In 1949 the historian Carey McWilliams defined California as the “the Great Exception” — a place so different from the rest of America as to seem almost a separate country. In the ensuing half-century, the Golden State became not so much exceptional but predictive of the rest of the nation: California’s approaches to public education, the environment, politics, community-building and lifestyle often became national standards, and even normative.

Today California is returning to its outlier roots, defying many of the political trends that define most of the country. Rather than adjust to changing conditions, the state seems determined to go it alone as a bastion of progressivism. Some Californians, going farther out on a limb, have proposed separating from the rest of the country entirely; a ballot measure on that proposition has been proposed for 2018.

This shift to outpost of modern-day progressivism has been developing for years but was markedly evident in November. As the rest of America trended to the right, electing Republicans at the congressional and local levels in impressive numbers, California has moved farther left, accounting for virtually all of the net popular vote margin for Hillary Clinton. Today the GOP is all but non-existent in the most populated parts of the state, and the legislature has a supermajority of Democrats in both houses. In many cases, including last year’s Senate race, no Republicans even got on the November ballot.

Homage to Ecotopia

The election of Donald Trump has expanded the widening gap. The two biggest points of contention going forward are likely to be climate change, which has come to dominate California’s policy agenda, and immigration, a critical issue to the rising Latino political class, Silicon Valley and the state’s entrenched progressive activists.

Most of the big cities — Los Angeles, San Jose, San Francisco, Oakland and Sacramento — have proclaimed themselves “sanctuary cities,” and the state legislative leadership is now preparing a measure that would create “a wall of justice” against Trump’s agenda. If federal agents begin swooping down on any of the state’s estimated 2 million undocumented immigrants, incoming Attorney General (and former congressman) Xavier Becerra has made it among his first priorities to “resist” any deportation orders, including paying legal fees.

Equally contentious will be a concerted attempt to block Trump’s overturning of President Obama’s climate change agenda. In recent years Gov. Jerry Brown has gone full “Moonbeam,” imposing ever more stringent environmental policies on state businesses and residents. The most recent legislation signed by Brown would boost California’s carbon reductions far beyond those agreed to by the U.S. in the Paris accord (which Trump has said he will withdraw from). All of this is being done along with a virtual banning of nuclear power, which, as the Breakthrough Institute’s Michael Shellenberger notes, remains the largest and most proven source of clean energy.

California’s draconian climate policies have been oft-cited by Obama and environmentalists as a role model for not only America but the world. However, they will not be widely emulated in the rest of the country during the next four years. Instead, California may be opting for a kind of virtual secession, following the narrative portrayed in Ernest Callenbach’s 1975 novel, “Ecotopia,” where Northern California secedes from the union to create a more ecologically perfect state.

Ironically, the state’s policies, which place strong controls on development, road construction, and energy production and usage, are somewhat symbolic; by dint largely of its mild climate, the state is already far more energy efficient than the rest of the country. But to achieve its ambitious new goals, most serious observers suggest, the state would lose at least 100,000 jobs and further boost energy prices — which disproportionately affect the poorer residents who predominate in the state’s beleaguered, and less temperate, interior.

The impact of these policies would be far-reaching. They have already reduced outside investment in manufacturing to minuscule levels and could cost California households an average of $3,000 annually. Such economic realities no longer influence many California policymakers but they could prove a boon to other states, notably Texas, Arizona and Nevada, which make a sport of hunting down California employers.

A ‘Light Unto the Nations’?

Even with these problems, no other part of the country comes close to being as deeply progressive as California. Illinois, President Obama’s home state, is a model for nothing so much as larceny and corruption. New York, the traditional bailiwick of the progressive over-class, is similarly too corrupt and also too tied to, and dependent upon, Wall Street. In addition, both of these states are losing population, while California, although slowing down and experiencing out-migration by residents to other states, continues to grow, the product of children born to those who arrived over the past three decades.

California’s recent economic success seemingly makes it a compelling “alt-America.” After a severe decline in the Great Recession, the economy has roared back, and since 2010 has outpaced the national average. But if you go back to 2000, metro areas such as Austin, Dallas, Houston, Orlando, Salt Lake City and Phoenix — all in lower-tax, regulation-light states — have expanded their employment by twice or more than that in Los Angeles.

