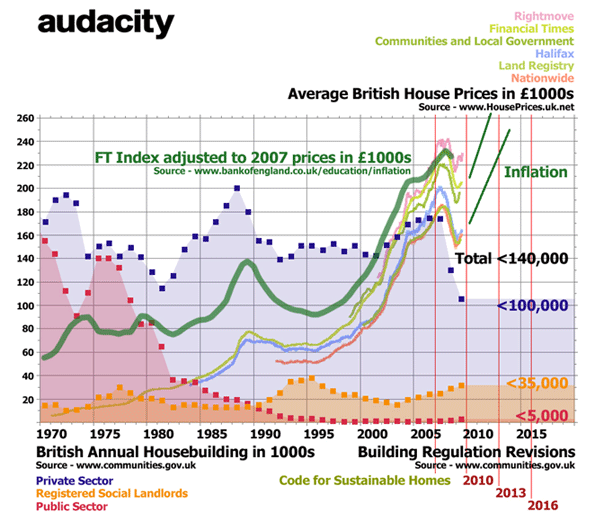

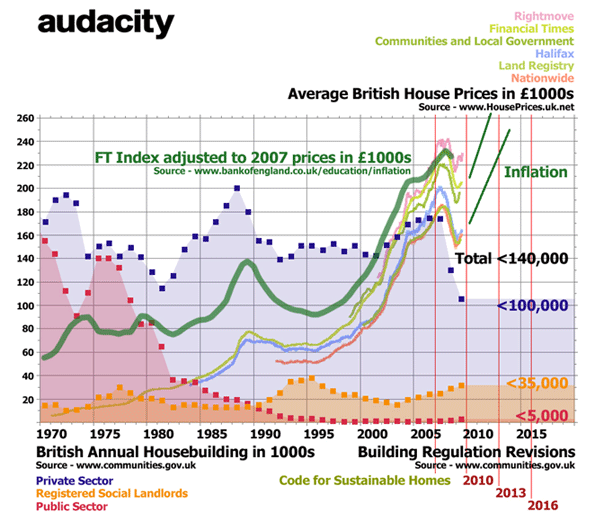

British house construction has remained at a low level for a decade. Total new house and flat completions for all tenures last year were 113,670 for England, 17,470 for Scotland, and 6,170 for Wales. Excluding Northern Ireland that is 137,310 for Britain. Under 140,000 homes a year is low for a nation of 60 million.

We are nearly at the lowest level of housing production since reliable records began in the 1920s. (Note 1)

Anyone expecting British house building to pick up soon will be disappointed, even as the housing market inflates into another bubble. Grant Shapps, the Coalition government’s Housing and Local Government Minister, is also hoping that house price inflation will not return to make the present housing predicament worse.

He will be disappointed, too. Shapps wants modest deflation and more houses to be built. However, he is powerless to make that happen while his government sustains the national denial of Freehold development rights that in Britain defines the planning system. By denying landowners the right to build on any land they own, the system works against significant levels of housing production.

The renewal of house price inflation

The low level of production all but guarantees renewed house price inflation. According to estate agency Savills, inflation-adjusted house prices grew by 68 per cent in the decade up to 2010, even after the British housing market finished wobbling during the sub-prime mortgage finance crisis. Savills told readers of The Telegraph that house prices will inflate by 40 per cent in real terms over the next decade.

Britain’s vast majority of home owners will be relieved. Most people have felt uneasy with financial dependency on the debt and equity in their home. For most British households wages and pensions are insufficient.

At the root of the problem lies the peculiar nature of Freehold in Britain. The government enjoys an effective national instrument in their effort to protect the housing market. An old innovation of the post-war planning system, this ensures cheap farm land can never come onto the market to allow the building of low cost homes in great volume, sufficient to precipitate a housing market crash worth having. Planning as a denial of development rights works very well to protect the members of the Council of Mortgage Lenders.

This keeps house building volume low. Britain’s former volume house builders have begun to make the painful adjustment to work within the Coalition’s planning system. It will not be easy for them.

