The common line used by advocates of housing affordability has been that the solution lies in “free markets”. Yet this “free market” solution does not address the fundamental problem which is really a political one.

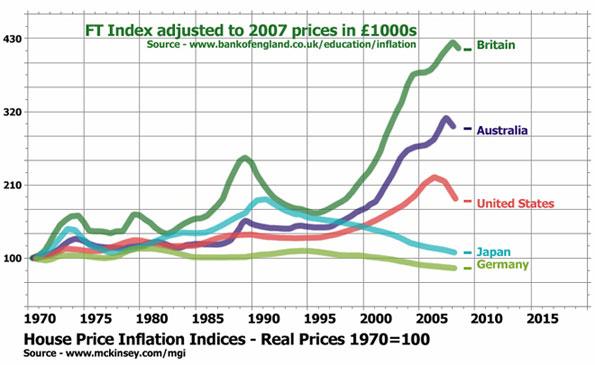

This true fundamental problem is particularly evident here in Britain, the leader in house price inflation and housing financial bubbles since the 1970s. In their recent report Global capital markets, the McKinsey Global Institute has confirmed what has been shown in recent Demographia surveys.

The root of this problem lies with an elite agenda that is highly ideological. The ideology at work is environmentalism, making a moral virtue of the retreat of political and commercial elites from the industrial production of housing.

The preference is for interest payments on a fund of mortgage debt rather than the effort of turning a profit from development, let alone construction. Professionals like estate agents, planners, architects, and bankers are certainly in collusion with that elite ideology.

That is not to say there is a conspiracy to plan a housing bubble. That is too crude. There is clearly regulation and legislation. On 24 November 2009 the Housing Minister John Healey confirmed that Britain will be the first country in the world to require zero carbon homes as a matter of law from 2016. Britain is the world leader in green ideology.

John Healey

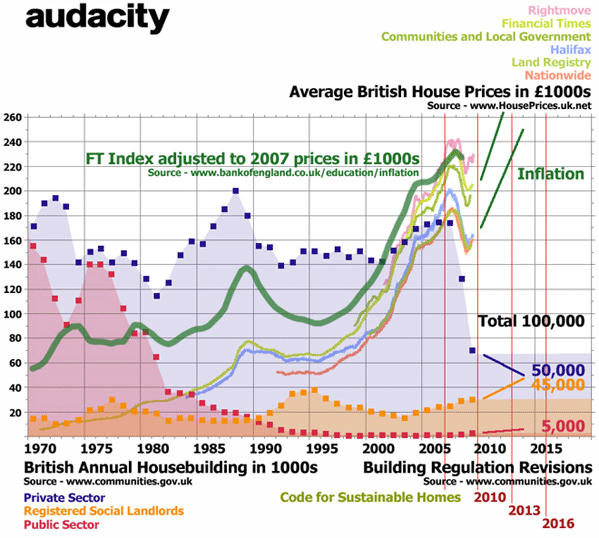

All of the newly built British housing will have much better insulated walls, windows, roofs and floors. The clear aim of the government is to keep reducing the energy consumption of all new homes to be measured in kilowatt-hours per square metre of floor area per year. New Labour hope to make it law that total energy consumption is no more than 46 kWh/m2/year for semi-detached and detached homes, and then no more than 39 kWh/m2/year for all other homes. The energy efficiency standards will be applied from 2016, subject to yet another consultation on the Code for Sustainable Homes, announced at the end of 2006, and technically published for use on a voluntary basis in 2007. The building regulations get revised in 2010, 2013, and 2016 leading to this legal requirement for maximum energy consumption in all new homes.

Healey says that “zero carbon” is a concept that will apply to a new home at the “point of build”. ‘We are not going to regulate through this policy how occupants live in them,’ he says. However the Code for Sustainable Homes assumes patterns of behaviour. Environmentalists within and without government will argue that behaviour needs to change. They will be suggesting all sorts of intrusions into daily life.

British environmentalism couldn’t be more ideological, and more of a barrier to the production of affordable housing. The planning system has been “greened”. The mood is against development, and planning approvals for new land for new housing are hard to obtain. The zero carbon requirement will only apply to around the 100,000 new homes that will be built annually, while the existing stock is around 26 million homes. Healey is also going to regulate existing housing, and is not just looking at the residential sector.

I am sure politicians like Healey don’t want their pursuit of “zero carbon” buildings to mean that fewer buildings are built. I am sure there are some environmentalists who will be pleased that building activity is in decline. The logic of green thinking entails that the most energy efficient thing to do is not to build more buildings at all.

It is green not to build new homes to meet demographic demand. Let people modify their behaviour, say the environmentalists, and live together in as much of the existing stock as can be refurbished. It also happens that the existing stock is highly mortgaged, and the vast majority doesn’t want their homes to fall in value. An indefinite policy of green refurbishment of the homes that already exist and a future of house price inflation are highly compatible. That suits the mortgage lenders and the government. The commitment to “zero carbon” allows government to appear virtuous in its legislation for the new build sector.

This suits the financial markets as well, since it guarantees house price inflation by making it difficult to meet the demographic demand for homes. Environmentalism offers more and more reasons not to build. Green thinking ensures that house price inflation can be sustained through a bubble, and projected beyond the bursting of that period of financialisation into the next.

