California may yet be a civilization that is too young to have produced its Thucydides or Edward Gibbon, but if it has, the leading candidate would be Kevin Starr. His eight-part “Dream” series on the evolution of the Golden State stands alone as the basic comprehensive work on California. Nothing else comes remotely close.

His most recent volume, “Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963 ,” covers what might be seen as the state’s true Golden Age. To be sure, there is some intriguing history before—the evolution of Hollywood in the 1920s, the reaction to the Depression and the fevered buildup during the Second World War—but this was California’s great moment, its Periclean peak or Augustan age.

,” covers what might be seen as the state’s true Golden Age. To be sure, there is some intriguing history before—the evolution of Hollywood in the 1920s, the reaction to the Depression and the fevered buildup during the Second World War—but this was California’s great moment, its Periclean peak or Augustan age.

“It was a time of growth and abundance,” Starr writes in his preface, and provides the numbers to prove it. In 1950, California was home to 10.7 million, making it a large state to be sure, but hardly a dominant one. By the early 1960s, the population passed 16 million, slipping by New York state in population.

Yet it was not a mere matter of numbers that made California so appealing or important. It was the idea of California as not only a part of America, but also something more. To millions in America and around the world, California grew to mean opportunity, sunshine and innovation.

The state’s business elite, for example, did not identify with the button-down hierarchy that sat atop teeming New York, and its second-tier competitors like Chicago. The leaders of Los Angeles would never consider it a second city, but simply a different, and generally, better one. There was no need for the excessive Manhattan penis envy that led Chicago to keep trying to build higher buildings than Gotham.

In a different way, San Francisco’s top executives also did not crave that their city be New York—it was always more beautiful, nuttier, freer and more creative than Gotham. What they shared with their downstate rivals was a sense of superiority over the old part of the country. If anything, they felt a mixture of contempt—particularly the conservatives—and condescension about an older, decaying society that fixated on tradition, order and breeding.

“California,” Cyril Magnin, scion of one of San Francisco’s great families, told me back in the late 1970s, “has recaptured what America once had—the spirit of pioneering. People in business out here are creative; they’re willing to take risks.”

Geography also plays a role here. Leaders in California, starting at least by the turn of the last century, looked out across the Pacific and saw themselves as part of an emerging shift from Europe to Asia, a process that continues and will dominate the rest of this century. This connection, suggested Pete Hannaford, a public relations executive and partner of Ronald Reagan’s Svengali, Michael Deaver, took on an almost Spenglerian inevitability. “Out here there’s a sense of being where the action is,” Hannaford believed, “with Japan and the Pacific.”

Starr captures these attitudes, which already had become deeply entrenched by the late 1950s and early 1960s. There was, as he writes, “a conviction that California was the best place to seek and attain a better American life.” However, it was more than money or power. It was about the quality of life. Success in California was not a matter of living by the rules, sheltered in a dark Manhattan apartment, but about the seduction of the physical world. In California, Starr writes, “Eros vanquished Thanatos.”

Yet Starr’s book is not merely about the rich, the powerful, and even the culturally influential. He finds his primary muse not in the Bohemian realms of San Francisco or the mansions of Beverly Hills, but in that most democratic of everyman’s places, the San Fernando Valley, the place author Kevin Roderick aptly dubbed “America’s Suburb.”

To see long excerpts from “Golden Dreams,” click here.

“The Valley” lies over the Santa Monica Mountains from the Los Angeles Basin. As late as the 1930s, it was largely an arid district of ranches, citrus orchards and chicken farms. The area’s postwar expansion was rapid, even by California standards. Between 1945 and 1950 alone, the Valley’s population more than doubled to nearly 500,000. By 1960, it had doubled again.

This growth was far more than the mindless bedroom sprawl often depicted by aesthetes and urban intellectuals. People in the Valley did not depend largely on the old part of Los Angeles the way, for example, Long Island lived off Manhattan. Most of the Valley’s growth was homegrown—driven by local industry such as aerospace, entertainment, electronics and until the 1960s automobiles.

Even today, the Valley has very much its own economy and sense of separation from Los Angeles. However, more important, the Valley was, first, a middle-class phenomenon. A cosmopolitan of the first order, Starr manages to chronicle California’s artistic and literary elites, but does not see in them the essence of the state’s appeal. Instead, he explores the everyday wonders of the Valley’s families, single-family homes and swimming pools—6,000 permitted in one year, between 1959 and 1960!