The national denial of development rights is sustained, and in many ways the problem is worse under the Conservative-led coalition than under New Labour.

The house builders have been stripped of New Labour’s national target of 240,000 net additional homes a year, but that was an unmet and inadequate target. Even more troubled are plans to develop 50 proposed “eco towns” also proposed by Labour, itself a small, even deluded, enterprise that is pathetic compared to development elsewhere in the world.

Urban expansion and new settlements – whether in Britain or elsewhere – require land. And Britain, contrary to popular belief has land aplenty. The restraints placed on builders can best to described in the words of Sir Peter Hall, as a “Land Fetish”.

The planning system also is host to an eco-fetish that the Coalition appears willing to sustain regardless of housing need.

Inevitably some house builders will have subscribed to the idea that the environment is too precious to allow much land to be developed, but not all. This leaves no centralised attempt to satisfy the demand for new household formation following from population growth, the needs of immigrants, or to encourage the replacement of the worst housing stock. For greens of the more misanthropic persuasion, opposition to both population and production makes sense. They don’t want humanity to reproduce either biologically or industrially. They don’t want a world that is always about advancing human interests through industry.

Yet the need for new homes won’t so easily go away.

A three sided predicament

This contemporary British housing trilemma will not be easily resolved. The country seems to accept expensive, inadequate housing and mortgage debt as a fact of life.

Yet this leaves us with no solution for future needs.

Something needs to change. Hugh Pavletich and Wendell Cox publish as Demographia have found – for the seventh year running – increasing unaffordability of British housing.

The Solution: 250 New Towns

The only reasonable solution is to tear down the current planning structure. What we need is an audacious move to build some 250 new towns.

This movement would try to replicate past successes. In the brief inter-war period, 1918 to 1938, popular owner occupation flourished, with economically struggling farmers keen to sell their Freehold land to house builders.

How long will Britain live with low levels of construction, increasingly higher prices and consistently low levels of affordability? The increasing drag of house price inflation on household incomes and the acceptance of poor quality British housing in short supply cannot be sustained indefinitely.

How long will Britain sustain housing unaffordability as a financial opportunity, protected by a weak government?

The British collective obsession with inflating house prices must end sometime, unless we are to lose all sense of housing primarily as somewhere useful to live.

The freedom to build on your own land will deflate the housing market, dramatically in some locations. Giving all landowners their Freehold right to build will liberate the commercial construction industry from the burden of inflated land prices, allowing disruptive advances in industrial production.

If Britain faces the house price inflation projected by Savills in the next 10 years there are many home owners dependent on housing equity who will not object. Neither will the house builders object too much as they build a low number of luxury eco-homes, to the undoubted applause of the architectural press. They may enjoy the praise for their greenness. Farmers might subsist as environmentalists. Greens will be sufficiently deluded to imagine there was some point to all this. The City will make a healthy return.

The green zealots are conspicuous, and need to be confronted by industrialists with a sense of humanity. Now is no time to let them get away with their anti-humanism.

Britain certainly is capable of more than is currently being discussed. National housing output had peaked in 1968 at 413,714, more than twice the current rate.

We have to answer the question: Who will organise to better explain and end the housing predicament in low wage industrial Britain? We are hoping the 250 new towns club can start the ball rolling.

—-

Note 1 – Marian Bowley, ‘Table 2, Numbers of Houses Built in England and Wales between January 1, 1919 and March 31, 1939’, in Housing and the State 1919-1944, London, George Allen & Unwin, 1945, p 271

Ian Abley, Project Manager for audacity, an experienced site Architect, and a Research Engineer at the Centre for Innovative and Collaborative Engineering, Loughborough University. He is co-author of Why is construction so backward? (2004) and co-editor of Manmade Modular Megastructures

(2004) and co-editor of Manmade Modular Megastructures . (2006) He is planning 250 new British towns.

. (2006) He is planning 250 new British towns.