As capitalism ”greens” itself, capitalists continue to profit, while not meeting the fundamental demands of the people for housing. But simply restoring “the free market” will not solve the problem. In an old industrial country like Britain, there are ever more people who don’t earn enough to buy a home even at the “affordable” price of two and a half times their gross annual household income, which is the Demographia measure of affordability.

This reality has a great appeal to what Robert Bruegmann refers to as “the incumbents club” – established homeowners, increasingly older, and those with inherited money. That majority want homes to be an appreciating asset, not a depreciating utility, like a pair of trousers, or a car. They want their home to appreciate in value, and they want to be green. Most people want to be greener and better off.

Being anti-development for green reasons allows the incumbents to preserve their wealth, while making mundane opposition to new house building, or the attempt to constrain “sprawl”, seem virtuous. People don’t wake up thinking that they will inflate the value of their home by resisting sprawl in principle. Instead they oppose new development in the mistaken belief that Climate Change is caused by sprawling development. It is common for people to think that sprawl is bad for the planet, even while living, mostly with a mistaken sense of guilt, in the sprawl.

By hoping for a “free market” solution to the problem of unaffordability, Hugh Pavletich of Demographia assumes that it is politicians, businessmen, and professionals who have distorted the market for reasons of narrow and immediate self-interest. Yet that is not how people think: they believe their environmentalism is morally above self-interest. They are saving the planet in their minds by blocking new building, and by their opposition to sprawl. The incumbents’ club members can feel virtuous at little cost to themselves and don’t worry too much about house price inflation. Of course there is no actual Club. There is no conspiracy. Homeowners simply share a self-interest in raising the value of their home, and tend to also want to show how selflessly green they are.

This all has had the effect of making the lending of mortgages on inflated land values a much larger business than the construction of homes. No-one planned to cause a sequence of bubbles, but Britain’s desperate social dependence on sustained house price inflation can’t be brought to an end easily.

The only way to stop national or regional housing bubbles recurring is the establishment of the freedom for everyone to build a home on cheap agricultural land without any government or professional hindrance except in matters of technical building regulations. Fire should not spread, and buildings should not fall down. But even building regulations can become ideological rather than technical. The British building regulations, as Healey has made clear, will also push energy efficiency standards to illogical extremes of peak performance in an attempt to address Climate Change. Even while the supply of new homes reduces

The political freedom to build wouldn’t be a “free market” because not everyone is able to raise the finance to buy cheap land and pay for construction. The idea of a “free market” is a long running ideological myth. But the universal freedom to build would mean people are free to attempt to raise the finance to buy land and build.

More importantly, the freedom to build would undermine the financialisation of the housing market. If everyone was free to build on cheap land the incumbents’ club would have to compare the value of their existing home to the cost of building a new one. Mortgage lenders would not be able to lend over the cost of construction unless they felt secure in doing so. The security of the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act would be removed for financiers. Government, the finance system, planners, or the incumbents’ club will be ideologically opposed to that for a host of environmental reasons. Britains mostly want to be greener but with renewed house price inflation, while no-one wants to make an argument explicitly for un-affordability. This may be confused and deluded, but it is an ideology promoted by the British government.

However, ideas can be challenged and changed. One step is to understand that there is no “free market” housing solution. Getting rid of the 1947 denial of the freedom to build doesn’t mean an end to planning. Homes will still need to be planned, just as they were before 1947. But planners will not have the power to stop people from building. There is a need to politically end the environmentalist denial of the freedom to build in an industrial democracy. With a population free to build the finance system would be more interested in cheapening new construction on lower cost land, and not preoccupied with securing the financialisation of periodic but persistent house price inflation. A freedom to build is very much not a right to a home. It is a freedom from the obstructions of planners, with the weight of government legislation behind them. A freedom that is denied to protect the environment, a denial that sustains house price inflation.

The market is not capable of being a “free market”. Capitalism is a system of control by political and commercial elites, and their professional employees. British capitalists tend to be less interested in industry, which is held to have caused Climate Change, and more interested in finance these days. What is precisely missing in the face of the morally selfless capitalist ideology of environmentalism is an ideology in favour of raising the productive capacity of the construction industry based on a universal sense of immediate and material self-interest. Getting rid of the 1947 planning legislation is a limited attempt to reconnect house building with the cost of construction and household incomes by removing the means by which house price inflation is sustained. Homes would be more of a utility than an investment in Britain, and we would cease to be world leaders in housing based financial bubbles.

To do that requires us to oppose those who would be world leaders in the environmental ideology that industrial production is a problem for the planet. In Britain we need to set people free to build housing to the best of their abilities within a capitalist planning system stripped of the legal powers it gained in 1947. Innovative in their day, British planning now only sustains housing bubbles and restricts people’s opportunity for decent housing.

Ian Abley, Project Manager for audacity, an experienced site Architect, and a Research Engineer at the Centre for Innovative and Collaborative Engineering, Loughborough University. He is co-author of Why is construction so backward? (2004) and co-editor of Manmade Modular Megastructures

. (2006) He is planning 250 new British towns.