This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism titled "The Texas Way of Urbanism". Download the entire report here.

The future of American cities can be summed up in five letters: Texas. The metropolitan areas of the Lone Star state are developing rapidly. These cities are offering residents a broad array of choices — from high density communities to those where the population is spread out — and a wealth of opportunities.

Historically, Texas was heavily dependent on commodities such as oil, cotton, and cattle, with its cities largely disdained by observers. John Gunther, writing in 1946, described Houston as having “…a residential section mostly ugly and barren, without a single good restaurant and hotels with cockroaches.” The only reasons to live in Houston, he claimed, were economic ones; it was a city “…where few people think about anything but money.” He also predicted that the area would have a million people by now. Actually, the metropolitan area today is well on the way to seven million.

It would no doubt shock Gunther to learn that Texas now boasts some of the most dynamic urban areas in the high income world. Approximately 80 percent of all population growth since 2000 in the Lone Star state has been in the four largest metropolitan areas. People may wear cowboy boots, drive pickups and attend the big rodeo in Houston, but they are first and foremost part of a great urban experiment.

The notion of Texas as an urban model still rankles many of those who think of themselves as urbanists. Most urbanists, when thinking of cities of the future, keep an eye on the past, identifying with the already great cities that follow the traditional transit dependent and dense urban form: New York, London, Chicago, Paris, Tokyo. And yet, within these five urban areas, there are large, evolving, dynamic sections that are automobile oriented and have lower density.

Measuring Employment Success

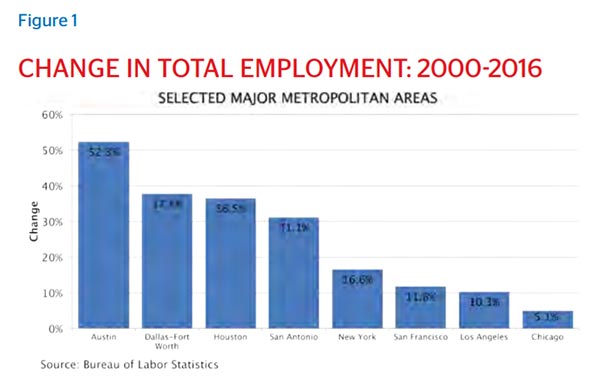

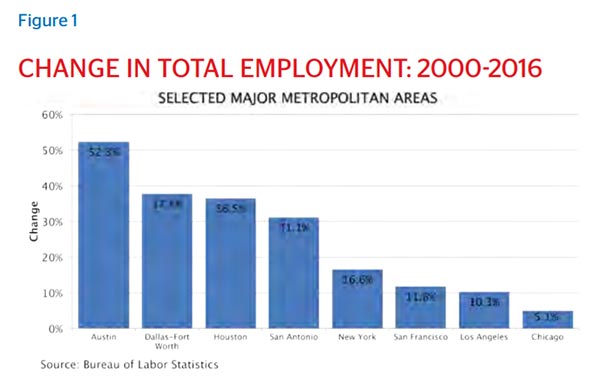

Since 2000, Dallas and Houston have increased jobs by 31 percent, growing at three times the rate of increase in New York and five times as rapidly as Los Angeles. Texas’ smaller but up-and-coming metropolitan regions are also thriving, with San Antonio and Austin, for example, boasting some of the most rapid job growth in the country.

