Whatever President Obama proposes in his State of the Union for the economy, it is likely to fall victim to the predictable Washington gridlock. But a far more significant economic policy debate in America is taking place among the states, and the likely outcome may determine the country’s course in the post-Obama era.

On one side are the blue states, who believe that higher taxes are not only just, but also the road to stronger economic growth. This is somewhat ironic, since, as we pointed out earlier, higher taxes on the “rich” would seem to hurt their economies more, given their high concentration of high-income earners. However, showing themselves to be gluttons for punishment, many of these states have decided to double down on high taxes, raising their rates to unprecedented levels.

This cascade of higher income taxes started in 2011 when Illinois, arguably the big state with the weakest economy, and the lowest bond ratings, raised income taxes by 66% and business taxes by 46%. Over the past year several other Democratic state governments have pushed through income tax increases, notably California, which raised the tax rate on people with annual income over $1 million to 13.3%, the highest in the nation. And now it appears that Massachusetts and Minnesota are about to raise their taxes as well.

This is happening at the same time that some red states — notably Kansas and Louisiana — are looking at lowering income tax rates by shifting to rely more on consumption or sales tax revenues. Some red states don’t have income taxes — notably Florida, Texas and Tennessee — and most of those who do are holding the line. Red state leaders, most notably Louisiana’s Bobby Jindal, are placing their bets on expanding their economies, which would create new taxpayers, boost consumer spending and expand collections of sales taxes.

The contrast with the blue states — not so much those who voted for Obama, but those controlled totally by Democrats — could not be clearer. They appear to have chosen an economic path that essentially penalizes their own middle and upper-middle class residents, believing that keeping up public spending, including on public employee pensions, represents the best way to boost their economy.

Yet the gambit of raising state income taxes could not be coming at a worse time. The president’s adopted tax reforms have eliminated write-offs for state taxes for those individuals with incomes over $250,000 and families earning over $300,000. As a result, the affluent residents of these states — California, New York, New Jersey and Illinois alone count for 40% of these deductions nationally — now can expect to get whacked coming and going.

So which strategy is likely to work best? Most conservatives would assert that the red state approach will prove more effective. But in the short run at least, the free-money policies of the Federal Reserve are supporting many blue-state economies. Plastering institutional investors with low-interest greenbacks raises the price of assets — notably stocks and real estate — creating high incomes for wealthy taxpayers that can then fill the coffers of these states.

This particularly benefits New York, which depends heavily on Wall Street earnings. (Residents of New York City, which has a city-level income tax on top of high state rates, have the highest overall tax burden in the country.) States such as Massachusetts, Minnesota and even Illinois also have larger than average pockets of wealthy investors; if they do well, higher income taxes could, in the short run at least, bring substantial returns to their state coffers.

Perhaps the most obvious short-term beneficiary of the new high-tax policy may be my adopted home state of California. Given the higher share of the tax burden borne by the wealthy, a rising stock market tends to send gushers of funds into state coffers, particularly when Silicon Valley is enjoying one of its periodic bubbles. Equally important, increases in real estate prices — up some 25% in Orange County alone — also drives up capital gains and income taxes. This growth is driven not by higher salaries for Californians but is largely investor driven. A remarkable one in three California home purchasers paid with cash in 2012, up from 27% from the previous year. Home prices are climbing rapidly in the Bay Area, where the economy is performing better, and could reach 2007 pre-crash levels within the next year or two, if the current tech bubble continues.

In the short run, asset inflation combined with higher levels of taxation could solve California’s perennial budget problems, at least temporarily. The state is expected to move into surplus over the coming year. Gov. Jerry Brown sees this convergence as justification for his current “victory lap” in the state and national media. Brown, argues progressive analysts such as Harold Meyerson, has become very much the model of a modern blue state leader.

Yet, in the longer run, it’s dubious that higher income taxes will make states like California any more competitive or stable fiscally. During the property bubble in the mid-2000s, California also balanced the budget; in 2007 Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger started comparing the Golden State to ancient Athens and blithely initiated draconian laws on climate change as well as expansion of the social safety net. All things seemed possible until the bubble burst, and with it the windfall from a relative handful of taxpayers. As revenues fell, the state went through five years of huge deficits, a major loss of jobs and growing impoverishment.

