A year into the Obama administration, America’s dominant geography, suburbia, is now in open revolt against an urban-centric regime that many perceive threatens their way of life, values, and economic future. Scott Brown’s huge upset victory by 5 percent in Massachusetts, which supported Obama by 26 percentage points in 2008, largely was propelled by a wave of support from middle-income suburbs all around Boston. The contrast with 2008 could not be plainer.

Browns’s triumph followed similar wins by Republican gubernatorial contenders last November in Virginia and New Jersey. In those races suburban voters in places like Middlesex County, New Jersey and Loudoun County, Virginia—which had supported President Obama just a year earlier—deserted the Democats in droves. Also in November, voters in Nassau County, New York upset Nassau County Executive Thomas Suozzi, an attractive Democrat who had carefully cultivated suburban voters.

The lesson here is that political movements ignore suburbanites at their peril. For the better part of a century, Americans have been voting with their feet, moving inexorably away from the central cities and towards the suburban periphery. Today a solid majority of Americans live in suburbs and exurbs, more than countryside residents and urbanites combined.

As a result, suburban voters have become the critical determinants of our national politics, culture, and economy. The rise of the Republican majority after 1966 was largely a suburban phenomenon. When Democrats have resurged—as they did under Bill Clinton and again in 2006 and 2008—it was when they came close to splitting the suburban vote.

But now, once again, things have changed. For the first time in memory, the suburbs are under a conscious and sustained attack from Washington. Little that the administration has pushed—from the Wall Street bailouts to the proposed “cap and trade” policies—offers much to predominately middle-income oriented suburbanites and instead appears to have worked to alienate them.

And then there are the policies that seem targeted against suburbs. In everything from land use and transportation to “green” energy policy, the Obama administration has been pushing an agenda that seeks to move Americans out of their preferred suburban locales and into the dense, transit-dependent locales they have eschewed for generations.

As in so many areas, this stance reflects the surprising power of the party’s urban core and the “green” lobby associated with it. Yet, from a political point of view, the anti-suburban stance seems odd given that Democrats’ recent electoral ascendency stemmed in great part from gains among suburbanites. Certainly this is an overt stance that neither Bill nor Hillary Clinton would likely have countenanced.

Whenever possible, the Clintons expressed empathy with suburban and small-town voters. In contrast, the Obama administration seems almost willfully city-centric. Few top appointees have come from either red states or suburbs; the top echelons of the administration draw almost completely on big city urbanites—most notably from Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. They sometimes don’t even seem to understand why people move to suburbs.

Many Obama appointees—such as at the Departments of Transportation and of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—favor a policy agenda that would drive more Americans to live in central cities. And the president himself seems to embrace this approach, declaring in February that “the days of building sprawl” were, in his words, “over.”

Not surprisingly, belief in “smart growth,” a policy that seeks to force densification of communities and returning people to core cities, animates many top administration officials. This includes both HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan and Undersecretary Ron Sims, Transportation undersecretary for policy Roy Kienitz, and the EPA’s John Frece.

Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood revealed the new ideology when he famously declared the administration’s intention to “coerce” Americans out of their cars and into transit. In Congress, the president’s allies, including Minnesota Congressman James Oberstar, have advocated shifting a larger chunk of gas tax funds collected from drivers to rail and other transit.

In addition, the president’s stimulus—with its $8 billion allocation for high-speed rail and proposed giant increases in mass transit—offers little to anyone who lives outside a handful of large metropolitan cores. Economics writer Robert Samuelson, among others, has denounced the high-speed rail idea as “a boondoggle” not well-suited to a huge, multi-centered country like the United States. Green job schemes also seem more suited to boost employment for university researchers and inner-city residents than middle-income suburbanites.

Suburbanites may not yet be conscious of the anti-suburban stance of the Obama team, but perhaps they can read the body language. Administration officials have also started handing out $300 million stimulus-funded grants to cities that follow “smart growth principles.” Grants for cities to adopt “sustainability” oriented development will reward those communities with the proper planning orientation. There is precious little that will benefit suburbanites, such as improved roads or investment in other basic infrastructure.

But ultimately it will be sticks and not carrots that planners hope to use to drive de-suburbanization. Perhaps the most significant will be new draconian controls over land use. Administration officials, particularly from the EPA, participated in the drafting of the recent “Moving Cooler” report, which suggested such policies as charging tolls on the Interstate Highway System, charging people to park in front of their homes, and steering some 90 percent of all future development into the most dense portions of already existing urban development.