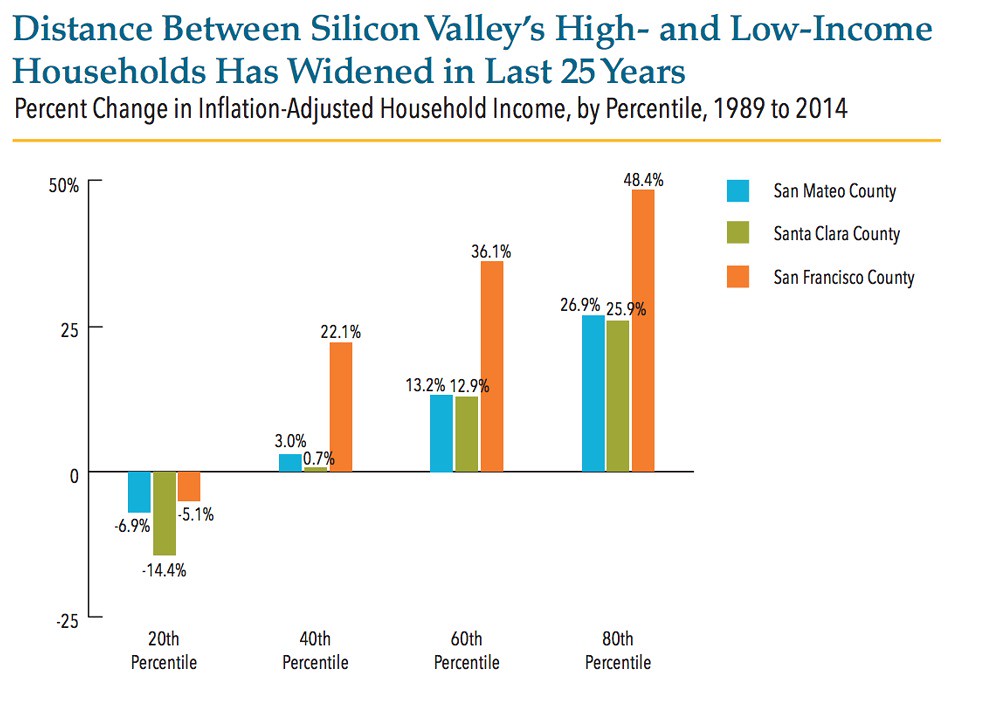

Indeed, a closer examination shows that the California “boom” is really about one region, the tech-rich San Francisco Bay Area, with roughly half the state’s job growth recorded there since 2007 even though the region accounts for barely a fifth of the state’s population. Outside the Bay Area, the vast majority of employment gains have been in low-paying retail, hospitality and medical fields. And even in Silicon Valley itself, a large portion of the population, notably Latinos, are downwardly mobile given the loss of manufacturing jobs.

According to the most recent Social Science Research Council report, the state overall suffers the greatest levels of income inequality in the nation; the Public Policy Institute places the gap well over 10 percent higher than the national average. And though California may be home to some of the wealthiest communities in the nation, accounting for 15 of the 20 wealthiest, its poverty rate, adjusted for cost, is also the highest in the nation. Indeed, a recent United Way study found that half of all California Latinos, and some 40 percent of African-Americans, have incomes below the cost of necessities (the “Real Cost Measure”). Among non-citizens, 60 percent of households have incomes below the Real Cost Measure, a figure that stretches to 80 percent below among Latinos.

In sharp contrast to the 1960s California governed by Jerry Brown’s great father, Pat, upward mobility is not particularly promising for the state’s majority Latino next generation. Not only are housing prices out of reach for all but a few, but the state’s public education system ranks 40th in the nation, behind New York, Texas and South Carolina. If California remains the technological leader, it is also becoming the harbinger of something else — a kind of feudal society divided by a rich elite and a larger poverty class, while the middle class either struggles or leaves town.

Will America Turn to the California Model?

The new California model depends largely on one thing: the profits of the very rich. Nearly 70 percent of the state budget comes from income tax, half of which is paid by the 1 percent wealthiest residents (the top 10 percent of earners accounted for nearly 80 percent). This makes the state a model of fiscal instability. As long as the Silicon Valley oligarchs and the real estate speculators do well, California can tap their wealth to pay its massive pension debt, and expand the welfare state inexorably for its increasingly redundant working-class population.