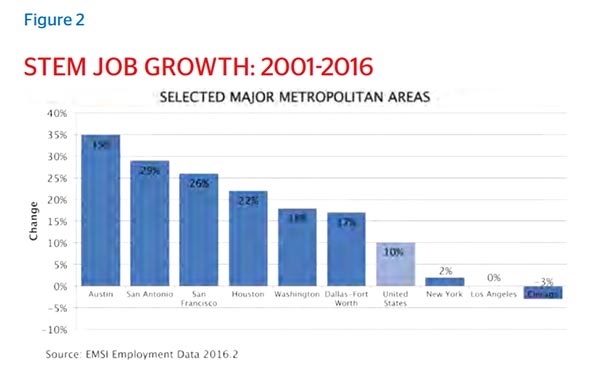

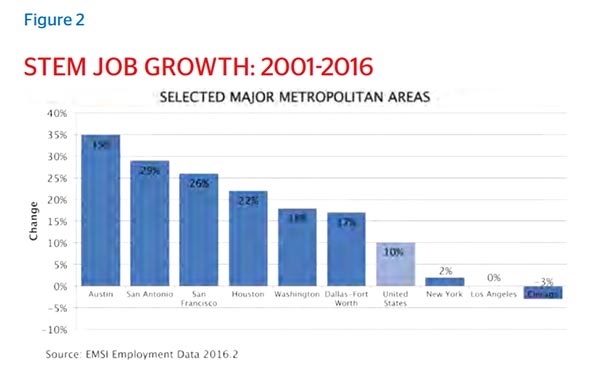

This growth is not all at the low end of the job market, as some suggest. Over the past fifteen years Texas cities have generally experienced faster STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math-related) job growth than their more celebrated rivals. Austin and San Antonio have grown their STEM related jobs even more quickly than the San Francisco Bay Area has grown theirs, while both Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth have increased STEM employment far more rapidly than New York, Los Angeles or Chicago.

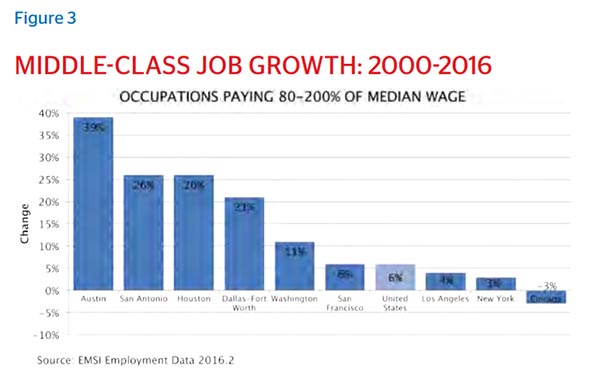

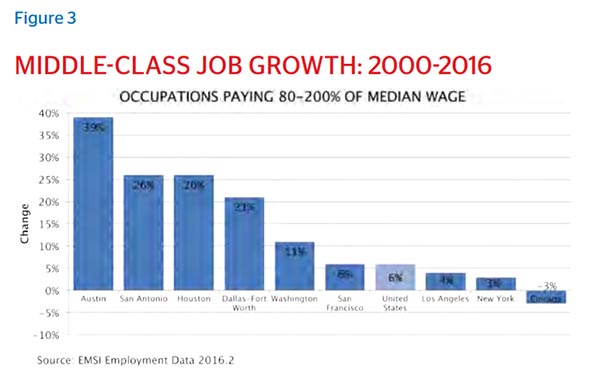

The Texas cities also have enjoyed faster growth in middle class jobs, those paying between 80 percent and 200 percent of the median wage at the national level. Since 2001, these jobs have grown 39 percent in Austin, 26 percent in Houston, and 21 percent in Dallas-Fort Worth, a much more rapid clip than experienced in San Francisco, New York or Los Angeles, while Chicago has actually seen these kinds of job decrease.

Recent Pew Research Center data illustrates that between 2000 and 2014, out of the 53 metropolitan areas with populations of more than 1,000,000, San Antonio had the second largest gain in percentage of combined middle-income and upper-income households; the percentage of households in the lower-income segment dropped. Houston ranked 6th and Austin ranked 13th, while Dallas-Fort Worth placed 25th, still in the top half.

Much of the credit for this growth in jobs goes to the state’s reputation for business friendliness. Texas is consistently ranked by business executives as the first or second leading state. Needless to say, New York, California and Illinois do not fare nearly as well. The Texas tax burden ranks 41st in the country. Compare this to New York, which has the highest total state tax burden, Texas rates are also far lower than those in New York, neighbors Connecticut and New Jersey, or in California.

