Dallas was George W. Bush’s first choice for a retirement destination but it gets low approval ratings elsewhere. A recent poll of readers of American Style magazine rated Dallas only 24th out of 25 large American cities as an arts destination. It came in immediately behind those well-known cultural magnets Milwaukee and Las Vegas, and ahead of only Jacksonville FL, even though it dwarfs all three places in terms of population, arts institutions and urban amenities. An apparently typical assessment residing in the blogosphere states flatly “God I hate Dallas. Everything about it. Especially the airport. Which is the only part of Dallas I’ve ever been in.”

There has always been urban rivalry, going back at least to the days of the Greek city-states. When Phoenix overtook Philadelphia in the census rankings some years ago, the local newspapers delighted in printing unflattering pieces about the other and extolling their own virtues.

Increasingly, this rivalry goes beyond traditional boosterism. Cities used to be places where one lived, but they have become metaphors about lifestyle and identity, and the personal has become increasingly highly political.

In the last presidential election, the former mayor of Wasilla, Alaska seemed to argue that small towns were the keepers of the true American flame, which upset quite a few urbanites. But not all cities are created equal. The creative class thesis suggests that, like high school, there is cool and there is un-cool. This gets complicated when the nerds decide the cool places are. Cities that are designated as cool, like Portland, also tend to be among the least ethnically diverse.

In short, we are now quarrelling about which cities are the coolest, based upon the extent to which they serve as extensions of our personalities and manifestations of our identities. This has always existed in terms of local rivalries—New York and New Jersey, Minneapolis and St. Paul—but now it is taking on the characteristics of cultural civil war.

In this scheme of things, Dallas ranks among the totally uncool, which is probably one of the reasons George Bush chose it. But reputation is not necessarily its reality, as visitors to the city can find out for themselves. On a recent Friday afternoon downtown, I saw a line of school buses jostling to drop off and pick up their passengers ranging from young children to strapping adolescents. Every ethnicity seemed to be represented. They were not going to a sports event represented but regular traffic to the Dallas Arts District, a contiguous area amid the high rises that covers 68 acres and contains a broad array of theatres, museums and the city’s Arts Magnet school.

Texas is hardly short of arts destinations: San Antonio ranked high in the American Style poll, as did Austin, which is known for its South by Southwest and Austin City Limits music festivals. Although Dallas does not automatically come to mind when thinking about highbrow culture, its Arts District is not just a vanity project, but is part of a restructuring of the city’s image taking shape for over three decades. The Arts District was anchored by the opening of the Dallas Museum of Art in 1984; this was followed by the Myerson Symphony Center [designed by I.M. Pei], the Crow Collection of Asian Art, the Nasher Sculpture Center, and the renovation of the Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts [Norah Jones is an alumna]. Most recent to open is the AT&T Performing Arts Center, the fourth of the cultural buildings to be designed by a prize-winning architect.

Most metro areas would delight in this kind of enhancement. Yet Harvey Graff, in his book “The Dallas Myth” suggests the city has grown by “brash boosterism”. He argues the ‘Dallas Way’ of getting things done involves an existential denial of the past [especially negative events, notably the Kennedy Assassination] and an equally strong denial of any limits to the future.

Graff believes that the Dallas Way fails its residents. He argues little, if anything, has been done for poorer neighborhoods. There is substance to this of course: all American cities reflect the inequalities of our society

Yet what Dallas is doing is still remarkable. In addition to the Arts District, it is pursuing costly projects such as the DART light rail network, which is connecting formerly neglected neighborhoods [now reviving to create a new Uptown] and reaching out to middle suburbia, where whole plazas are sprouting Asian stores and restaurants. No-one is going to be confusing it with New York any time soon, but it does seem that the Dallas Way also has things to recommend it. House prices have not cratered; the Metroplex is not in the fifth circuit of foreclosure hell like Phoenix or Las Vegas.

Of course, this comes at a literal price, and a figurative one. Reviving some neighborhoods means gentrification. Spending on light rail tends to support young adults rather than children needing kindergartens. Stable house prices in some Dallas neighborhoods can mean modest homes costing more than a half million dollars, the antithesis of affordability.

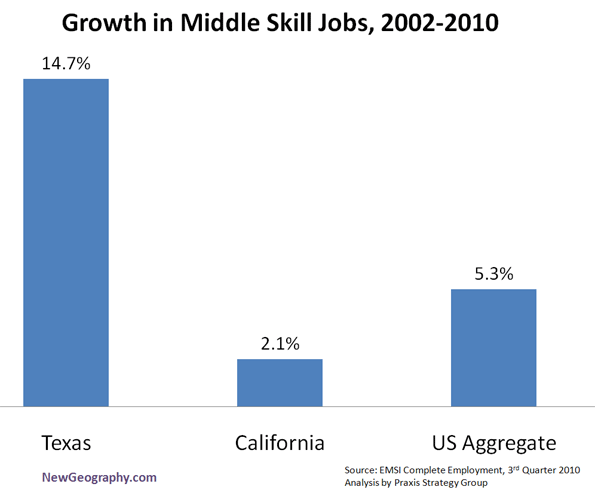

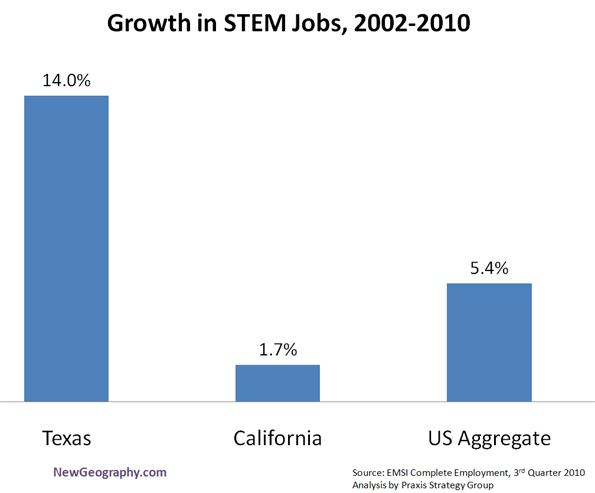

Yet the growth machine worked in the past and helped Dallas become a leading producer of higher end jobs and a high degree of home ownership. In many ways Dallas works better for its diverse residents than many urban aesthetes might suggest.

This leaves unanswered the question of the aspirations of a city like Dallas to be taken seriously by the urban tastemakers. In the current climate, that seems unlikely. Cool is going to beat out the rest—except in the contexts of jobs and incomes, which is the world in which most people operate. Economic growth in Dallas and Houston gets little attention in the chat rooms where the defenders of Portland and its counterparts congregate. But as for me, I’m thinking that for the very first time, George Bush might actually be right.

Andrew Kirby has been associated with the journal *Cities* for nearly thirty years. He is based in Arizona.

Photo by purpletwinkie