. He earns his living by buying, renovating, and renting undervalued properties in places that have good long term prospects. He is a graduate of Rutgers University.