Of course, such policies have little or no chance of being passed by Congress. Too many representatives come from suburban or rural districts to back policies that would penalize a population that uses automobiles for upwards of 98 percent of their transportation and account for 95 percent of all work trips.

But the president’s cadres may find other ways to impose their agenda. New controls, for example, may be enacted through the courts and regulatory action. There is already precedence for this: As EPA director under Clinton, current climate czar Carole Browner threatened to block federal funds for the Atlanta region due to their lack of compliance with clear air rules.

Such threats will become more commonplace as regulating greenhouse gases fall under administrative scrutiny. As can already be seen in California, regulators can use the threat of climate change as a rationale to stop funding—and permitting—for even well-conceived residential, commercial, or industrial projects construed as likely to generate excess greenhouse gases.

These efforts will be supported by an elaborate coalition of new urbanist and environmental groups. At the same time, a powerful urban land interest, including many close to the Democratic Party, would also support steps that thwart suburban growth and give them a near monopoly on future development over the coming decades.

Glimpse the Future

One can glimpse this future by observing what takes place in most European countries, including the United Kingdom, where land use is controlled from the center. For decades options for new development have been sharply circumscribed, with mandates for ever-smaller lots and smaller homes more the norm for single-family residences.

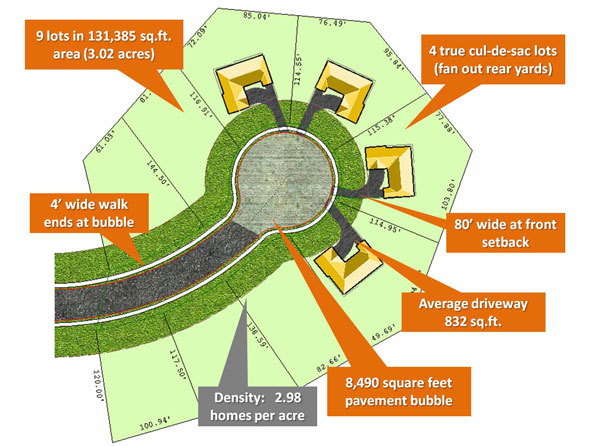

In Britain the dominant planning model is widely known as “cramming,” meaning forced densification into smaller geographic areas. Over the past generation, this has spurred a rapid shrinking of house sizes. Today the average new British “hobbit” house, although quite expensive, covers barely 800 square feet, roughly one-third that of the average American residence. Even in quite distant suburbia many of the features widely enjoyed here—sizable backyards, spare bedrooms, home office space—are disappearing.

But these suburban hobbits will be living large compared to the sardines who would be forced to move into inner cities. In London, already a densely packed city, planners are calling for denser apartment blocks and congested neighborhoods.

This top-driven scenario may be playing soon in America. Following the proposed edicts of “Moving Cooler,” the urban option increasingly would become almost the only choice other than the countryside. Unlike their baby boomer parents, the next generation would have few affordable choices in comfortable, low- and medium-density suburbs and single-family homes.

Ownership of a single-family home would become increasingly the province only of the highly affluent or those living on the fringes of second-tier American cities. Due to the very high costs of construction for multi-family apartments in inner cities, most prospective homeowners would also be forced to remain renters. Although widely hailed as “progressive,” these policies would herald a return to the kind of crowded renter-dominated metropolis that existed prior to the Second World War.

Are Suburbs Doomed?

The anti-suburban impulse is nothing new. Suburbs have rarely been popular among academics, planners, and the punditry. The suburbanite displeased “the professional planner and the intellectual defender of cosmopolitan culture,” noted sociologist Herbert Gans. The 1960s counterculture expanded this critique, viewing suburbia as one of many “tasteless travesties of mass society,” along with fast and processed food, plastics, and large cars. Suburban life represented the opposite of the cosmopolitan urban scene; one critic termed it “vulgaria.”

Liberals also castigated suburbs as the racist spawn of “white flight.” But more recently, environmental causes—particularly greenhouse gas emissions as well as dire warning about the prospects for “peak oil”—now drive much of the argument against suburbanization.

The housing crash that began in 2007 added grist to the contention that the age of suburban growth has come to an end. To be sure, the early phases of the subprime mortgage bust were heavily concentrated in newer developments in the outer fringes. In part due to rising home prices, a disproportionate number of new buyers were forced to resort to sub-prime and other unconventional mortgages.

