INTRODUCTION

During the first ten days of October 2008, the Dow Jones dropped 2399.47 points, losing 22.11% of its value and trillions of investor equity. The Federal Government pushed a $700 billion bail-out through Congress to rescue the beleaguered financial institutions. The collapse of the financial system in the fall of 2008 was likened to an earthquake. In reality, what happened was more like a shift of tectonic plates.

In 1912 a German scientist, Alfred Wegener, proposed that the continents were once joined together as one giant land mass called Pangea.

About 200 million years ago the continents began to drift apart as the globe separated into eight distinct tectonic plates. History will record that the financial tectonic plates of our world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. They have not stopped moving and the outcome of where they will end up remains uncertain.

About 200 million years ago the continents began to drift apart as the globe separated into eight distinct tectonic plates. History will record that the financial tectonic plates of our world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. They have not stopped moving and the outcome of where they will end up remains uncertain.

PART ONE – THE AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY

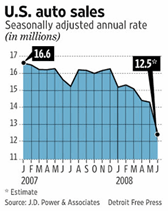

Edsel, Packer, Studebaker, Hudson, Nash, AMC – the demise of these brands may have seemed tragic at the time, but were actually a sign of industrial health. In contrast, for the last fifty years the American automobile industry has been static. Despite the proliferation of Japanese, Korean and German imports, General Motors, Ford and Chrysler managed to hold on to a majority of the domestic market, with a dizzying stable of makes and models that grew to near 17 million new car sales in 2007. That epoch is now over. The tectonic plates have shifted under the automotive business and a year from now, the industry will bear little resemblance to the static structure of the last fifty years.

Fifty years ago General Motors owned more than 50% of the American market and automobile jobs made up one seventh of the US workforce. It was said that when GM sneezed the US economy caught a cold. GM shares now sell for less than a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now GM is about to enter bankruptcy.

Fifty years ago General Motors owned more than 50% of the American market and automobile jobs made up one seventh of the US workforce. It was said that when GM sneezed the US economy caught a cold. GM shares now sell for less than a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now GM is about to enter bankruptcy.

The brands are dissolving, Oldsmobile was the first casualty. Pontiac and Hummer have been discontinued. When they reorganize, eleven hundred dealers will be terminated. General Motors will close all its plants for three months this summer. Many will never reopen. The New GM, to be known as Government Motors, will be owned by the UAW (20%) and the Federal Government (70%). Twenty billion of tax-payer loans will be converted to ownership to make the UAW pensions liquid. The debt holders will see their senior $27 billion investment converted into just 10% of stock. The shareholders will be wiped out.

The New GM will become the platform for small fuel efficient cars, hybrids, electric vehicles and experimental technologies mandated by an ever demanding government. Its shareholders vanquished, The New GM will bear no resemblance to the car company that we have known for the last 50 years. Can the Chevy Volt rescue GM? The answer is no.

The New GM will become the platform for small fuel efficient cars, hybrids, electric vehicles and experimental technologies mandated by an ever demanding government. Its shareholders vanquished, The New GM will bear no resemblance to the car company that we have known for the last 50 years. Can the Chevy Volt rescue GM? The answer is no.

GM will continue to shrink as their SAAB and Saturn franchises are sold off to the Chinese. China’s automobile sales are up 10% this year versus declines of 23% in the US and 15% in Europe. Chinese automobile manufacturers are grabbing market share, 30% this year versus 26% in 2008, while their competitors are distracted. Chinese companies unknown to Americans like Geely Motors, Chery Automobiles or BYD Co. will buy SAAB or Saturn for their dealer network. Warren Buffett invested $230 million into BYD, a firm that has been manufacturing cars for just six years. They already provide batteries to Ford and GM and soon will be building the world’s least expensive mass produced hybrid and electric vehicles. Geely plans to triple its domestic sales to 700,000 by 2015 and Chery plans to introduce 36 new models over the next two years.

Chrysler is in far worse shape and will likely never recover. The Federal Government already forced it into bankruptcy. Seven hundred and eighty nine dealers have been told that their franchises are terminated. Its shotgun marriage to Fiat will look more like a surgical amputation of unnecessary body parts than a marriage. If Fiat remains in the game, they will do so for the Jeep brand and a portion of the dealer network. Like Oldsmobile and Pontiac, Plymouth and Dodge brands are doomed as well as most of the Chrysler line. No one will mourn the demise of the Crossfire, Pacifica, Sebring, or the PT Cruiser. Fiat should keep the new Chrysler 300, a beautiful design that deserves to be built. Chrysler has not produced many stars in the last few decades. The trail blazing design of the 300 brought the full size sedan back from the dead.

