Perhaps nothing is as critical to America’s future as the trajectory of the middle class and improving the prospects for upward mobility. With middle-class incomes stagnant or falling, we need to find a way to generate jobs for Americans who, though eager to work and willing to be trained, lack the credentials required to enter many of the most lucrative professions.

Mid-skilled jobs in areas such as manufacturing, construction and office administration — a category that pays between $14 and $21 an hour — can provide a decent standard of living, particularly if one has a spouse who also works, and even more so if a family lives in a relatively low-cost area. But mid-skilled employment is in secular decline, falling from 25% of the workforce in 1985 to barely 15% today. This is one reason why middle- and working-class incomes remain stagnant, well below pre-recession levels.

Over the past three years, high-wage professions have accounted for 29% of new jobs created, while the lowest-paid jobs (under $13 an hour) have grown to encompass roughly half of all new jobs. Net worth-wise, as a recent Pew study notes, the wealthy — the top 7% — are thriving due to the rebound of the stock and bond markets; the bottom 93%, whose wealth is more tied up in their homes, is still feeling the hangover from the cratering of housing prices in the recession.

No surprise then that about a third of all Americans now consider themselves lower class, according to another Pew study, up from a quarter before the recession.

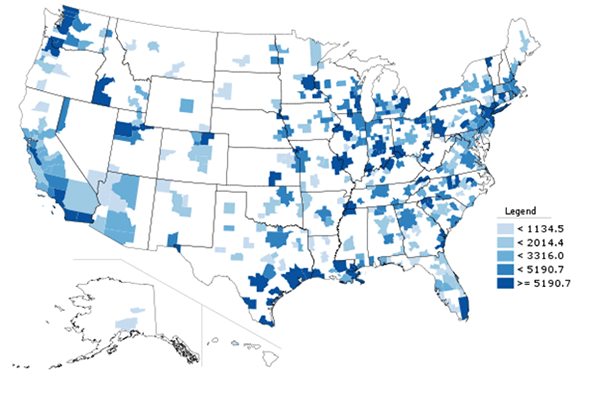

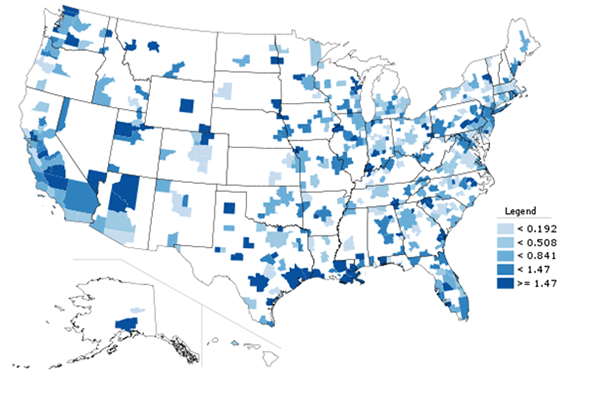

But middle-income employment has not vanished everywhere. An analysis of the distribution of new jobs since 2010 by Economic Modeling Specialists, Inc. found a wide disparity among the states. Between 34% and 45% of all new jobs have been mid-wage in Wyoming, Iowa, North Dakota, Michigan and Arizona. The worst performers: Mississippi where only 10% of new jobs have been middle-income, followed by New York, New Hampshire, New Jersey and Virginia, all with 14% or less. (Note: I use the terms “mid-skill” and “middle-income” interchangeably; recent research suggests pay is a reasonable proxy for skill.)

Generally speaking mid-skilled employment is expanding the most in states with strong overall job growth, and less in high-cost, high-tax states, with the notable exception of Mississippi. The EMSI data also suggest that states with expanding heavy industries such as oil and manufacturing generate more positions for mid-level workers such as machinists, truck drivers, welders and oil roustabouts. At the same time, the states with a bifurcated combination of low-wage industries, like hospitality or retail, and high-paid professions, like software engineers or investment bankers, tend to have fewer opportunities for middle-income workers.

This pattern becomes clearer if we look at metropolitan areas, the level at which most economic activity takes place. Mark Schill at the Praxis Strategy Group crunched the data for us on employment trends over the five years since the recession in the 51 metropolitan statistical areas with over 1 million people. It’s not a pretty picture. Three years since employment hit bottom, the U.S. still has 2 million fewer mid-income jobs than at the onset of the financial crisis in 2007; half of that deficit is in the largest metro areas.

