For all of human history, family has underpinned the rise, and decline, of nations. This may also prove true for the United States, as demographics, economics and policies divide the nation into what may be seen as child-friendly and increasingly child-free zones.

Where California falls in this division also may tell us much about our state’s future. Indeed, in his semi-triumphalist budget statement, our 74-year-old governor acknowledged California’s rapid aging as one of the more looming threats for our still fiscally challenged state.

Gov. Jerry Brown, unsurprisingly, did not acknowledge or address the many factors driving the aging trend that include his own favored policy prescriptions. Whatever their intent, the usual "progressive" basket of policies have had regressive results: a tougher time for both the poor and middle class, and a set of density-oriented policies that are likely to drive up housing prices, particularly for the single-family houses largely preferred by people with children.

These policies have helped turn California into a state that looks less Sunbelt and more like the long-aging centers of the Northeast and the Midwest. It also mirrors declines in fertility and marriage rates in the most-rapidly aging parts of Europe and east Asia. These regions are shifting toward what Chapman University’s recent report, in cooperation with the Civil Service College of Singapore, characterized as post-familialism. Released this past fall in Singapore, the report will be presented in Orange County this week.

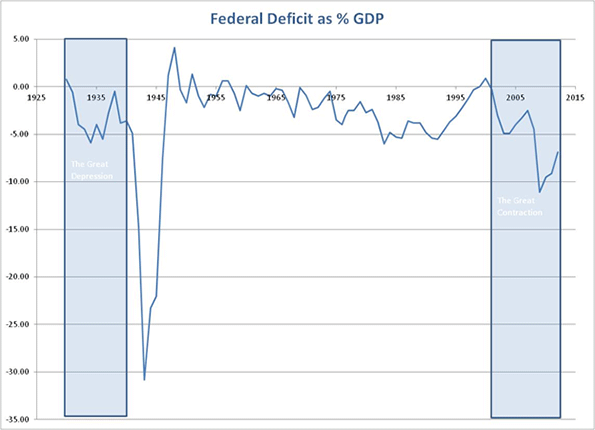

We believe that the rapid decline of marriage and fertility rates in many advanced countries inevitably leads to economic decline, reduced workforces and, likely, an inevitable fiscal disaster. This may be becoming now more true in the United States, a country which once boasted the most vibrant demographics in the high-income world but since the 2007-09 recession has seen a rapid drop in both its marriage rate and fertility rates to well below 2.1 children per female, what is generally referred to as "the replacement rate."

Just as it differs by country, the degree of post-familialism varies among countries, but it also does among states and regions. Some states, notes a recent Packard Foundation study, such as Texas, Utah and North Carolina, have seen double-digit gains in their child populations over the past decade while California’s has dropped by over 3 percent. Some urban regions like Raleigh, Austin, Houston, Charlotte, Dallas-Fort Worth and Atlanta have also seen rises in their number of children, with population between ages 5 and 17 growing by 20 percent or more over the past decade.

Historically, California and its regions stood among these family magnets, but no more. Like the states of the Northeast and upper Midwest, the Golden State is becoming rapidly geriatric, as families opt out, and immigration, the primary source of our growth in younger people, declines in an economy ill-suited to migrants with aspirations for a better life.

Southern California, where immigration has dropped by roughly a third over the past decade, has shared in this decline.

All three major regions of greater Los Angeles – the San Bernardino-Riverside area, Orange and Los Angeles counties – have seen a sharp drop in their percentages of children. Only the Inland Empire remains still relatively youthful overall, with some 26 percent of its population under 15, well above the national average. In contrast, Los Angeles and Orange counties experienced a 15.6 decline in under-15 population, highest among the nation’s metropolitan areas. Meanwhile, the over 60 population grew by 21 percent.

One clear indicator can be seen in our declining school populations. Despite massive expenditures for new construction, over the past decade the Los Angeles Unified School District has seen enrollment drop by 7.5 percent. In that period, the student count fell by over 50,000, the largest numerical drop in the nation.

What is leading to this exodus of families? Sacramento politicians and their media enablers blame insufficient investment in education or simply national aging trends as the root causes. But then, why are other states, including our key competitors, gaining families and children?

Sacramento lawmakers of both parties share some responsibility. The dominant progressives’ regulatory and tax agenda continues to reduce economic prospects for younger Californians, leading many young families to exit the state. In contrast, older Anglos, the bulwark of the now largely irrelevant GOP, are committed to massive property tax breaks because of Proposition 13. Add good weather and the general inertia of age, and it’s not surprising that families might flee as seniors stay.

Other factors work against parents, prospective or otherwise. The knee-jerk progressive response to our demographic problems usually entails more money be sent to the schools.

But they rarely include the student-oriented reform measures such as those enacted in New Orleans (where I am working as a consultant). The poor performance of public education, clear from miserable test results and dropout rates, makes raising children in California either highly problematic or, factoring the cost of private education, extremely expensive.

If you think Proposition 30’s higher sales and income taxes will change anything, think again.

Much of that money will end up, almost inevitably, going toward pensions of teachers and other state workers. The hegemonic teacher unions have as their primary goal protecting the system at all costs and resisting change.

Equally critical, the state’s "enlightened" planning policies also work to discourage families. California’s new climate-change-mandated housing regime – preferring apartments over houses – does not specifically target families, but the case for greater density is often predicated on an ever-declining number of families and an undemonstrated growing preference for density. "Singles and childless couples are the emerging household type of the future," suggests developer and smart growth guru Chris Leinberger.

These post-familial trends have been incorporated into the influential report, "The New California Dream," widely accepted as gospel by many in our state’s development community.

The author, the University of Utah’s Chris Nelson, interpreted early 2000s public opinion surveys to suggest a growing preference for smaller lot sizes and apartments, though the data indicate no change over the past 10 years. Developers assume that as singles, empty-nesters and childless couples become as the state’s primary market, this likely misperceived preference will gain even greater strength

So what would a post-familial future mean for California? You don’t need a crystal ball to figure this one out. Just look at what is happening in other rapidly aging economies, especially Japan, but also much of Europe.

Dense housing, high taxes and lack of space (such as back yards) tend to discourage family formation. Slower population and labor-force growth then slows the economic engine, which, in turn, creates a greater imbalance between workers and pensioners. The result, ultimately, could be a kind of fiscal Armageddon.

Fortunately, none of this is inevitable. States such as Utah, Texas and North Carolina continue to attract families, bringing with them new workers, companies and customers. As their economies grow, they can generate broadly based revenue, unlike California, which is increasingly reliant on housing or stock-price bubbles that benefit the already affluent and older populations.

It is not our karma, Gov. Brown, to submit to a Japanese-like demographic demise. But revitalizing California will require a radical reevaluation of priorities and reconsideration of policy impacts on families.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared in the Orange County Register.

Childhood kids photo by BigStockPhoto.com.