As a Valley resident myself, I can still see the basic imprint of that culture, what Starr calls its “way of life.” Compared to the tony Westside and hardscrabble east and southside of Los Angeles, the Valley has remained a relatively safe “child-oriented” society, with a big emphasis on restaurants, malls, ball fields, churches and synagogues.

The single-family tracts, of course, have changed hands, and the majority of the owners have changed. The primarily WASP and second-generation Eastern European Jews are still there, but they have steadily been augmented, and sometimes outnumbered, by others—Armenians, Orthodox Jews, Israelis, Persians, Thais, Chinese, Mexicans, Salvadorans, African-Americans and at least 10 groups I somehow will neglect and no doubt offend.

Yet the essential way of life forged in the 1950s and 1960s has remained a constant, and that remains the source of California’s attraction. Of course, it is no longer just a “Valley” phenomenon. As California has grown, there are many such places, outside San Diego, in Orange County, the Inland Empire, outside Sacramento, Fresno and scores of other towns. Almost all have the same imprint—an auto-dominated culture, dispersed workplaces, pools and a culture of aspiration.

In the ensuing decades, perhaps to be covered in Starr’s next book, this archetype evolved mightily. The San Gabriel Valley, once a plain vanilla suburban appendage, has morphed into the country’s largest Asian suburbia, complete with a shopping center jokingly referred to as “the Great Mall of China.” The often-monotonous housing tracts between San Jose and Palo Alto, on the San Francisco Peninsula, also attracted hundreds of thousands of Asians but also produced something equally astounding—the Silicon Valley, the world’s leading center for technology.

These suburban developments long ago surpassed in importance the urban roots of California metropolises. A serious corporate center during the time covered by Starr’s volume, San Francisco has devolved in a ultra-politically correct, hip and cool urban Disneyland for Silicon Valley, providing good restaurants and housing for those still too young to crave a house on the Peninsula. The San Gabriel Chinatown long ago replaced the older one in downtown Los Angeles as the center of Asian culture and cuisine.

These places grew before the current malaise infected the state. As Starr points out, California based its ascendancy on two seemingly contradictory principles: entrepreneurship and activist government. Under Gov. Earl Warren, but also Goodwin Knight and finally Pat Brown, the state made a commitment both to basic infrastructure—energy, water, roads, schools, parks—and expanding its economy.

By the early 1960s, this system was hitting on all cylinders. New roads, power plants and water systems opened lands for development for farms, subdivisions, factories. Ever expanding and improving schools produced a work force capable of performing higher-end tasks, and capable of earning higher wages. New parks preserved at least some of the landscape, and gave families a place to recreate.

For Pat Brown, arguably the greatest governor in American history, this was all part of California’s “destiny.” Starr describes Brown’s California as “a modernist commonwealth, a triumph of engineering, a megastate committed to growth as its first premise.” Yet within this great modernist project was also stirring opposition, on both left and right, that would soon place this Golden Age at its end.

Many of the objections were legitimate. The Sierra Club and its many spinoffs rightfully saw the Brown development machine as threatening California’s landscape, wildlife and, in important ways, the appeal of its way of life. More careful controls on growth clearly were needed. The battle over the nature of those controls continues to this day.

Some more angry voices, then as now, targeted the very existence of suburbia, the dominant form of the state’s growth, and eventually sought its eradication. This struggle goes on to this day with a religious fervor, led, ironically, by the former and perhaps future governor, Jerry Brown, currently attorney general and leading Torquemada of the greens.

Minorities also began to stir amid the celebrations of the 1950s and early 1960s. Woefully underrepresented in the halls of power and the corridors of business, Asians and Latinos remained largely passive politically. However, by the early 1960s acceptance of exclusion was giving way to more assertive attitudes. Ultimately the massive immigration that swelled both their numbers in the 1970s and beyond would ensure these groups far more influence both on the politics and in the economy of the state.

Yet it was the African-American who would really upset the balance of the golden era. Never discriminated against as in the South, black Californians felt the lash of a thousand, often-informal exclusions. As the civil rights movement grew, with it less deferential attitudes, particularly toward the police, a powder keg was building. In 1964, the first year after the era chronicled in “Golden Dreams,” Watts blew up, shattering the comfortable assumptions of a progressive, post-racial state.