It’s highly dubious this model would work for the rest of the country. Due largely to its concentration of venture capital, roughly half the nation’s total, Silicon Valley may be able to continue to dominate whatever is the “next big thing,” at least in the early stages. Even parts of the tech community, such as Uber, Lyft and Apple, have announced major expansions outside of the state, in some cases directly due to regulatory restraints in California. Layoffs, meanwhile, are rising in the Valley as companies merge or move to other places. Google, Facebook and others, of course, will remain, keeping the big money in California, but the jobs could be drifting away.

Under any circumstances, the rest of the country — with the exception of a few markets such as Manhattan and downtown Chicago — could not absorb the costs for housing or the taxes California imposes on its residents and businesses. Part of the reason stems from the fact that California is indeed different; its climate, topography, cultural life cannot be easily duplicated in Kansas City, Dallas or anywhere else. People will pay for the privilege of living in California, particularly along the coast. Would they do so to live in Minneapolis or Charlotte?

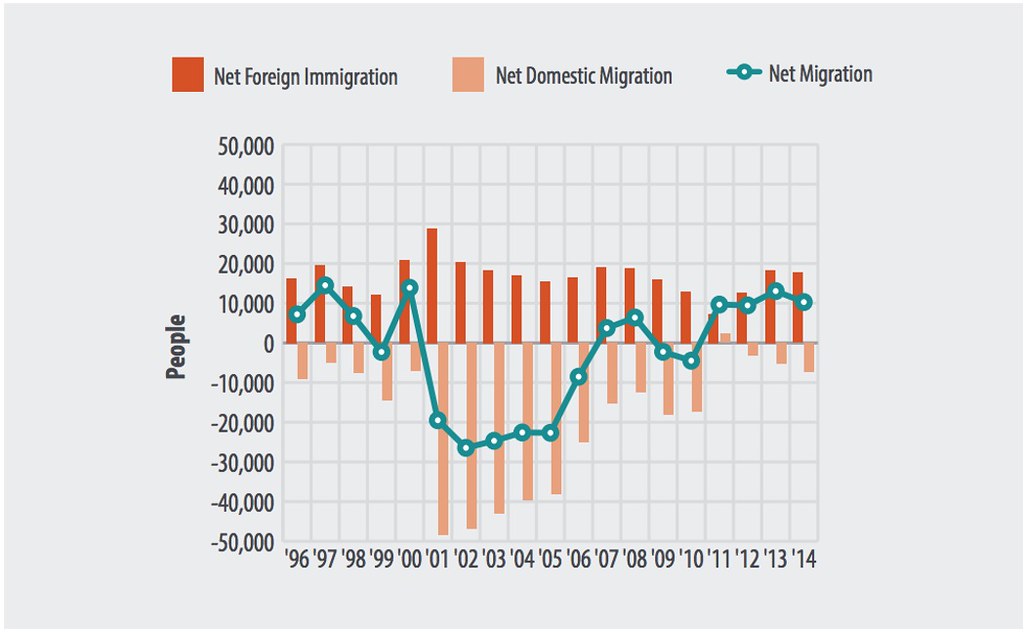

Nor, unlike during much of the postwar era, can it be said that California represents the demographic future. The state — even the Bay Area — generally loses people to other states, particularly those in middle age, according to an analysis of IRS numbers. Brown apologists suggest it’s only the poor and uneducated who are leaving, but it also turns out that California is losing affluent people just as rapidly, with the largest net loss occurring among those making between $100,000 and 200,000.

Perhaps more revealing, the number of children is declining, particularly in the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas. Children made up a third of California’s population in 1970, but USC demographer Dowell Myers projects that by 2030 they will compose just a fifth.

Nor is help on the way. Although boomtown San Francisco has maintained its share of millennials, most large California cities have not. And the number of people in their mid-thirties — prime child-bearing years — appears to be declining rapidly, notably in the Bay Area. Coastal California is becoming the golden land for affluent baby boomers rather than young hipsters. Surfing dudes will increasingly be those with gray ponytails.

Instead of a role model for the future, the Golden State seems likely to become a cross between Hawaii and Tijuana, a land for the aging rich and their servants. It still remains a perfect social model for a progressive political regime, but perhaps not one the rest of the country would likely wish to, or afford, to adopt.

This piece originally appeared in Real Clear Politics.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, was published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo by Thomas Pintaric (Own work) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons