In my first foray into political life in the 1970s, I worked during college on the staff of a liberal Democrat in the Texas state Senate. Only a few years earlier, Patty Hearst had been kidnapped and brainwashed by the Symbionese Liberation Army, and a moral panic about cults seducing college kids was sweeping the nation. One result was the rise of a new, thankfully ephemeral profession: “deprogrammers” who for pay would kidnap a young person from a cult and break the spell, by means of isolation, interrogation and maybe reruns of “The Waltons.”

A reactionary Republican state senator from the Houston area, who was heartily despised by my senator, introduced a bill granting parents the right to hire deprogrammers to kidnap adult children who belonged to what the parents regarded as cults and then confine them in motels for several weeks, subject to psychological coercion, without notifying the authorities. Needless to say, this deprogramming law was the greatest threat to the tradition of habeas corpus until another reactionary Texan was installed in the White House in 2001. The bill was laughed to death, when, during a hearing, the sponsor was asked if it could be used to deprogram young people who had joined a certain well-known cult. “Why, yes, Senator,” the Republican replied, “it would apply to cults like the Unitarians.”

Boy, do we need deprogrammers now, to liberate Barack Obama from the cult of neoliberalism.

By neoliberalism I mean the ideology that replaced New Deal liberalism as the dominant force in the Democratic Party between the Carter and Clinton presidencies. In the Clinton years, this was called the “Third Way.” The term was misleading, because New Deal liberalism between 1932 and 1968 and its equivalents in social democratic Europe were considered the original “third way” between democratic socialism and libertarian capitalism, whose failure had caused the Depression. According to New Deal liberals, the United States was not a “capitalist society” or a “market democracy” but rather a democratic republic with a “mixed economy,” in which the state provided both social insurance and infrastructure like electric grids, hydropower and highways, while the private sector engaged in mass production.

When it came to the private sector, the New Dealers, with some exceptions, approved of Big Business, Big Unions and Big Government, which formed the system of checks and balances that John Kenneth Galbraith called “countervailing power.” But most New Dealers dreaded and distrusted bankers. They thought that finance should be strictly regulated and subordinated to the real economy of factories and home ownership. They were economic internationalists because they wanted to open foreign markets to U.S. factory products, not because they hoped that the Asian masses some day would pay high overdraft fees to U.S. multinational banks.

New Dealers approved of social insurance systems like Social Security and Medicare, which were rights (entitlements) not charity and which mostly redistributed income within the middle class, from workers to nonworkers (the retired and the temporarily unemployed). But contrary to conservative propaganda, New Deal liberals disliked means-tested antipoverty programs and despised what Franklin Roosevelt called “the dole.” Roosevelt and his most important protégé, Lyndon Johnson, preferred workfare to welfare. They preferred a high-wage, low-welfare society to a low-wage, high-welfare society. To maintain the high-wage system that would minimize welfare payments to able-bodied adults, New Deal liberals did not hesitate to regulate the labor market, by means of pro-union legislation, a high minimum wage, and low levels of immigration (which were raised only at the end of the New Deal period, beginning in 1965). It was only in the 1960s that Democrats became identified with redistributionist welfarism — and then only because of the influence of the New Left, which denounced the New Deal as “corporate liberalism.”

Between the 1940s and the 1970s, the New Deal system — large-scale public investment and R&D, regulated monopolies and oligopolies, the subordination of banking to productive industry, high wages and universal social insurance — created the world’s first mass middle class. The system was far from perfect. Southern segregationist Democrats crippled many of its progressive features and the industrial unions were afflicted by complacency and corruption. But for all its flaws, the New Deal era is still remembered as the Golden Age of the American economy.

And then America went downhill.

The “stagflation” of the 1970s had multiple sources, including the oil price shock following the Arab oil embargo in 1973 and the revival of German and Japanese industrial competition (China was still recovering from the damage done by Mao). During the previous generation, libertarian conservatives like Milton Friedman had been marginalized. But in the 1970s they gained a wider audience, blaming the New Deal model and claiming that the answer to every question (before the question was even asked) was “the market.”

