Few icons of the American way of life have suffered more in recent years than homeownership. Since the bursting of the housing bubble, there has been a steady drumbeat from the factories of futurist punditry that the notion of owning a home will, and, more importantly, should become out of reach for most Americans.

Before jumping on this bandwagon, perhaps we would do well to understand the role that homeownership and the diffusion of property plays in a democracy. From Madison and Jefferson through Lincoln’s Homestead Act, the most enduring and radical notion of American political economy has been the diffusion of property.

Like small farmers in the 19th century, homeowners–and equally important, aspiring homeowners–now represent the core of our economy without which a strong recovery is likely impossible. Houses remain as a financial bulwark for a large percentage of families, the anchor of communities, and, increasingly, home-based businesses.

The reasons given for abandoning the homeownership ideal are diverse. Conservatives rightfully look to diminish the outsized role of government in promoting homeownership. Some suggest that Americans would be better off putting their money into things like the stock market or boosting consumer purchases.

New-urbanist intellectuals like the University of Utah’s Chris Nelson predict aging demographics will lead masses to abandon their homes for retiree communities and nursing homes. The respected futurist Paul Saffo predicts that as skilled laborers move from Singapore to San Francisco to New York and London, there is little need to “own” a permanent place. In the brave new future, he suggests, we will prefer time-sharing residences as we flit from job to job across the global economy.

Some of the greatest hostility towards homeownership increasingly comes from the progressive left, some of whom are calling for the total elimination of the homeowner mortgage interest deduction. “The Case Against Homeownership,” recently published in Time, encapsulates the current establishment’s conventional wisdom: that homeownership is by nature exclusionist, “sprawl” promoting and responsible for “America’s overuse of energy and oil.”

Yet for all the problems facing the housing market, homeownership–not exclusively single-family houses–is not likely to fade dramatically for the foreseeable future. The most compelling reason has to do with continued public preference for single-family homes, suburbs and the notion of owning a “piece” of the American dream. This is why that four out of every five homes built in America over the past few decades, notes urban historian Witold Rybczynski, have less to do with government policy than “with buyers’ preferences, that is, What People Want.”

What we are going through now is not a sea change but a correction from insane government and business practices. The rise in homeownership from 44% in 1944 to nearly 70% at the height of the bubble reflected a great social democratic achievement. But by the mid-2000s government attempts to expand ownership–eagerly embraced by Wall Street speculators–brought in buyers who would have historically been disqualified.