The Demographic Equation

No surprise, then, that people are flocking to the Texas cities. Over the last ten years, Dallas-Ft. Worth and Houston have emerged as the fastest growing big cities of more than five million people in the high-income world, growing more than three times faster in population than New York, Chicago, Los Angeles or Boston. Among the 53 US major metropolitan areas, four of the top seven fastest growing from 2010 to 2015 were in Texas.

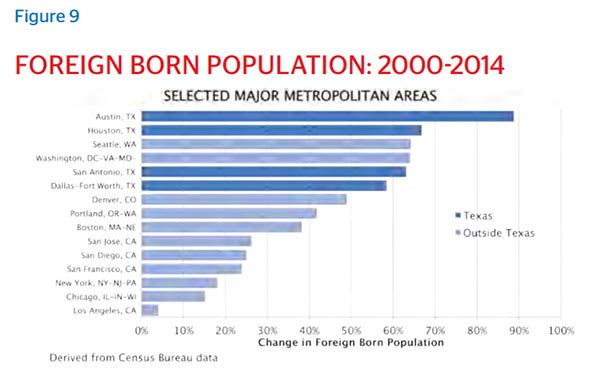

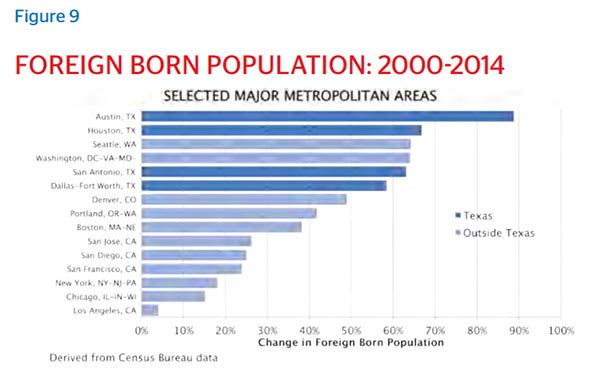

Foreign immigration, a key indicator of economic opportunity, is now growing much faster in Texas’ cities than in those of its more established rivals. Between 2000 and 2014 alone, Texas absorbed more than 1.6 million foreign born citizens. In numbers, that’s slightly less than California took in, but in proportion to Texas’ population it is 60 percent more.

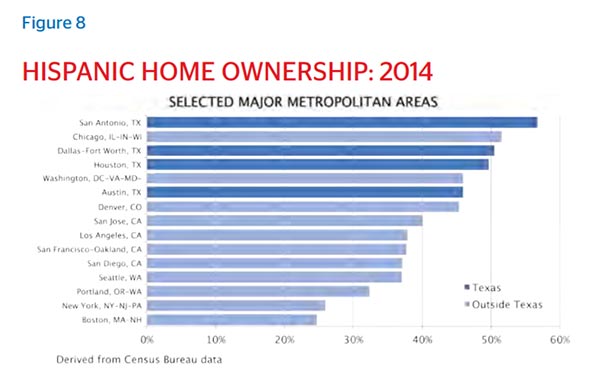

During that same time period the Latino population of Austin grew by 90 percent; Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston each grew by about 75 percent. In contrast, the Latino population in Los Angeles grew only 17 percent.

Houston now has a far higher percentage of foreign born residents than Chicago does. Dallas-Ft. Worth draws even with Chicago in that measurement, with an immigrant population that has grown three times as fast as that of the Windy City since 2000.

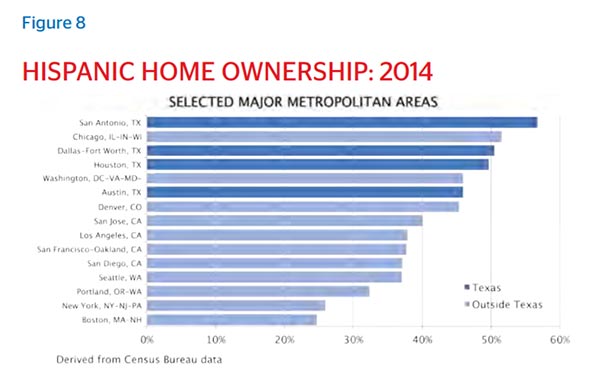

Economic opportunity explains much of the difference. Texas’ vibrant industrial and construction culture has provided many opportunities for Latino business owners. In a recent measurement of best cities for Latino entrepreneurs, Texas accounted for more than one third of the top 50 cities out of 150. In another measurement, San Antonio and Houston boasted far larger shares of Latino-owned businesses than Los Angeles, which also has a strong Latino presence.