But the pain is not evenly distributed. There are eight metro areas that boast more mid-level jobs today than in 2007. The list is dominated by Texas cities, led by Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, which has added 17,000 mid-skill jobs — an increase of 7.6% – among the 95,000 new jobs generated in the region. The largest numeric increase is in Houston-Sugarland-Baytown, which has 60,810 more mid-skilled jobs, up 7.4%. The Houston metro area also has easily led the nation in overall job growth since 2007, adding a net 280,000 positions.

Texas metro areas also come in third and fourth: in San Antonio-New Braunfels, middle-income employment rose 3.4%; in Dallas-Ft. Worth-Arlington , 3.1%. Nearby Oklahoma City comes in fifth with 2.1% growth in middle-income employment, sharing the merits of relatively low costs and a strong energy economy.

The working class and the endangered middle class may be favored topics of discussion in the deepest blue regions, but for the most part these metro areas have failed to bolster their middle-skilled labor forces. Los Angeles-Long Beach leads the league with the biggest net loss of mid-skilled jobs since 2007, down by 112,300, or 6.1%. Chicago had the second-largest numerical decline, some 102,100, or 7.6%, followed by New York, which lost 82,350 such jobs, 3.4% of its total in 2007. In contrast, notes economist Tyler Cowen, Texas has not only created the most middle-income jobs, but a remarkableone-third of all net high-wage jobs created over the past decade.

The loss of manufacturing jobs is clearly part of the problem here; despite the recent resurgence in the industrial sector, the U.S. still has 740,000 fewer middle-skill manufacturing jobs than in 2007. Chicago and Los Angeles remain the nation’s largest industrial regions, but they are also among the most rapidly de-industrializing areas in the country. New York City, once among the world’s leading industrial centers, with roughly a million manufacturing workers in 1950, is down to around 75,000. In contrast, industrial employment has been expanding in the Houston, Seattle and Oklahoma City metro areas, and recently even Detroit.

In contrast, New York, Chicago and L.A. have seen job gains in such low-wage areas as hospitality and retail, as well as a smaller surge in high-end employment — notably in information and business services. But the welcome growth in these positions is not enough to make up for the big hole in middle-class employment. Since the recession, for example, New York has lost manufacturing and construction jobs at a double-digit rate while hospitality employment grew 18% and retail 10%. Los Angeles and Chicago showed similar patterns, but actually did worse in higher-wage sectors, like professional business services.

Another major area of lost middle-class jobs has been construction. The U.S. is still down 1.2 million middle-skill construction jobs since 2007 and 125,000 in real estate. These losses have inflicted the most pain in the boom towns that grew fastest in the early 2000s. The biggest loser of mid-skill jobs in percentage terms is Las Vegas-Paradise, Nev., which has suffered a staggering 16.1% loss in such jobs since 2007. It’s followed by Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, Calif. (-10.6%); Sacramento-Arden-Arcade-Roseville, Calif., (-10.4%); Tampa- St. Petersburg- Clearwater, Fla. (-9.7%); and Phoenix-Mesa- Scottsdale, Ariz. (-9.3%).

Whether in the biggest cities, or Sun Belt boom towns, the issue of increasing middle-income employment should be as much of a priority for policymakers as attracting glamorous high-wage jobs or helping the poor. America’s identity has been built around the idea that hard work, particularly with some study for a particular skill, should be rewarded with decent pay. Boosting employment in mid-skill professions, from construction and manufacturing to logistics and energy, is critical to achieving this goal.

If we fail to stem the erosion of middle-income jobs, we will be faced with a continued descent into a Latin American style society divided largely between an affluent elite and multitudes of the poor, with a thin layer in the middle. This promises miserable consequences for most Americans and the future of our democracy.

Note: An early version of this table listed incorrect figures in the 2013 total jobs column.

| Middle-skill Employment in U.S. Metropolitan Areas | ||||||

| Metropolitan Statistical Area Name | 2013 Middle Skill Jobs | 2007-2013 Change | % Change | % Change Rank | 2013 Location Quotient | 2013 LQ Rank |

| Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, TX | 248,988 | 17,485 | 7.6% | 1 | 0.93 | 41 |

| Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX | 878,038 | 60,810 | 7.4% | 2 | 1.00 | 17 |

| San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX | 310,920 | 10,316 | 3.4% | 3 | 1.07 | 3 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | 959,326 | 29,178 | 3.1% | 4 | 0.98 | 23 |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 198,944 | 4,113 | 2.1% | 5 | 1.05 | 8 |

| New Orleans-Metairie-Kenner, LA | 177,207 | 2,676 | 1.5% | 6 | 1.05 | 8 |

| Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN | 263,022 | 2,309 | 0.9% | 7 | 1.02 | 12 |

| Salt Lake City, UT | 221,892 | 476 | 0.2% | 8 | 1.07 | 3 |

| Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, CO | 390,661 | (2,824) | -0.7% | 9 | 0.96 | 31 |

