This past weekend the New York Times devoted two big op-eds to the decline of the suburb. In one, new urban theorist Chris Leinberger said that Americans were increasingly abandoning “fringe suburbs” for dense, transit-oriented urban areas. In the other, UC Berkeley professor Louise Mozingo called for the demise of the “suburban office building” and the adoption of policies that will drive jobs away from the fringe and back to the urban core.

Perhaps no theology more grips the nation’s mainstream media — and the planning community — more than the notion of inevitable suburban decline. The Obama administration’s housing secretary, Shaun Donavan, recently claimed, “We’ve reached the limits of suburban development: People are beginning to vote with their feet and come back to the central cities.”

Yet repeating a mantra incessantly does not make it true. Indeed, any analysis of the 2010 U.S. Census would make perfectly clear that rather than heading for density, Americans are voting with their feet in the opposite direction: toward the outer sections of the metropolis and to smaller, less dense cities. During the 2000s, the Census shows, just 8.6% of the population growth in metropolitan areas with more than 1 million people took place in the core cities; the rest took place in the suburbs. That 8.6% represents a decline from the 1990s, when the figure was 15.4%.

Nor are Americans abandoning their basic attraction for single-family dwellings or automobile commuting. Over the past decade, single-family houses grew far more than either multifamily or attached homes, accounting for nearly 80% of all the new households in the 51 largest cities. And — contrary to the image of suburban desolation — detached housing retains a significantly lower vacancy rate than the multi-unit sector, which has also suffered a higher growth in vacancies even the crash.

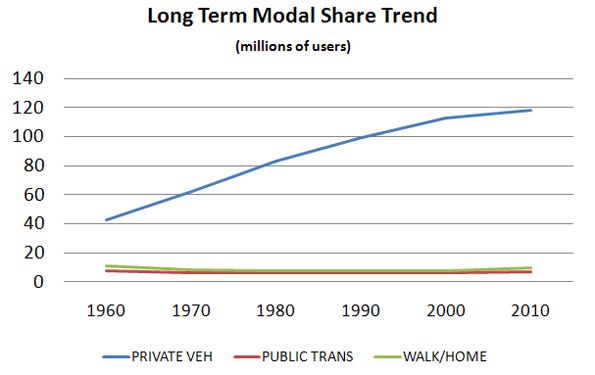

Similarly, notes demographer Wendell Cox, despite a 45% boost in gas prices, the country gained almost 8 million lone auto commuters in the past 10 years. Transit ridership, while up slightly, is still stuck at the 1990 figure of 5%, while the number of home commuters grew roughly six times as quickly.

In the past decade, suburbia extended its reach, even around the greatest, densest and most celebrated cities. New York grew faster than most older cities, with 29% of its growth taking place in five boroughs, but that’s still a lot lower than the 46% of growth they accounted for in the 1990s. In Chicago, the suburban trend was even greater. The outer suburbs and exurbs gained over a half million people while the inner suburbs stagnated and the urban core, the Windy City, lost some 200, 000 people.

Rather than flee to density, the Census showed a population shift from more dense to less dense places. The top ten population gainers among metropolitan areas — growing by 20%, twice the national average, or more — are the low-density Las Vegas, Raleigh, Austin, Charlotte, Riverside–San Bernardino, Orlando, Phoenix, Houston, San Antonio and Atlanta. By contrast, many of the densest metropolitan areas — including San Francisco, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Boston and New York — grew at rates half the national average or less.

It turns out that while urban land owners, planners and pundits love density, people for the most part continue to prefer space, if they can afford it. No amount of spinmeistering can change that basic fact, at least according to trends of past decade.

But what about the future? Some more reasoned new urbanists, like Leinberger, hope that the market will change the dynamic and spur the long-awaited shift into dense, more urban cores.

Density fans point to the very real high foreclosure rates in some peripheral communities such as those that surround Los Angeles or Las Vegas. Yet these areas also have been hard-hit by recession — in large part they consist of aspiring, working class people who bought late in the cycle. Yet, after every recession in the past, often after being written off for dead, areas like Riverside-San Bernardino, Calif., have tended to recover with the economy.

Less friendly to the meme of density’s manifest destiny has been a simultaneous meltdown in the urban condo market. Massive reductions in condo prices of as much as 50% or more have particularly hurt the areas around Miami, Portland, Chicago and Atlanta. There are open holes, empty storefronts, and abandoned projects in downtowns across the country that, if laid flat, would appear as desperate as the foreclosure ravaged fringe areas.

In many other cases, the prices never dropped because the owners gave up selling condos and started renting them, often to a far lower demographic (such as students) than the much anticipated “down-shifting” boomers. Contrary to one of the most oft-cited urban legends by Leinberger and his cohorts, demographics do not necessarily favor density. Most empty-nesters and retirees, notes former Del Webb Vice President of Development Peter Verdoon, prefer not just outer suburbs but increasingly “small towns and rural areas” Dense cities, he notes, are a relatively rare choice for those seeking a new locale for their golden years.

Verdoon’s assertion is borne out by our own analysis of the 2010 Census. Generally speaking, aging boomers tended to move out of dense urban cores, and to a lesser extent, even the suburbs. If they moved anywhere, they were headed further out in metropolis towards the more rural area. Among cities the biggest beneficiaries have been low-density cities in the Southwest and southern locales such as Charlotte, Raleigh and Austin.

What about the other big demographic, the millennials? Like previous generations of urbanists, the current crop mistake a totally understandable interest in cities among post-adolescents. Yet when the research firm Frank Magid asked millennials what made up their “ideal” locale, a strong plurality opted for suburbs — far more than was the case in earlier generations.

Generational analysts Morley Winograd and Mike Hais note that older millennials — those now entering their 30s — are as interested in homeownership as previous generations. This works strongly in favor of suburbs since they tend to be more affordable and, for the most part, offer safer streets, better parks and schools.

In the short run, suburbia’s future, like that of much of real estate market, depends on the economy. But even here trends may be different than the density lobby suggests. As housing prices fall, the much ballyhooed trend toward a “rentership” society may weaken. Already in many markets such as Atlanta, Las Vegas and Minneapolis and Phoenix it is cheaper to own than rent, something that favors lower-density suburban neighborhoods.

Longer term, of course, suburbs, even on the fringe, will change as growth restarts. Cities here and around the world tend to expand outward, and over time the definition of the fringe changes. To be sure, some fringe communities, particularly in highly regulated and economically regressive areas, could indeed disappear; but many others, particularly in the faster growing parts of the country, will reboot themselves.

They will become, as the inner suburbs already have, more diverse with many working at home or taking shorter trips to their place of work They will become less bedrooms of the core city but more self-contained and “village like,” with shopping streets and cultural amenities near what will still be a landscape dominated primarily by single-family houses.

In fact the media reports about the “death” of fringe suburbs seem to be more a matter of wishful thinking than fact. If the new urbanists want to do something useful, they might apply themselves by helping these peripheral places of aspiration evolve successfully. That’s far more constructive than endlessly insisting on — or trying to legislate — their inevitable demise.

This piece first appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

Many US politicians recoil against the state as a real estate developer largely because tenanted housing projects have been such a magnet for social problems. The St. Louis public housing scheme, Pruitt-Igoe, was eventually dynamited (see photo right

Many US politicians recoil against the state as a real estate developer largely because tenanted housing projects have been such a magnet for social problems. The St. Louis public housing scheme, Pruitt-Igoe, was eventually dynamited (see photo right