Chrysler will jettison the weakest of its dealers in bankruptcy. Fiat will retain the big dealers in the network. They will bring the stunning and iconic Fiat 500 to America, a fuel efficient small car that will enjoy the same success as Volkswagen’s retro Beetle. Fiat will also use the dealer network to bring the Alfa-Romeo back to America. The Fiat-Jeep-Alfa dealer of the future will bear no resemblance to the staid Chrysler-Dodge-Plymouth dealer of today.

The surprising winner among the American troika of manufacturers is the Ford Motor Company. Ford and Lincoln will survive because they took no government bail-out money. Mercury may not survive but Ford and Lincoln should make it through the transition. The new Ford-Lincoln will be the refuge for auto enthusiasts who want attractive fast and powerful cars. Ford will become the Apple of the auto business, doing its own thing and flaunting political correctness and conventional wisdom. Ford’s namesake CEO has been an environmentalist for many years so Ford was well into fuel economy and hybrids before the tectonic plates began to move last fall. At just $5.00 per share, Ford is a tantalizing buy for the long term.

One can no longer call Mercedes, BMW, Toyota and Honda imports as many of their cars are made entirely in the U.S. The Japanese system is different than the American counterpart although we are drifting toward their model. The Japanese government plays a heavy hand in their industry, subsidizing the encroachment into new markets until the brands have stabilized market share. But they are not immune. Toyota lost $7.7 billion in the last quarter – even more than GM.

True imports like Volkswagen will weather the storm because they were well positioned with small fuel efficient cars long before the tectonic plates began to shift. VW is making a huge bet that oil will top $100/barrel again soon and their fuel efficient and clean diesels will be accepted by American drivers.

The biggest winner is obviously the UAW and their pensions which have been bailed out with tax payer money by an administration beholden to its labor supporters. Who will be the biggest loser? Clearly, it will be America’s small towns. Our small towns will lose their local dealer and their choice in automobiles. They will be forced to buy the brand that remains in town or drive scores of miles to the next closest dealer for service. Most small town auto dealers were also the most generous members of the community. Charitable giving and support will wither as will local sales tax revenues when the big ticket automobile sales tax revenues disappear. Ironically, as the plates continue to shift, America’s small towns could be decimated by the changes in the automobile industry as they were one hundred years ago when the automobile shifted millions from rural communities to the cities.

A year from now the landscape of America will be forever changed but the plates will continue to shift. Five years from now, will American ingenuity bring about a renaissance of the American automobile industry? Or, will what is left of this industry be gobbled up by the Chinese and the Korean manufacturers as the Japanese did in the 70s and 80s? The key issue may be what role the government will play. Will Americans buy cars designed by government bureaucrats and built by the unions that own the factories? Will an administration devoted to “coercing” Americans out of their cars be able to simultaneously save the auto industry?

***********************************

This is the first in a series on the Changing Landscape of America. Future articles will discuss real estate, politics, healthcare and other aspects of our economy and our society. Robert J. Cristiano PhD is a successful real estate developer and the Real Estate Professional in Residence at Chapman University in Orange, CA.

The city of Philadelphia lost 550,000 residents between 1950 and 2000, yet 76 percent of the suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan area (See lead picture of Philadelpia downtown).

The city of Philadelphia lost 550,000 residents between 1950 and 2000, yet 76 percent of the suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan area (See lead picture of Philadelpia downtown). The central city of Lisbon experienced a 30 percent population decline from 1965 to 2000. Yet suburban Lisbon’s growth was 80 percent from outside.

The central city of Lisbon experienced a 30 percent population decline from 1965 to 2000. Yet suburban Lisbon’s growth was 80 percent from outside.

The core city of Tokyo (which really doesn’t exist except as 23 separate subdivisions or kus of a city abolished during World War II) lost more than 700,000 residents from 1965 to 2000. Tokyo’s suburbs, however, attracted more than 90 percent of their growth from region.

The core city of Tokyo (which really doesn’t exist except as 23 separate subdivisions or kus of a city abolished during World War II) lost more than 700,000 residents from 1965 to 2000. Tokyo’s suburbs, however, attracted more than 90 percent of their growth from region.