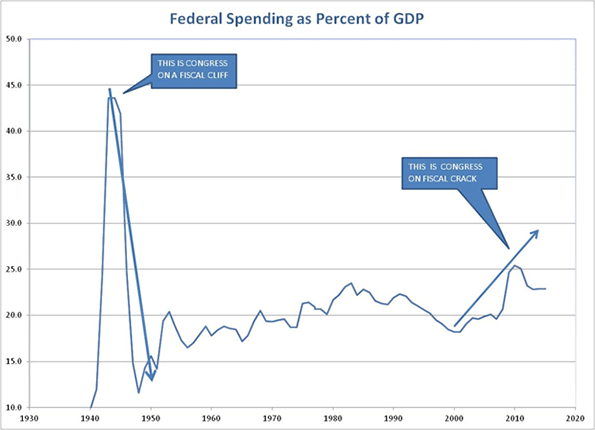

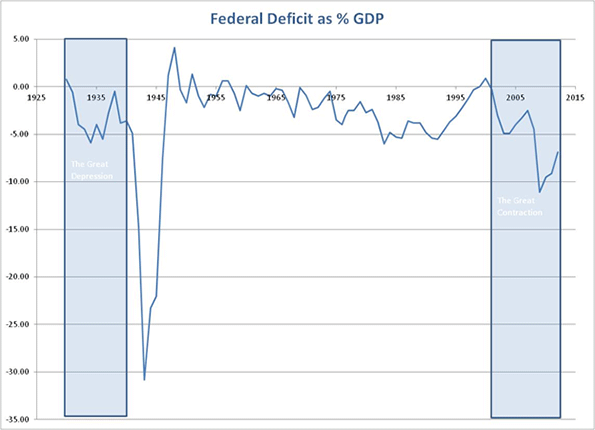

This is likely to happen again, once there’s a downturn in the housing or stock markets. In a sense higher income taxes serve as an equivalent to what economist Suzanne Trimbath calls “fiscal crack.” For a short period there’s euphoria, as tax revenues flow in and the economy seems to recover. Yet the real problems, such as inadequate private-sector job growth, are never addressed, and as the high fades, the state again faces a loss of jobs and people.

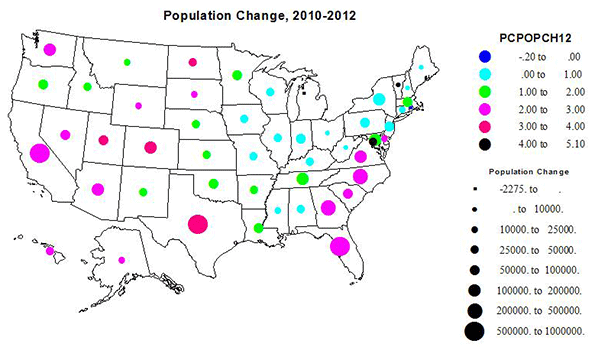

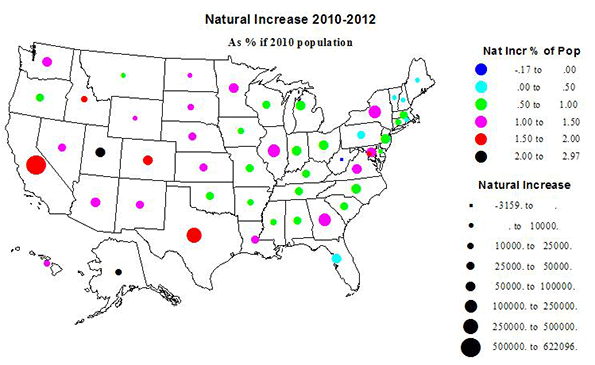

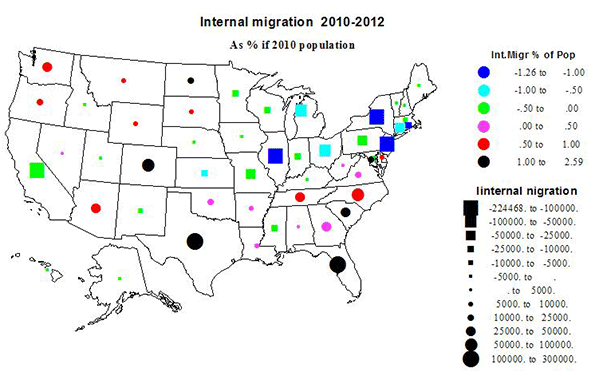

Perhaps most troubling, states with high income taxes tend to lose people, particularly in the middle class. Over the past 20 years the four biggest net losers of population were high tax states: California, New York, New Jersey and Illinois. Between them they lost roughly a net 8 million out-migrants. The two big net winners, Texas and Florida, had no such taxes, and most of the other big gainers were relatively low-tax states.

Of course, not everyone is so concerned with income taxes. The ultra-wealthy like David Geffen seem gleeful to pay higher taxes, perhaps because this class, as Mitt Romney showed, have lots of ways to reduce their tax burdens, and after all, don’t have to worry about personal cash flow to keep the business going.

But enthusiasm for higher taxes historically has been less marked among the much larger group who, although affluent, are far from billionaires. Between 2006 and 2009, California lost a net 45,000 taxpayers earning between $5 million and $300,000 a year, according to the State Department of Finance.

To be sure, the outward movement slowed during the recession, but more recently the pattern has reasserted itself. Last year, all ten of the leading states gaining domestic migrants were low-tax states including five with no income tax: Texas, Florida, Tennessee, Washington and Nevada. In contrast high-tax New Jersey, New York, Illinois and California suffered the highest rates of out-migration.

Given these realities, raising already high income taxes has to qualify as somewhat self-destructive over the long run. But so great are the pressures in the blue states to fund expansive welfare programs and public employee pensions that there’s little chance the rising tax tide will soon abate. Sadly, there’s no hotline that seems capable of persuading them to rethink their latest suicidal lurch.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register . He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Income tax photo by Bigstock.