The free-market fundamentalists found an audience among Democrats as well as Republicans. A growing number of Democratic economists and economic policymakers were attracted to the revival of free-market economics, among them Obama’s chief economic advisor Larry Summers, a professed admirer of Milton Friedman. These center-right Democrats agreed with the libertarians that the New Deal approach to the economy had been too interventionist. At the same time, they thought that government had a role in providing a safety net. The result was what came to be called “neoliberalism” in the 1980s and 1990s — a synthesis of conservative free-market economics with “progressive” welfare-state redistribution for the losers. Its institutional base was the Democratic Leadership Council, headed by Bill Clinton and Al Gore, and the affiliated Progressive Policy Institute.

Beginning in the Carter years, the Democrats later called neoliberals supported the deregulation of infrastructure industries that the New Deal had regulated, like airlines, trucking and electricity, a sector in which deregulation resulted in California blackouts and the Enron scandal. Neoliberals teamed up with conservatives to persuade Bill Clinton to go along with the Republican Congress’s dismantling of New Deal-era financial regulations, a move that contributed to the cancerous growth of Wall Street and the resulting global economic collapse. As Asian mercantilist nations like Japan and then China rigged their domestic markets while enjoying free access to the U.S. market, neoliberal Democrats either turned a blind eye to the foreign mercantilist assault on American manufacturing or claimed that it marked the beneficial transition from an industrial economy to a “knowledge economy.” While Congress allowed inflation to slash the minimum wage and while corporations smashed unions, neoliberals chattered about sending everybody to college so they could work in the high-wage “knowledge jobs” of the future. Finally, many (not all) neoliberals agreed with conservatives that entitlements like Social Security were too expensive, and that it was more efficient to cut benefits for the middle class in order to expand benefits for the very poor.

The transition from New Deal liberalism to neoliberalism began with Carter, but it was not complete until the Clinton years. Clinton, like Carter, ran as a populist and was elected on the basis of his New Deal-ish “Putting People First” program, which emphasized public investment and a tough policy toward Japanese industrial mercantilism. But early in the first term, the Clinton administration was captured by neoliberals, of whom the most important was Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin. Under Rubin’s influence, Clinton sacrificed public investment to the misguided goal of balancing the budget, a dubious accomplishment made possible only by the short-lived tech bubble. And Rubin helped to wreck American manufacturing, by pursuing a strong dollar policy that helped Wall Street but hurt American exporters and encouraged American companies to transfer production for the U.S. domestic market to China and other Asian countries that deliberately undervalued their currencies to help their exports.

By the time Barack Obama was inaugurated, the neoliberal capture of the presidential branch of the Democratic Party was complete. Instead of presiding over an administration with diverse economic views, Obama froze out progressives, except for Jared Bernstein in the vice-president’s office, and surrounded himself with neoliberal protégés of Robert Rubin like Larry Summers and Tim Geithner. The fact that Robert Rubin’s son James helped select Obama’s economic team may not be irrelevant.

Instead of the updated Rooseveltonomics that America needs, Obama’s team offers warmed-over Rubinomics from the 1990s. Consider the priorities of the Obama administration: the environment, healthcare and education. Why these priorities, as opposed to others, like employment, high wages and manufacturing? The answer is that these three goals co-opt the activist left while fitting neatly into a neoliberal narrative that could as easily have been told in 1999 as in 2009. The story is this: New Dealers and Keynesians are wrong to think that industrial capitalism is permanently and inherently prone to self-destruction, if left to itself. Except in hundred-year disasters, the market economy is basically sound and self-correcting. Government can, however, help the market indirectly, by providing these three public goods, which, thanks to “market failures,” the private sector will not provide.

Healthcare? New Deal liberals favored a single-payer system like Social Security and Medicare. Obama, however, says that single payer is out of the question because the U.S. is not Canada. (Evidently the New Deal America of FDR and LBJ was too “Canadian.”) The goal is not to provide universal healthcare, rather it is to provide universal health insurance, by means that, even if they include a shriveled “public option,” don’t upset the bloated American private health insurance industry.

Education? In the 1990s, the conventional wisdom of the neoliberal Democrats held that the “jobs of the future” were “knowledge jobs.” America’s workers would sit in offices with diplomas on the wall and design new products that would be made in third-world sweatshops. We could cede the brawn work and keep the brain work. Since then, we’ve learned that brain work follows brawn work overseas. R&D, finance and insurance jobs tend to follow the factories to Asia.

