Canaries were used in early coal mines to detect deadly gases, such as methane and carbon monoxide. If the bird was happy and singing, the miners were safe. If the bird died, the air was not safe, and the miners left. The bird served as an early warning system.

Domestic migration trends play a similar early warning system for states. California’s dynamism was always reflected by its ability to attract newcomers to the state. But today California’s canary is dead.

Here’s the logic. If net domestic migration is positive, the state’s economy is reasonably sound. Economic growth, taxes, housing, and amenities are strong enough to keep people where they are and attract others. If net domestic migration is negative, it usually means that lack of economic growth, taxes, quality of life, and housing have deteriorated sufficiently to drive people away. This happens despite the inevitable pain of leaving the security and comfort of family, friends, and familiar surroundings.

California has been a destination for migrating workers and families since 1849. They came form every state and from around the world. Often the migrants faced tremendous challenges and hardship. Illegal immigrants from Mexico and other developing countries still must leap over such barriers. Often, California’s migrants came in waves. The 1850s, 1930s, and 1950s all saw huge surges tied to huge events – the Gold Rush, the Depression and the post-war boom. But even between these waves, California consistently experienced a steady inflow of new immigrants.

Immigration has been good for California. The new residents brought ambition, skills, and a willingness to take risks. They found a state with abundant natural resources, from oil to rich soil and ample, if sometimes distant water resources. Together with the people already there, they created an economic powerhouse. They built cities with amenities that rival any other. They fed much of the nation and large numbers overseas. They did this while persevering much of California’s unique endowment: the vast coastline, the Sierra Nevada, and the deserts.

California, with 12 percent of the United States population, became the world’s sixth largest economy while managing to maintain the aura of paradise at the same time. Opportunity and housing were abundant. California was a great place to have a career and raise a family.

Most recently, though, this has begun to change. California is no longer a preferred destination, at least for domestic migrants. The state’s economy is limping along considerably worse than that of the nation. Opportunity is limited. Housing is relatively expensive, even after the dramatic deflation of the past two years, except for some very hard-hit and generally less attractive inland areas. Taxes are high and increasing. Regulation is onerous and becoming more so. Many California communities are outright hostile to business.

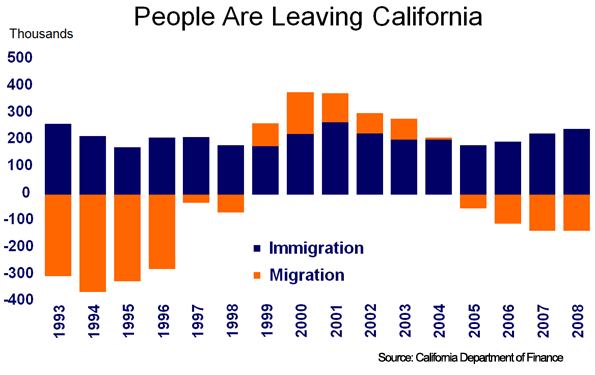

Consequently, net domestic migration has been negative for 10 of the past fifteen years. International migration to California remains positive, but that reflects more on the weakness of the economies and the attraction of existing ethnic networks than the intrinsic superiority of California. This represents a sea change: anyone predicting it fifteen years ago would have been laughed out of the room.

What happened?

California’s economy was badly hit by the 1990s recession. The State’s aerospace and defense sectors were especially decimated. Middle-class families moved out by the hundreds of thousands.

The 1990s out migration caused some soul searching in California. There was lots of talk, and a little action on making the State more competitive. Then came the technology and real estate booms. Domestic migration turned positive. The half-hearted efforts to make California more competitive faded as policy makers were lulled into complacency by the strength of California’s resurgence.

But the problems that bedeviled the state in the 1990s – high housing prices and taxes, cascading regulations and a deteriorated infrastructure – had only been obscured by the boom. By 2005 migration began to turn negative, largely as soaring housing prices discouraged newcomers and encourage many residents to cash out and move to less expensive places. California had priced itself, and the dream, out of competitiveness. Since then, California has seen four consecutive years of increasingly negative domestic migration. The recent net outflow numbers have been smaller than in the 1990s, but it may be because other tradidional California migrant destination economies – like Oregon, Washington, Nevada and Arizona – have become less competitive as well.

Today, many argue that California will bounce back, but they can’t identify the reason. What sector will lead the resurgence? They seem to think economic growth will come with the sunshine, beaches, and mountains. There was plenty of sunshine in the 80 years between the founding of the first mission and the gold rush, and not much happened. Similarly, the differences between California cities and neighboring Mexican cities show clearly that successful economies need more than good looks and nice climate.

It’s hard right now to assume California’s future will include the same predominance in technological innovation. Agriculture is running out of water, in large part due to environmental lawsuits, and the state no longer seems willing to invest in new water projects. Even the entertainment industry is increasingly looking outside of California for growth. You have to ask: what does California offer that will overcome the State’s high costs, regulatory environment, and antipathy to business?

That is the short term. The long term doesn’t look very good either. The public universities, a major source of innovation over the past two decades, are facing increasingly severe budget challenges. It is unlikely that they will be able to maintain their status even as other states – Texas, Colorado, New Mexico – eye further expansion. Even more ominous are gains in countries, such as China and India, who have long sent their best and brightest to the Golden State.

All this suggests a relative decline in California’s long-term prospects. What should we do? Part of California’s problem is its political process. The state’s chronic inability to do much of anything reinforces stasis. As Dan Walters says, “everyone has a veto on everything.”

But even improving the political process may not be enough. Much of Coastal California is dominated by rich, aging, baby boomers. The residents of this increasingly geriatric ghetto often don’t worry much about economic opportunity. They may have the money and votes to guarantee that growth does not impinge on their lifestyles. Unless these conditions change, it will be unlikely to see a renewal of strong domestic migration to California in the coming years.

Bill Watkins, Ph.D. is the Executive Director of the Economic Forecast Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is also a former economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington D.C. in the Monetary Affairs Division.