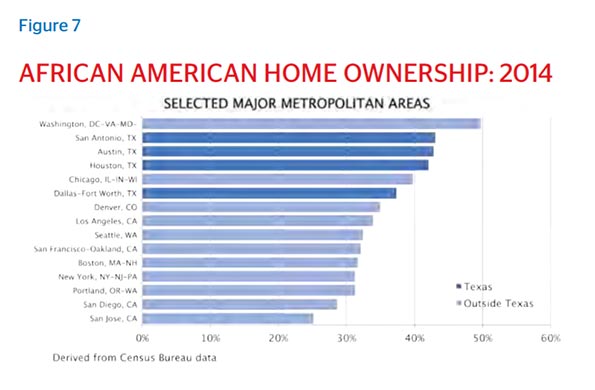

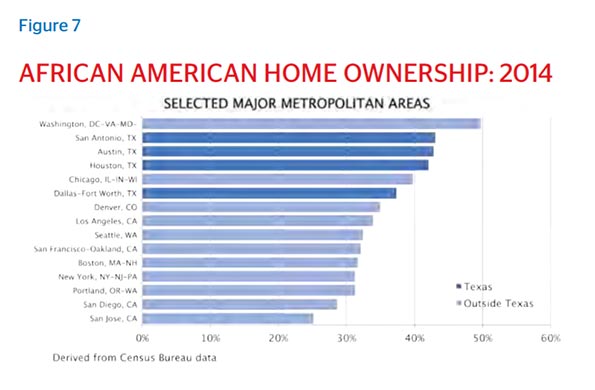

Texas is not a totally successful environment for minorities. Poverty levels for blacks and Hispanics remain high, and education levels lag in Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth and San Antonio. But the key factor is that Texas cities present superior prospects for upward mobility.

Domestic Migration Trends

Since 2000, Dallas-Ft. Worth has gained 570,000 net domestic migrants, and Houston has netted 500,000. In contrast, the New York area has had a net loss of over 2.6 million people, while Los Angeles hemorrhaged a net 1.6 million, and Chicago nearly 900,000. Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, Austin and San Antonio were all among the top eleven in total net domestic migration gains. The smaller Texas cities have also experienced large gains in migrants.

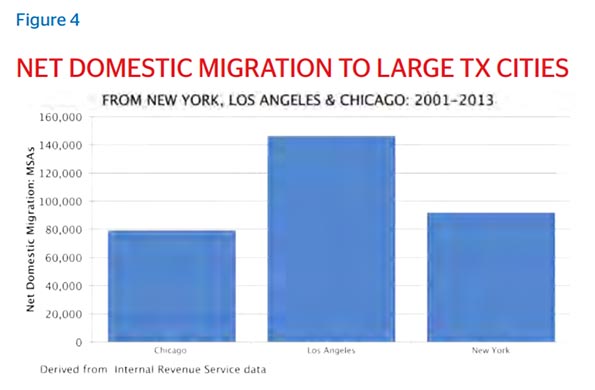

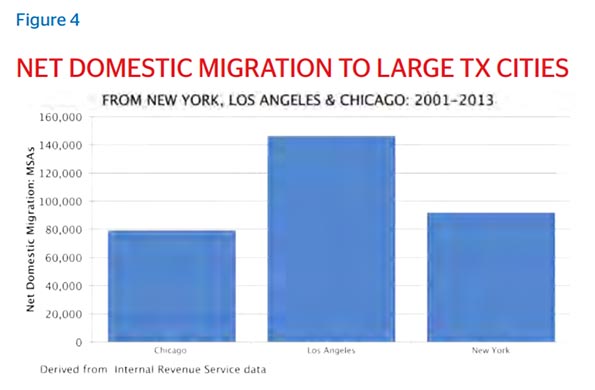

Many newcomers come from places — notably, California — where many Texans once migrated. Between 2001 and 2013, more than 145,000 people (net) have moved from greater Los Angeles to the Texas cities, while about 80,000 have come from Chicago and 90,000 from New York.