The outer suburban distress attracted much media attention and delighted many who had long detested suburbs. One leading new urbanist, Chris Leinberger, actually described suburban sprawl as “the root cause of the financial crisis.” Leinberger and other critics have described suburbia as the home of the nation’s future “slums.” The favorite images have included McMansions being taken over by impoverished gang-bangers and other undesirables once associated with the now pristine inner city.

Others portray future suburbs as serving at best as backwaters in a society dominated by urbanites. In contrast to a brave new era for “the gospel of urbanism,” the suburbs are expected to contract and even wither away. According to planner Arthur C. Nelson’s estimate, by 2025 the United States will have a “likely surplus of 22 million large lot homes”—that is, residences on more than one sixth of an acre.

City boosters, however, largely ignore the real-estate crisis impact on urban condo markets throughout the country. Like the new developments on the fringe, the much hyped apartment complexes in central cities such as New York, Miami, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Denver came on line precisely as the housing market crashed, with similar devastating effects. Many remain unoccupied and others have been converted from high-end condos to more modest rentals.

Yet fundamentally the attack on suburbia has less to do with market trends or the environment than with a deep-seated desire to change the way Americans live. For years urban boosters have proposed that more Americans should reside in what they deemed “more livable,” denser, transit-oriented communities for their own good. One recent example, David Owens’ Green Metropolis, supports the notion that Americans should be encouraged to embrace “extreme compactness”—using Manhattan as the model.

Convinced Manhattanization is our future, some “progressives” are already postulating what to do with the remnants of our future abandoned. Grist, for example, recently held a competition about what to do with dying suburbs that included ideas such as turning them into farms, bio-fuel generators, and water treatment plants.

What Do the Suburbanites Want?

In their assessments, few density advocates bother to consider whether most suburbanites would like to give up their leafy backyards for dense apartment blocks. Many urban boosters simply could not believe that, once given an urban option, anyone would choose to live in suburbia.

Jane Jacobs, for example, believed that “suburbs must be a difficult place to raise children.” Yet had Jacobs paid as much attention to suburbs as she did to her beloved Greenwich Village, she would have discovered that they possess their own considerable appeal, most particularly for people with children. “If suburban life is undesirable,” noted Gans in 1969, “the suburbanites themselves seem blissfully unaware of it.”

Contrary to much of the current media hype, most Americans continue to prefer suburban living. Indeed for four decades, according to numerous surveys, the portion of the population that prefers to live in a big city has consistently been in the 10 to 20 percent range, while roughly 50 percent or more opt for suburbs or exurbs. The reasons? The simple desire for privacy, quiet, safety, good schools, and closer-knit communities. The single-family house, detested by many urbanists, also exercises a considerable pull. Surveys by the National Association of Realtors and the National Association of Home Builders find that some 83 percent of potential buyers prefer this kind of dwelling over a townhouse or apartment.

In other words, suburbs have expanded because people like them. A 2008 Pew study revealed that suburbanites displayed the highest degree of satisfaction with where they lived compared to those who lived in cities, small towns, and the countryside. This contradicts another of the great urban legends of the 20th century—espoused by urbanists, planning professors, and pundits and portrayed in Hollywood movies—that suburbanites are alienated, autonomous individuals, while city dwellers have a deep sense of belonging and connection to their neighborhoods.

Indeed on virtually every measurement—from jobs and environment to families—suburban residents express a stronger sense of identity and civic involvement with their communities than those living in cities. One recent University of California at Irvine study found that density does not, as is often assumed, increase social contact between neighbors or raise overall social involvement. For every 10 percent reduction in density, the chances of people talking to their neighbors increases by 10 percent, and their likelihood of belonging to a local club by 15 percent.

These preferences have helped make suburbanization the predominant trend in virtually every region of the country. Even in Portland, Oregon, a city renowned for its urban-oriented policy, barely 10 percent of all population growth this decade has occurred within the city limits, while more than 90 percent has taken place in the suburbs over the past decade. Ironically, one contributing factor has been the demands of urbanites themselves, who want to preserve historic structures and maintain relatively modest densities in their neighborhoods.