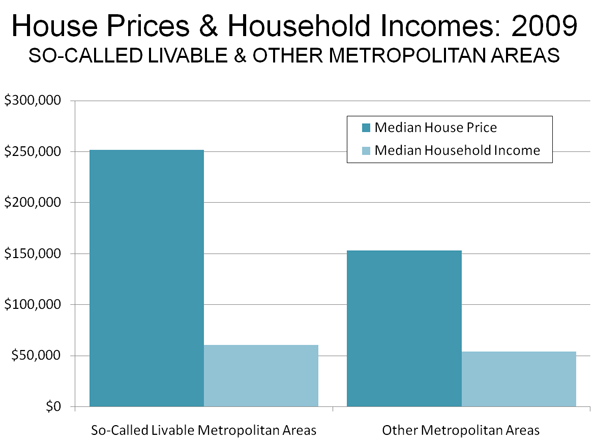

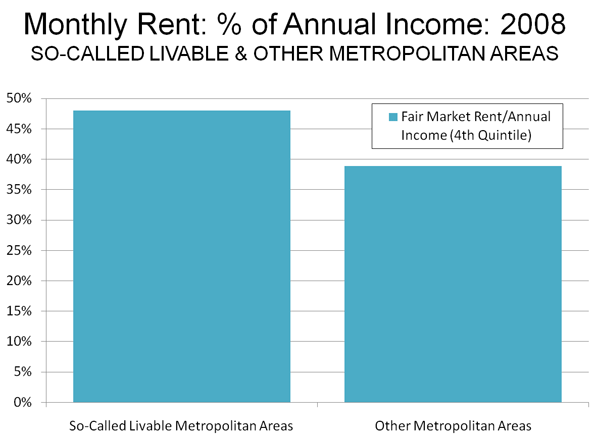

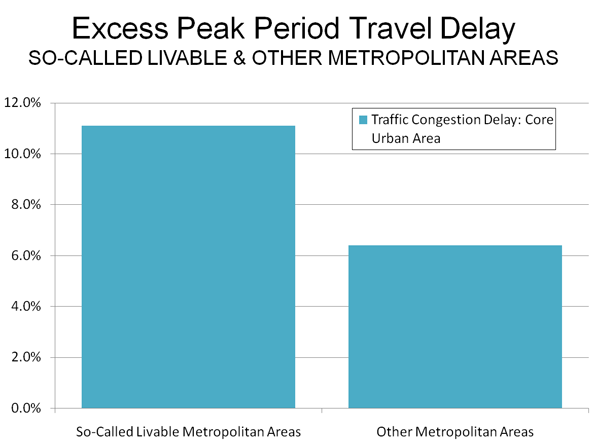

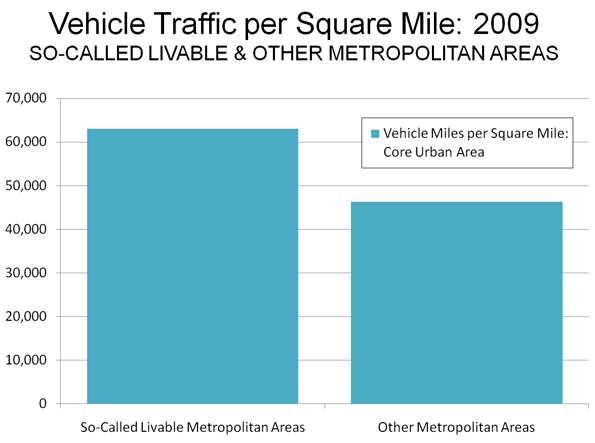

In some markets, prices exploded as people moved up too quickly into ever more expensive housing. Housing inflation was further exacerbated by “smart growth” policies, which limited new home construction in suburban areas and instead promoted dense, “transit oriented” housing with limited market appeal and economic logic.

Rather than artificially constraining supply and protecting irresponsible borrowers, we should let nature take its course. Home values need to readjust historic balance between incomes and prices. Over the past 60 years, notes demographer Wendell Cox, it took two to three years or less of median household income to purchase a median-priced home. At the peak of the boom, that ratio had ballooned to 4.6.

The disequilibrium was the worst in regions like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, San Bernardino-Riverside and Miami. At the peak of the bubble, between 2006 and 2008, according to the National Homebuilders Association- Wells Fargo “Housing Opportunity Index,” barely 2% of families with a median income households in Los Angeles could afford to buy a median priced home; even in the traditionally affordable Riverside area, the number was roughly 7%. In Miami, barely 10% could afford such a purchase; in Las Vegas, often seen as one of the cheaper markets, only 15%.

What a difference a market correction makes. The affordability number for Los Angeles is now 34%, 17 times better than two years ago, while Riverside is now near 70%. Miami’s affordability picture has improved to over 60% while in Las Vegas, it’s back over 80%.

These lower prices–not Wall Street or federal gimmickry–will lure new buyers to the places that some new urbanists have predicted will be “the next slums.” Already there’s evidence in places like Miami of a renewed interest in now-affordable suburban single-family homes while condos stay empty or become rentals.

Of course without a return to robust job growth, particularly in the private sector, the home market– and pretty much all mainstream consumer purchases–will remain weak. No matter how low prices get, people worried about losing employment do not constitute a promising new market for homes.

But over the longer run most Americans will seek to purchase homes –whatever the geography. Increasingly this will be less a casino gamble, and more a long-term lifestyle choice. As America adds upwards of 100 million more Americans by 2050, the demand will stare us in the face.

As boomers age, the two big groups that will drive housing will be the young Millenial generation born after 1983 as well as immigrants and their offspring. Sixty million strong, the millenials are just now entering their late 20s. They are just beginning to start hunting for houses and places to establish roots. Generational chroniclers Morley Winograd and Mike Hais, describe millenials in their surveys as family-oriented young people who value homeownership even more than their boomer parents. They also are somewhat more likely to choose suburbia as their “ideal place to live” than the previous generation.

These tendencies are even more marked among immigrants and their children. Already a majority of immigrants live in suburbia, up from 40% in the 1970s. They are attracted in many cases by both jobs and the opportunity to buy a single-family home. For an immigrant from Mumbai, Hong Kong or Mexico City, the “American dream” is rarely living in high density surrounded by concrete; if they wanted that, they could have stayed home.

Over coming generations, changes in family and work life will make single-family homes, townhouses and other moderate-to-low density housing more attractive. Contrary to the anonymity predicted by most futurists, your chosen place is becoming more important, as evidenced by numerous suburban and small town downtown revivals as well as growing local volunteerism.

Equally important, multi-generational households are on the rise back to 1950s levels–in part due to immigrant lifestyle preferences. People are staying put; even before the bubble burst, mobility had dropped to the lowest level in over a half century. With the rise of new technologies allowing for dispersed work, the single family home increasingly houses not only residents, but part and full-time offices.

Barring a long-term permanent recession or a national planning regime aimed at curbing single-family home construction, these factors should lead to a new surge in home buying starting later this decade. It may be too late to save many who overextended themselves in the bubble, but this resurgence could do much to propel our anemic economy, restoring the home to its rightful place one of the cornerstone not only of the American dream, but of our democracy.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.