As Dallas Morning News columnist Mitchell Schnurman says, “If oil prices don’t go up, Texas can always count on California — and New York, Florida, Illinois and New Jersey.”

Creating the Next Generation of Urbanites

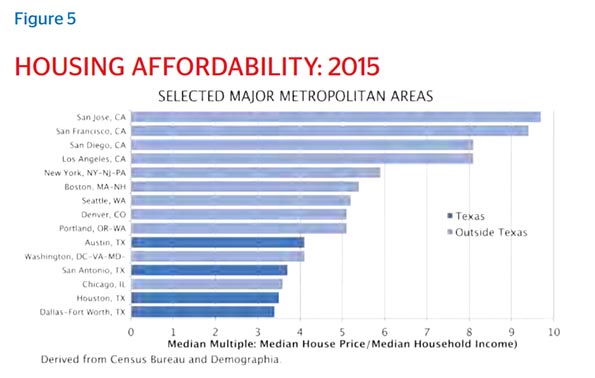

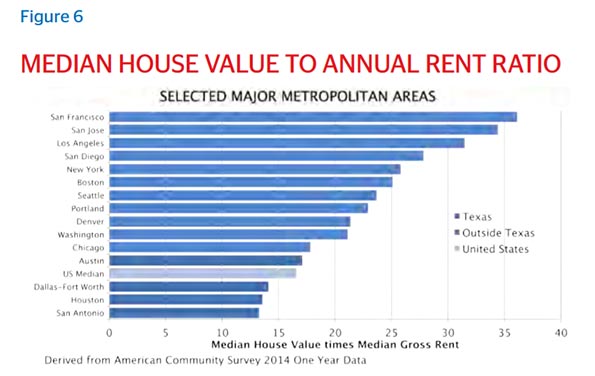

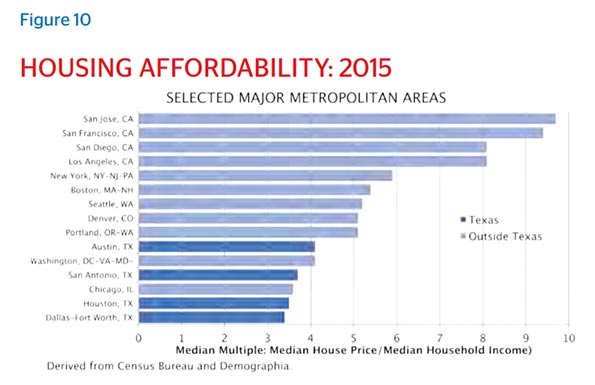

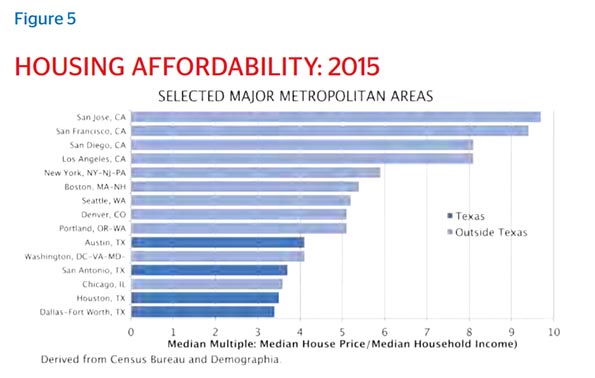

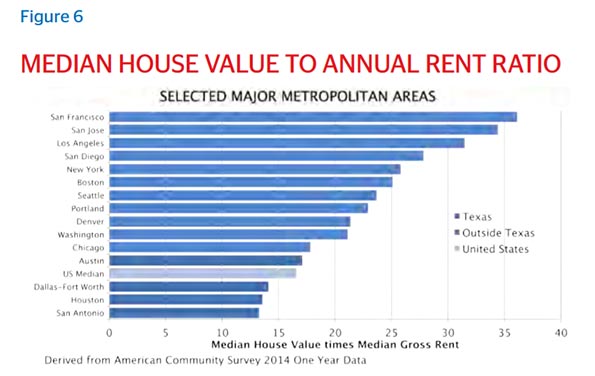

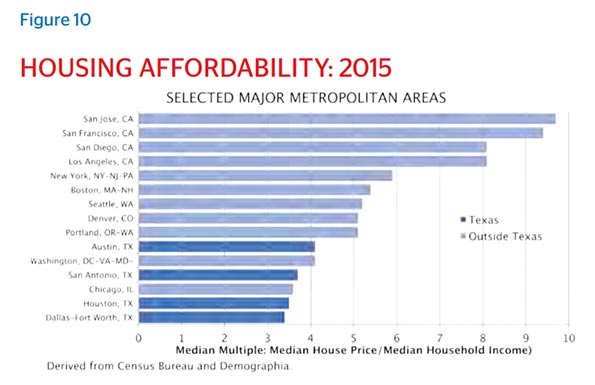

Texas urban growth has occurred more or less in conjunction with market demand, without the strict controls and grandiose ‘visions’ that dominate planning in New York and California. Overall housing prices in Texas cities remain, on average, one-half or less than those in coastal California cities such as San Francisco, San Jose, San Diego and Los Angeles. They are a third below those in New York, and have not experienced the huge spikes in housing inflation seen elsewhere in the Northeast Corridor, such as in Boston.

The lower house prices in Texas facilitate greater aspirations to home ownership, particularly among young people. The financial leap from renting to owning is far less daunting in Texas than it is the Northeast, or in some western US cities.

These lower prices have been a boon to ethnic minorities, who make up an ever-growing percentage of the population in cities nationwide. Latinos and African-Americans are far more likely to be home owners in Texas cities than in New York, Los Angeles, Boston or San Francisco.

A review of US Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis data indicates that housing costs are responsible for virtually all of the cost-of-living differences between the nation’s approximately 380 metropolitan areas. Consequently, it is far cheaper to live in Texas cities — even Austin — than in Boston, New York, Los Angeles, San Diego, Chicago and, most of all, the San Francisco and San Jose metropolitan areas.

Some observers lament that, due to market forces, the vast majority of Texas metropolitan growth — nearly 100 percent — has taken place in the suburbs and exurbs. Yet the Texas cities mirror nationwide experiences: there is essentially no difference between the share of metropolitan development in the Texas suburbs and the share in most other areas. The average share for all major metropolitan areas is 99.8 percent, including in Portland, Oregon, the much ballyhooed model for densification.