Multicultural Flight

Perhaps nothing reflects the universal appeal of suburban lifestyles more than its growing ethnic diversity. In 1970 nearly 95 percent of suburbanites were white. Today many of these same communities have emerged as the new melting pots of American society. Along with immigrants, African-Americans have moved to the suburbs in huge numbers: between 1970 and 2009, the proportion of African-Americans living in the periphery grew from less than one-sixth to 40 percent.

Today minorities constitute over 27 percent of the nation’s suburbanites. In fast-growing Gwinett County outside Atlanta, minorities made up less than 10 percent of the population in 1980; by 2006 the county was on the verge of becoming “majority minority.” In greater Washington, D.C., the Northeast’s most dynamic region in economic and demographic terms, 87 percent of foreign migrants live in the suburbs, while less than 13 percent live in the district, according to a 2001 Brookings Institution study.

Perhaps most intriguingly, this diversity is itself diverse, including not only African-Americans but also Latinos and Asians. Suburban areas such as Fort Bend county, Texas, and the city of Walnut, in the San Gabriel Valley east of Los Angeles, already have among the most diverse populations in the nation. And this is not merely a California phenomenon: Aurora (outside Denver), Bellevue (the Seattle suburb), and Blaine (outside Minneapolis) are becoming ever-more diverse even as the nearby city centers become less so. By 2000 well over half of mixed-race households were in the suburbs, a percentage that continues to grow.

Today the most likely locale for America’s new ethnic shopping centers, Hindu temples, and new mosques are not in the teeming cities but in the outer suburbs of Los Angeles, New York, and Houston. “If a multiethnic society is working out in America,” suggests California demographer James Allen, “it will be worked out in [these] places . . . The future of America is in the suburbs.”

A War Not Worth Fighting

If most Americans clearly prefer suburbs then why would our elected representatives choose to pick a fight with them? Perhaps the most widely used explanation lies with densification as a means of reducing greenhouse gases. But this rationale itself seems flawed, and could reflect more long-standing prejudice than proven science.

For example, a recent study by the National Academy of Sciences found that a nationally imposed densification policy would at best cut greenhouse gas emissions between less than 1 and 11 percent by 2050. Other research suggests that, by some measurements, low-density development can use less energy than denser urban forms.

Although automobile commuting now consumes more energy resources than well-traveled traditional urban rail systems, the future generation of low-mileage cars may prove more efficient than often underutilized rail systems that are now seen as critical elements of fighting climate change. A public system running at low capacity—commonplace in many regions—may actually produce more emissions than the coming generation of personal vehicles.

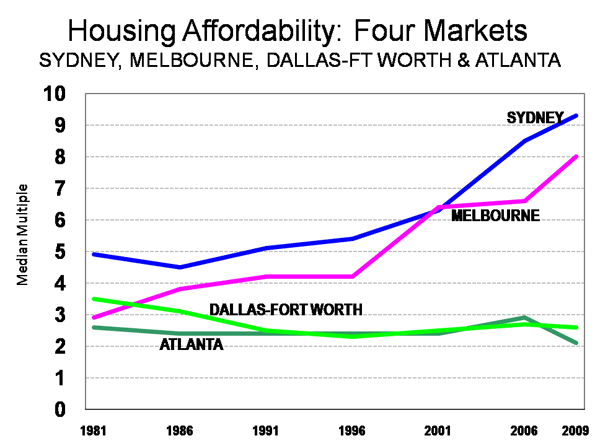

Moreover, tall buildings may not be as green as some advocates suggest. Recent studies out of Australia show that townhouses, small condos, and even single-family homes generate far less heat per capita than the supposedly environmentally superior residential towers, particularly when one takes into account the cost of heating common areas and the highly consumptive lifestyle of affluent urbanites (with their country homes, vacations, and frequent flying). In terms of energy conservation, the easiest and least expensive option may be to retrofit single-family houses and wood-shaded townhouses.

Two- or three-story homes or townhouses often require only double-paned windows and natural shading to reduce their energy consumption; one Los Angeles study found that white roofs and shade trees can reduce suburban air conditioning by 18 percent. Such structures are particularly ideal for using the heat- and water-saving elements of landscaping: after all, a nice maple can cool a two-story house more efficiently than it can a ten-story apartment.

Of course, density advocates can and do produce their own studies to justify their agenda. But there seems enough reasonable doubt to focus on more efficient, and less intrusive, ways to create greener communities by improving energy efficiency of automobiles and changing the way suburbs fit into metropolitan systems.