Finally, as Starr reports, there was mounting thunder on the right. The business elite and the middle class were financing the ever-expanding California state. They saw their money go to the poor, to minorities and state employees. Particularly annoying were the university students, many of whom were in open revolt against the state, in the mind of much of the public that had nurtured them.

By the early 1960s many of these latter Californians also were angry, but their rage would express itself not in riots, but at the ballot box, ushering in the age of Ronald Reagan. The period that follows “Golden Dreams” emerges as one of conflicting visions, between greens, students and minorities, on the one hand, and largely suburban middle-class workers and business owners on the other.

These two groups would battle over the next generation, with the advantage oscillating over time. Today the heirs of the protesters—greens, minority activists and former ’60s radicals—hold the political advantage, although the state they dominate has fallen on parlous times.

In retrospect, the golden era before these conflicts does indeed seem like a high point. The question now is whether California, down on its luck, will find a way to rebound, much as imperial Rome did after the demise of the Julian dynasty, or fall, like Athens, into ever more squalid decline. Does the state have a bright “destiny” ahead or only more ruin?

This, of course, will be the basis for another historical epoch. Let us hope Kevin Starr be around to chronicle it for the rest of us.

This piece originally appeared at Truthdig.com

Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963 at Amazon.com.

at Amazon.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History . His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.

. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.

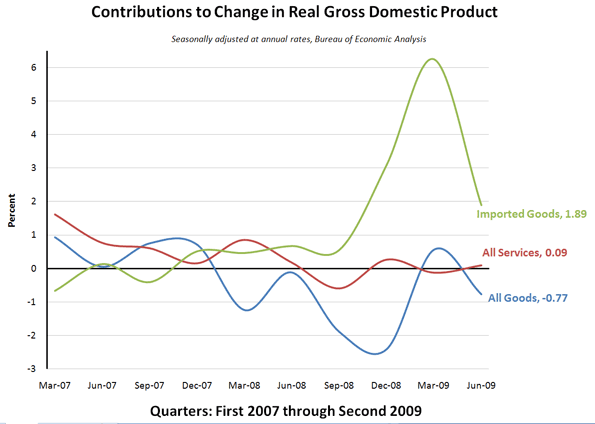

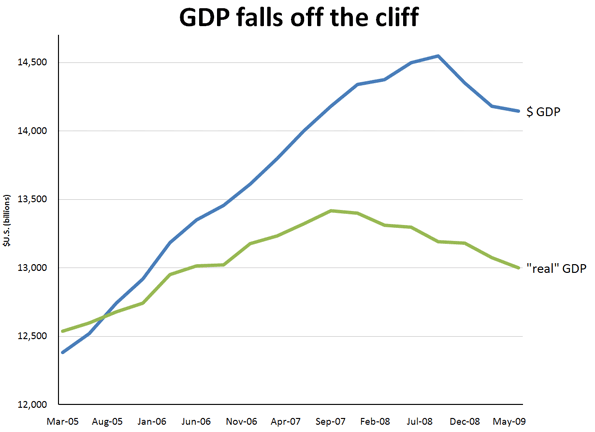

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations

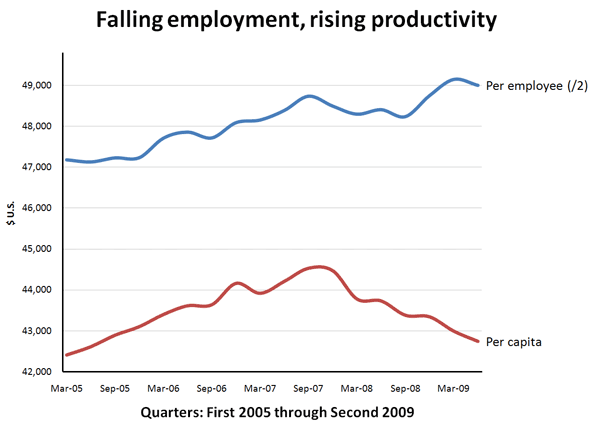

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Census Bureau. Per employee divided by 2 for scale.

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Census Bureau. Per employee divided by 2 for scale.