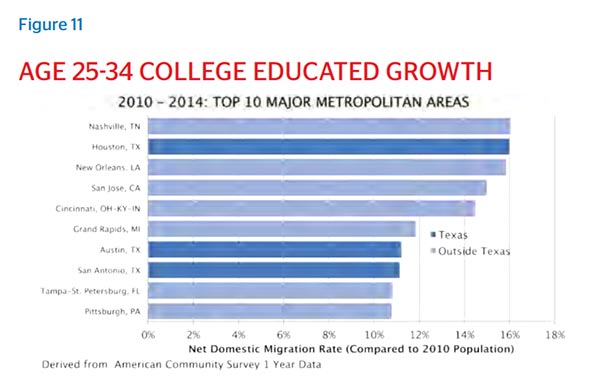

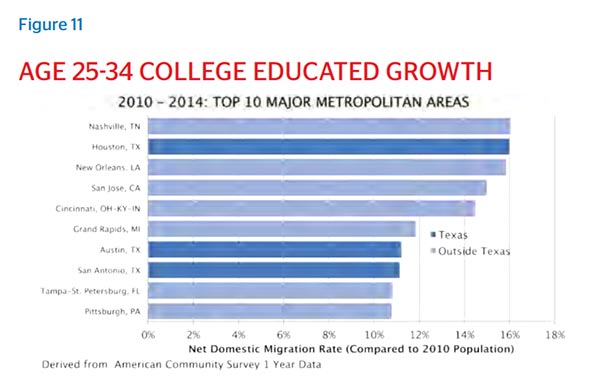

Ironically, dense housing development has grown more rapidly in Texas cities than it has in California, where the state has tried to mandate dense development. Building permit rates indicate that Texas cities have led the nation in both low density single family housing and in high density multifamily development. Between 2010 and 2015, Texas’ largest cities held three of the top five positions among the 53 major metropolitan areas in the issuance of multifamily building permits. Austin led the nation in these permits, while Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth had higher multifamily building permit rates than San Jose, Denver, Portland, Washington, or Los Angeles. At the same time, these three Texas cities also were in the top 10 in single-family building permits. Who occupies these new residences? Between 2010 and 2014 Texas cities, led by Austin and San Antonio, experienced higher rates of growth among college educated 25 to 34 year olds than did traditional ‘brain centers’ like New York, Boston, Chicago and even San Francisco. During the tech boom of the late 1990s, more people moved from Texas to the Bay Area than vice versa; in the current one, the pattern is reversed. A recent San Jose Mercury poll found that one-third of all Bay Area residents hope to leave the area, primarily citing high housing costs and overall cost of living.

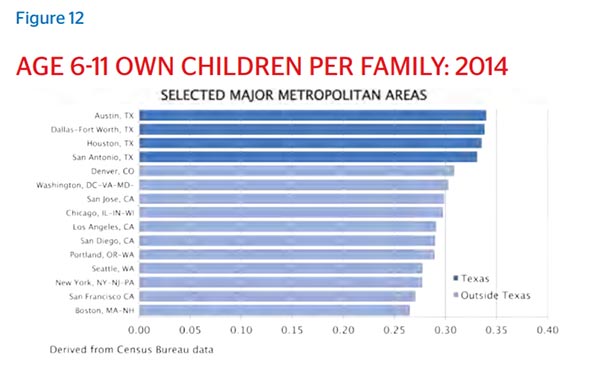

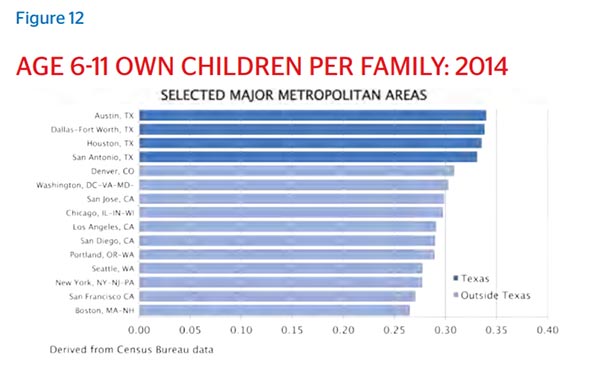

As young people mature, Texas’ major urban areas provide them with an array of choices. Texas city-dwellers, unlike many New Yorkers or San Franciscans, do not need to choose between living a middle class family lifestyle or staying in a city they love. Texas housing policies that allow organic growth driven by the market are attractive to young people seeking to establish careers or families, and to those who are already newly-established.

These trends will have a long-term demographic impact, and suggest a continuing Texan ascendency. According to the American Community Survey’s ranking of elementary-age school children per family, Austin, Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston and San Antonio rank in the top six among the 53 major metropolitan areas. By comparison, Chicago ranks twenty-second, Los Angeles twenty-seventh, New York thirty-sixth, and San Francisco 45th.

The Lone Star State is already home to two of the nation’s five largest metropolitan areas, the first time in history that any state has so dominated the nation’s large urban centers. At its current rate of growth, Dallas-Ft.Worth, could surpass Chicago in the 2040s, as would Houston a decade later. By 2050 the Lone Star state could dominate America’s big urban centers even more than it does now.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, will be published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

“Welcome To Texas” flickr photo by David Herrera is licensed under CC BY 2.0