Education is also used by neoliberals to explain stagnant wages in the U.S. By claiming that American workers are insufficiently educated for the “knowledge economy,” neoliberal Democrats divert attention from the real reasons for stagnant and declining wages — the offshoring of manufacturing, the decline of labor unions, and, at the bottom of the labor market, a declining minimum wage and mass unskilled immigration. One study after another since the 1990s has refuted the theory that wage inequality results from skill-biased technical change. But the neoliberal cultists around Obama who write his economic speeches either don’t know or don’t care. Like Bill Clinton before him, Barack Obama continues to tell Americans that to get higher wages they need to go to college and improve their skills, as though there weren’t a surplus of underemployed college grads already.

Environment? Here the differences between the New Deal Democrats and the Obama Democrats could not be wider. Their pro-industrial program did not prevent New Deal Democrats from being passionate about resource conservation and wilderness preservation. They did not hesitate to use regulations to shut down pollution. And their approach to energy was based on direct government R&D (the Manhattan Project) and direct public deployment (the TVA).

Contrast the straightforward New Deal approaches with the energy and environment policies of Obama and the Democratic leadership, which are at once too conservative and too radical. They are too conservative, because cap and trade relies on a system of market incentives that are not only indirect and feeble but likely to create a subprime market in carbon, enriching a few green profiteers. At the same time, they are too radical, because any serious attempt to shift the U.S. economy in a green direction by hiking the costs of non-renewable energy would accelerate the transfer of U.S. industry to Asia — and with it not only industry-related “knowledge jobs” but also the manufacture of those overhyped icons of the “green economy,” solar panels and windmills.

While we can’t go back to the New Deal of the mid-20th century in its details, we need to re-create its spirit. But short of confining them in motel rooms and making them watch newsreels about the Hoover Dam, Glass-Steagall, the TVA and the Manhattan Project, is it possible to liberate President Obama and the Democratic leadership from the cult of neoliberalism?

This article first appeared at Salon.com

Michael Lind is Whitehead Senior Fellow at the New America Foundation and Director of the American Infrastructure Initiative.

Official White House Photo by Pete Souza.

