Our tepid economic recovery has been profoundly undemocratic in nature. Between the “too big to fail” banks and Ben Bernanke’s policy of dropping free money from helicopters on the investor class, there have been two recoveries, one for the rich, and another less rewarding one for the middle class.

Viewed in this light, the recent run-up in home prices, the biggest in seven years, offers some relief from this dreary picture. Home equity accounts for almost two-thirds of a “typical” family’s wealth (those in the middle fifth of U.S. wealth distribution); there is no other investment by which middle-class families can so easily grow their nest eggs.

But the housing recovery’s benefit extend beyond owners. The housing industry drives a significant portion of the nation’s economy, accounting for millions of jobs. According to the National Association of Home Builders, the average single-family detached house under construction results in an additional three jobs for one year. This includes the employees working on the house, and those employed in producing products to build the house.

Overall, residential construction and upkeep generates between 15% and 18% of GDP. If the economy is to expand in a sustainable way that helps a broad section of Americans, suggests Roger Altman, a Clinton administration deputy Treasury secretary, “a housing boom will be the biggest driver.”

Perhaps even more important, the growth of housing sales also revives something many have written off as obsolete: “the American dream” of owning a home. Since the great recession, some economists have argued that the future of America will be a “rentership” society.

Others such as Richard Florida have argued forcibly that home ownership is “over-rated,” maintaining that America’s fixation on it has fostered “countless forms of over-consumption that have a horribly distorting affect on the economy.” Workers, he argues, are better off as renters since this allows them to change jobs more nimbly. If anything, he suggests, the government would be better off encouraging “renting, not buying.”

Greens have also embraced this downscaled future, with people living cheek to jowl in some urbanized form of ecological harmony. They envision a new generation that will reject materialism, suburbs, single-family homes and other expressions of acquisition. In other words, forget ambition and save the whales. One writer at Grist argues, the fact the millennial generation can’t afford homes is a good thing, since it will lead to “a rejection of the mindset that got us into this mess.” Welcome back to the green Age of Aquarius: “we’re looking for ways to avoid that ladder altogether — maybe by climbing a tree instead.”

Perhaps this is true for some, but overall the desire to own a home is far from dead. A 2012 study by the Woodrow Wilson Center found that over 80% of Americans associated homeownership with the American dream. A 2012 study by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard, found “little evidence to suggest that individuals‘ preferences for owning versus renting a home have been fundamentally altered by their exposure to house price declines and loan delinquency rates, or by knowing others in their neighborhood who have defaulted on their mortgages.”

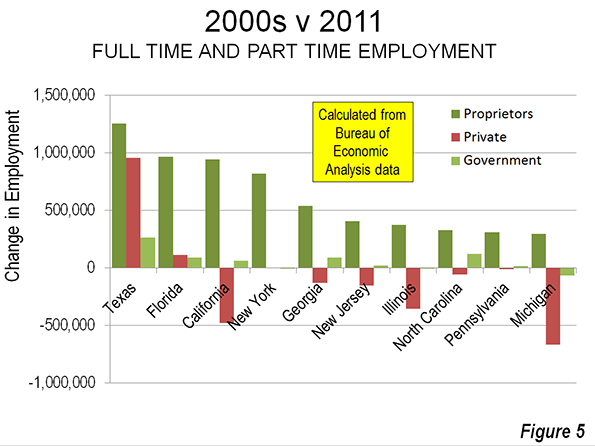

Some predict that changing demographics — and attitudes — will erode such sentiments. Yet homeownership seems to be embraced by two groups who will dominate our future: the emerging millennial generation and immigrants . Between 2000 and 2011, there has been a net increase of 9.3 million in the foreign-born (immigrant) population, largely from Asia and Latin America. These newcomers have accounted for roughly two out of every five new homeowners.

What about millennials? Despite the hopes of the counter-culture enthusiasts, a full 82% of adult millennials surveyed said it was “important” to have an opportunity to own their home. This rose to 90% among married millennials, who generally represent the first cohort of their generation to start settling down. Another survey, by TD Bank, found that 84% of renters aged 18 to 34 intend to purchase a home in the future. Still another, this one from Better Homes and Gardens, found that three in four saw homeownership as “a key indicator of success.”

Over time, these demographics could provide the basis for a new and more widely distributed economic boom hopefully healthier than that which accompanied the last housing boom. For one thing, there are far fewer dubious loans, and lending standards are somewhat stricter. And building activity, although bouncing back, is not as fevered as last time, except perhaps in the somewhat over-hyped multi-family sector. Two-thirds of all housing starts, now at the highest level since June 2008, are single-family homes, a sure sign that the traditional buyer is back.

Yet there are some disturbing aspects of the current housing boom. In much of the country, much of the activity has been fueled by investors; in states such as California they account for roughly one-third of buyers. Large players such as Blackstone and Colony Capital have been particularly active in buying distressed properties in places like Tampa, the Inland Empire and Phoenix, in the process boosting prices.

This has set up what could become a potential conflict between prospective middle-income homeowners and the very deep-pocketed investors who have been the primary beneficiaries of the age of Obama. Although investors have indeed set a “floor” that has prevented a further deterioration of prices, their investment appear to be threatening to push homes out of the reach of middle-income buyers. Some local officials also worry that when the investors tire of their new properties, they may leave them to languish on the market.

This can be seen even in California, which has experienced a weak recovery in jobs and income, but a decisive and escalating increase in housing prices, largely due to the prescence of investors, domestic and foreign, as well as the resurgent flippers. Over the past five years inventory has dwindled from 16 months supply to less than three months. Prices are up over 30% from 2008 in San Francisco and over 17% in the Los Angeles area, driving down affordability.

But, still, the housing recovery is the best news to hit the American middle class in at least half a decade. Some investors seem to be realizing there are limits to rental income and might be persuaded to start selling homes to individuals. Already in Phoenix, a hotbed of investor interest, the percentage of homes sold to investors dropped to about 25% in March from a high of 36% last summer.

If this trend takes hold, investors, rather than undermining the market, could be seen as having played a critical role in maintaining housing during a very hard time. If they start an orderly withdrawal, or start selling their homes to families, the speculators, not always a lovable group, could end up being among the unlikely saviors of the American dream, particularly for the next generation.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com.