Turning Deadwood into Greenurbia

The “green” assault on suburbia also largely ignores changes already taking place across the suburban landscape. In a historical context, the latest suburban “sprawl” may be compared to Deadwood. That rough-and-ready mining town on the Dakota frontier was developed quickly for the narrow purpose of being close to a vein of gold. But over time these towns developed respectable shopping streets, theaters, and other community institutions.

One change already evident can be seen in commuting patterns. Density advocates and the media often characterize suburbanites as people who generally take long commutes to work compared to the shorter rides enjoyed by city-dwellers. But with the continuing dispersion of work to the suburbs over the past two decades, suburban work locations actually enjoyed shorter commutes than their inner city counterparts in virtually all the largest metropolitan areas.

This is true even in New York. Although Manhattanites enjoy short commutes and can even walk to work, most people who live in New York City and work in Manhattan suffer among the longest commutes in the nation. In fact, residents of Queens and Staten Island spend the most time getting to work of all metropolitan counties. Residents in suburbs and particularly exurbs actually endure generally shorter commutes, in large part because of less congestion and closer proximity to employment.

Such pairing of jobs and housing will shape the suburban future and represents among the easiest ways to cut transportation-related emissions. Even more promising has been the continuing rise in home-based employment. According to Forrester Research, roughly 34 million Americans now commute at least part time from home; by 2016 these numbers are predicted to swell upwards to 63 million.

Oddly, despite these tremendous potential environmental benefits, the shift toward cyberspace has elicited little support from smart-growth advocates. Indeed most reports on density and greenhouse gases virtually ignore the consideration of telecommuting and dispersed work.

One reason may be that telecommuting breaks with the prevailing planning and green narratives by making dispersion more feasible. The ability to work full time or part time from home, notes one planning expert, expands metropolitan “commuter sheds” to areas well outside their traditional limits. In exchange for a rural or exurban lifestyle, this new commuter—who may go in to “work” only one or two days a week—will endure the periodic extra long trip to the office.

Yet although it may offend planning sensibilities, the potential energy savings—particularly in vehicle miles traveled—could be enormous. Telecommuters drive less, naturally; on telecommuting days, average vehicle miles are between 53 percent and 77 percent lower. Overall a 10 percent increase in telecommuting over the next decade will reduce 45 million tons of greenhouse gases, while also dramatically cutting office construction and energy use. Only an almost impossibly large shift to mass transit could produce comparable savings.

Ultimately, technology will undermine much of the green case against suburbia. If we really want to bring about a greener era, focusing attention on low-density enclaves would bring change that conforms to the preferences of the vast majority of people.

Think Twice Before You Act

Ultimately, the war against suburbia reflects a radical new vision of American life which, in the name of community and green values, would reverse the democratizing of the landscape that has characterized much of the past 50 years. It would replace a political economy based on individual aspiration and association in small communities, with a more highly organized, bureaucratic, and hierarchical form of social organization.

In some ways we could say forced densification could augur in a kind of new feudalism, where questions of land ownership and decision making would be shifted away from citizens, neighbors, or markets, and left in the hands of self-appointed “betters.” This seems strange for an administration—and a party—whose raison d’être ostensibly has been to widen opportunities rather than constrict them.

Indeed it is one of the oddest aspects of contemporary “progressive” thought that it seeks to undermine even modest middle class aspirations such as living in a quiet neighborhood or a single-family house. This does not seem a winning way to build political support across a broad spectrum of the populace.

Of course suburbia is not and will not be the option for everyone. There will continue to be a significant, perhaps even growing, segment of the population which opts for a dense urban lifestyle or, for that matter, to live further in the countryside. But unless we see a radical change in human behavior and social organization, the majority will likely settle for a suburban or exurban existence.

Given these realities, it seems more practical not to work against such aspirations but instead to evolve intelligent policies that would reconcile them with our long-term environmental needs. Suburbanites like their suburbs but would also like to find a way to make them greener as well as more economically and socially viable. Right now neither party has developed such an agenda, and so the suburbs, now clearly leaning right, remain up for grabs. To win suburbanites over, politicians first have to respect the basic preferences while offering a realistic program for improvement. This remains a key to building a sustainable electoral majority, not just for the next election, but for the decades to come.

This article first appeared at The American.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History . His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050 , released in Febuary, 2010.

, released in Febuary, 2010.

(Random/Harmony 2010).