| Indianapolis-Carmel, IN | 274,996 | (3,143) | -1.1% | 10 | 0.98 | 23 |

| Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH | 700,371 | (9,683) | -1.4% | 11 | 0.90 | 46 |

| San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA | 233,796 | (5,012) | -2.1% | 12 | 0.78 | 51 |

| Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN | 199,292 | (4,669) | -2.3% | 13 | 1.04 | 10 |

| Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill, NC-SC | 267,840 | (6,888) | -2.5% | 14 | 0.98 | 23 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | 358,823 | (9,301) | -2.5% | 15 | 1.03 | 11 |

| Rochester, NY | 147,269 | (4,325) | -2.9% | 16 | 0.97 | 28 |

| Raleigh-Cary, NC | 153,838 | (4,854) | -3.1% | 17 | 0.93 | 41 |

| Baltimore-Towson, MD | 391,208 | (12,532) | -3.1% | 18 | 0.95 | 34 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | 764,805 | (25,078) | -3.2% | 19 | 0.80 | 50 |

| San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA | 492,724 | (16,382) | -3.2% | 20 | 1.09 | 2 |

| New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA | 2,336,777 | (82,350) | -3.4% | 21 | 0.88 | 48 |

| Columbus, OH | 272,821 | (9,829) | -3.5% | 22 | 0.95 | 34 |

| Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY | 159,658 | (5,770) | -3.5% | 23 | 0.99 | 20 |

| Richmond, VA | 193,104 | (7,081) | -3.5% | 24 | 1.00 | 17 |

| San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA | 583,934 | (21,618) | -3.6% | 25 | 0.87 | 49 |

| Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | 543,988 | (21,651) | -3.8% | 26 | 0.97 | 28 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | 507,261 | (20,643) | -3.9% | 27 | 0.91 | 45 |

| Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA | 337,705 | (19,386) | -5.4% | 28 | 1.02 | 12 |

| Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT | 179,653 | (10,578) | -5.6% | 29 | 0.95 | 34 |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | 789,395 | (49,105) | -5.9% | 30 | 0.95 | 34 |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA | 692,336 | (44,530) | -6.0% | 31 | 0.95 | 34 |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA | 1,731,419 | (112,332) | -6.1% | 32 | 0.96 | 31 |

| St. Louis, MO-IL | 393,900 | (27,502) | -6.5% | 33 | 0.98 | 23 |

| Kansas City, MO-KS | 302,025 | (21,222) | -6.6% | 34 | 0.98 | 23 |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR | 192,693 | (14,600) | -7.0% | 35 | 1.02 | 12 |

| Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI | 517,098 | (39,268) | -7.1% | 36 | 0.93 | 41 |

| Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL | 304,724 | (23,533) | -7.2% | 37 | 0.95 | 34 |

| Cincinnati-Middletown, OH-KY-IN | 302,932 | (24,111) | -7.4% | 38 | 1.00 | 17 |

| Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL-IN-WI | 1,249,263 | (102,122) | -7.6% | 39 | 0.94 | 40 |

| Jacksonville, FL | 200,324 | (16,482) | -7.6% | 40 | 1.06 | 6 |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC | 298,352 | (25,147) | -7.8% | 41 | 1.19 | 1 |

| Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL | 706,788 | (60,373) | -7.9% | 42 | 0.97 | 28 |

| Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI | 237,871 | (20,489) | -7.9% | 43 | 0.96 | 31 |

| Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH | 304,167 | (27,158) | -8.2% | 44 | 0.99 | 20 |

| Birmingham-Hoover, AL | 162,440 | (15,437) | -8.7% | 45 | 1.07 | 3 |

| Providence-New Bedford-Fall River, RI-MA | 206,473 | (20,670) | -9.1% | 46 | 0.99 | 20 |

| Phoenix-Mesa-Glendale, AZ | 578,767 | (59,101) | -9.3% | 47 | 1.02 | 12 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL | 365,043 | (39,371) | -9.7% | 48 | 1.02 | 12 |

| Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville, CA | 259,792 | (30,200) | -10.4% | 49 | 0.92 | 44 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA | 431,892 | (51,373) | -10.6% | 50 | 1.06 | 6 |

| Las Vegas-Paradise, NV | 234,340 | (44,849) | -16.1% | 51 | 0.89 | 47 |

| Total | 23,210,895 | (1,045,210) | -4.3% | |||

| Source: EMSI Class of Worker – QCEW Employees + Non-QCEW Employees + Self-Employed Analysis by Mark Schill, Praxis Strategy Group |

||||||

This story originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.