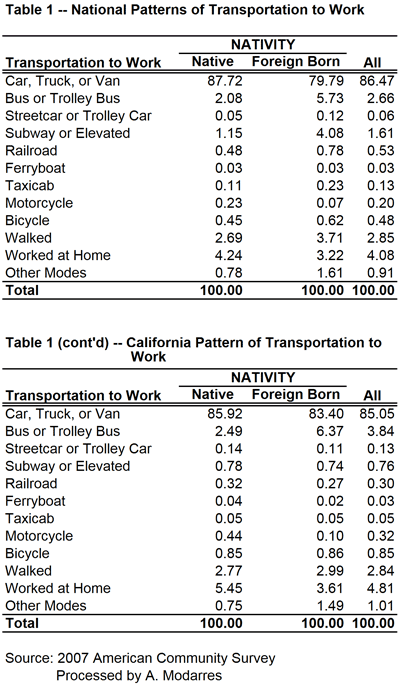

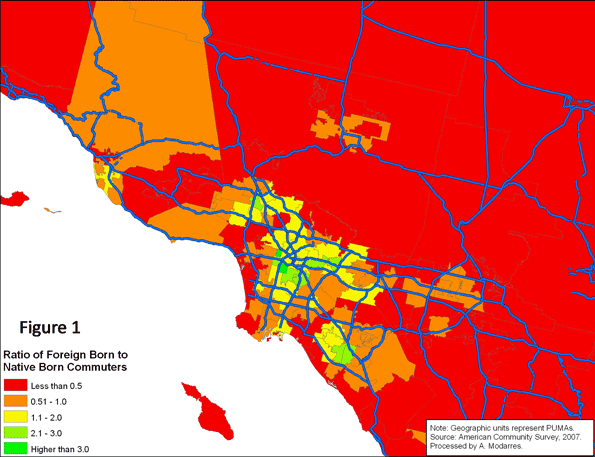

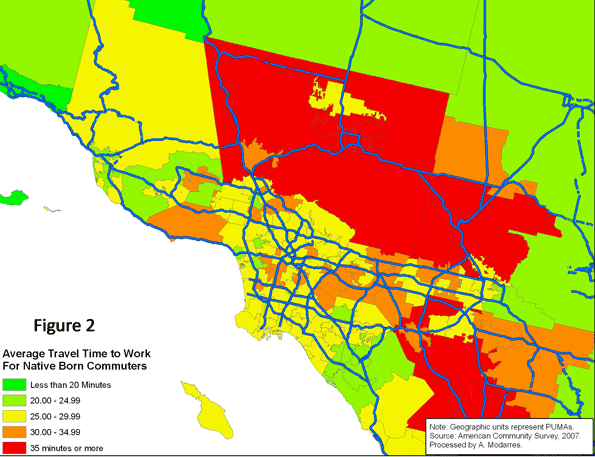

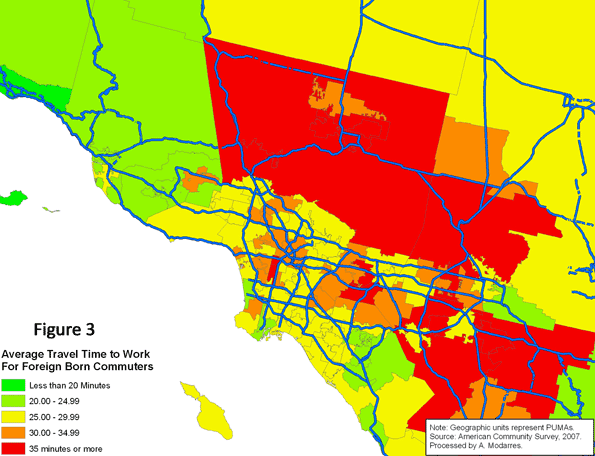

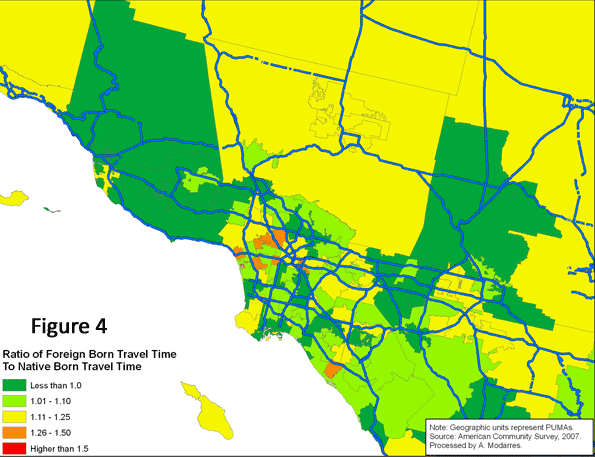

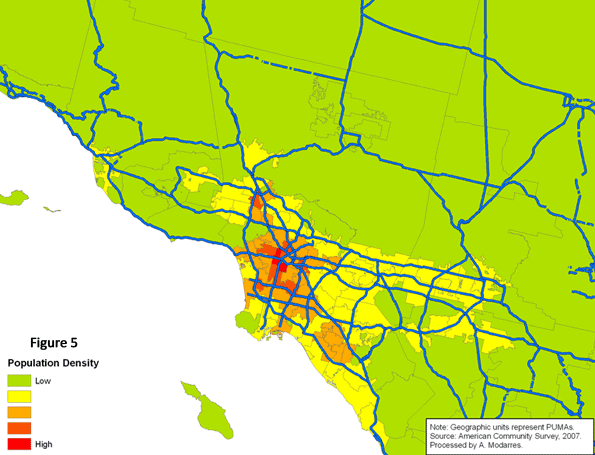

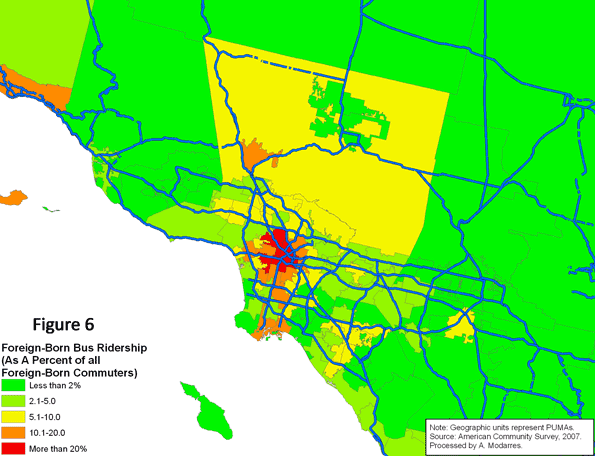

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

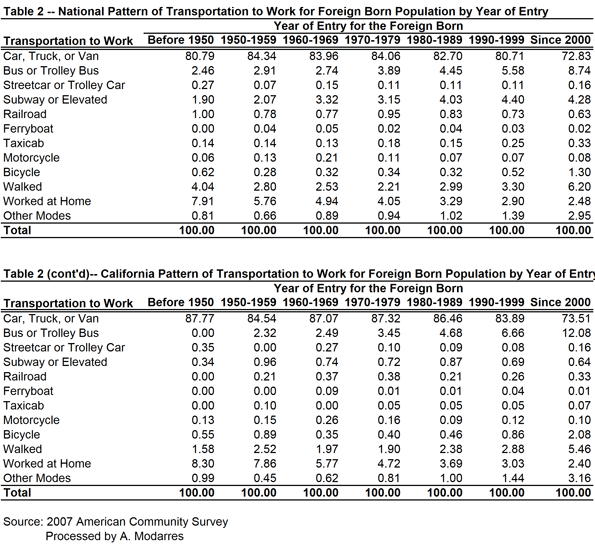

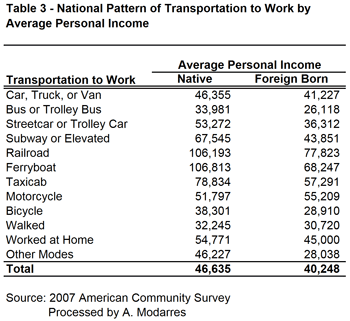

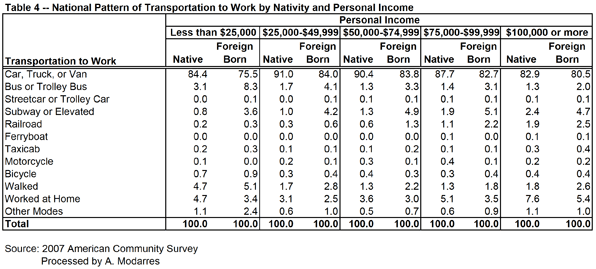

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.

Yet physical public space continues to serve as medium of the new Street Art form. Stickers, tags, skateboards, and tattoos are all viewed on the street, offering a means to carry this new art form into the next century. The so-called “cutting edge” artists have retreated into their private studios to conceive their next moves in video or computers, but the street artists have taken over the city.

Yet physical public space continues to serve as medium of the new Street Art form. Stickers, tags, skateboards, and tattoos are all viewed on the street, offering a means to carry this new art form into the next century. The so-called “cutting edge” artists have retreated into their private studios to conceive their next moves in video or computers, but the street artists have taken over the city.

Graffiti’s barrage of skulls, vacant-eyed cartoon children, and other signs of death and destruction are easy to ignore, but they are telling us something important about the urban environment. The sooner we stop and examine this evidence, the sooner we can begin a process to find common ground, and to seek out a shared vision that does not divide the urban world into an us-and-them mentality. Street art simply puts visual form to the voices we have so long shut out of the urban conversation.

Graffiti’s barrage of skulls, vacant-eyed cartoon children, and other signs of death and destruction are easy to ignore, but they are telling us something important about the urban environment. The sooner we stop and examine this evidence, the sooner we can begin a process to find common ground, and to seek out a shared vision that does not divide the urban world into an us-and-them mentality. Street art simply puts visual form to the voices we have so long shut out of the urban conversation.

The graffiti artists have offered a philosophical change-up that should not be overlooked. The conversation about postmodern art seemed to have reached a dead end some time ago; artists

The graffiti artists have offered a philosophical change-up that should not be overlooked. The conversation about postmodern art seemed to have reached a dead end some time ago; artists