It was widely reported that the Great Recession and subsequent economic malaise changed the geography of America. Suburbs, particularly in the Sun Belt, were becoming the “new slums” as people flocked back to dense core cities.

Yet an analysis of post-2007 population trends by demographer Wendell Cox in the 111 U.S. metro areas with more than 200,000 residents reveals something both very different from the conventional wisdom and at the same time very familiar. Virtually all of the 20 that have added the most residents from 2007 to 2012 are in the Old Confederacy, the Intermountain West and suburbs of larger cities, notably in California. The lone exception to this pattern is No. 15 Portland. The bottom line: growth is still fastest in the Sun Belt, in suburban cities and lower-density, spread out municipalities.

The No. 1 city on our list, New Orleans, fits this picture to a degree as a quintessentially Southern city, but it’s a bit of an anomaly. Its fast growth is partially a rebound effect from its massive population loss after Katrina, but is also a function of a striking economic revival that I have seen firsthand as a consultant in the area.

Since 2007 New Orleans’ population has grown 28% to 370,000. Many are newcomers who came, at least initially, to rebuild the city. But the city is still way below the 2002 population of 472,000, much less its high of 628,000 in 1960.

New Orleans is one of six cities where the population of the core has grown more in total numbers than the surrounding suburbs. (The other five are New York; San Jose, Calif.; Providence, R.I.; Columbus, Ohio; and San Antonio.) This is also a product of the fact that, when the Greater New Orleans region began to recover, the return to the suburban regions, for the most part, came before that to the city.

Nothing in the data, however suggests a revival of the older, dense “legacy” cities that were typical of the late 19th century and pre-war era. Most of the fastest-growing big cities since 2007 are of the sprawling post-1945 Sun Belt variety, including Charlotte, N.C. (No. 4); Ft. Worth, Texas (No. 6); Austin, Texas, (10th); El Paso, Texas (11th); Raleigh, N.C. (12th); and Oklahoma City (18th). Some of the fastest-growers are also outside the major metropolitan areas, such as No. 5 Bakersfield in California’s Central Valley, the North Carolina cities of Greensboro and Durham, (9th and 14th, respectively), and Corpus Christi, Texas (16th).

Among the big Northeast cities, the best performer is Washington (27th with 7.8% population growth) followed by Boston (71st, 2.2%). New York has managed only 0.3% population growth since 2007 (88th). Among other leading U.S. cities San Francisco’s population is up 3.3%, Los Angeles has grown 2.1%, and Chicago’s population has dropped 3.4%.

The other somewhat surprising result is the strong performance of more purely suburban cities, that is, ones that have grown up since car ownership became nearly universal. They are not the historic cores of their regions but have developed into major employment centers with housing primarily made up of single-family residences. These include the city that has grown the second most in the U.S. since 2007: Chula Vista, a San Diego suburb close to the Mexican border, whose population expanded 17.7%. It’s followed in third place by the Los Angeles suburb of Irvine (16.3%); No. 7 Irving, Texas; and the California cities of Fremont (13th) , located just east of San Jose-Silicon Valley, and Oxnard (17th), north of Los Angeles.

What do these results tell us? First, that Americans continue to move decisively to both lower-density, job-creating cities and to those less dense areas of major metropolitan areas particularly where single-family houses, good schools and jobs are plentiful.

Irvine, a planned postwar city of some 230,000 which ranks as the country’s seventh-wealthiest municipality, has three jobs for every resident; roughly two in five residents work in the city. Irvine’s 16.3% growth rate since 2007 has been bolstered by a strong inflow of Asians. Once overwhelmingly white, Irvine’s population is now roughly 40% Asian and 9% Hispanic.

Similarly, Irving, Texas, also thrived through the recession. Like Irvine this Dallas-area suburb is a major job center. Headquarters for Nokia , NEC Corporation of America, Blackberry, and Exxon Mobil, Irving’s population has soared over 13% over the past five years to 225,000.

This contrasts with some similarly sized suburbs that boomed in the first part of the decade. North Las Vegas added 80,000 people between 2002 and 2007 but its growth slowed down considerably as the Nevada economy cratered. This extension of Las Vegas has added a relatively paltry 12,000 people since 2007. With Phoenix losing 3.2% of its population since ’07, the nearby former boomtowns of Mesa and Scottsdale have also seen net outflows of residents.

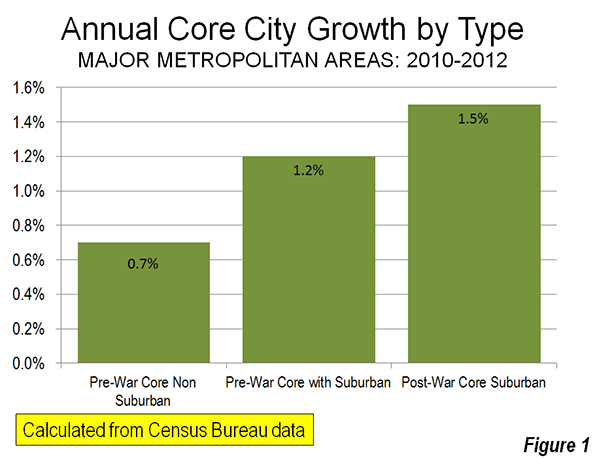

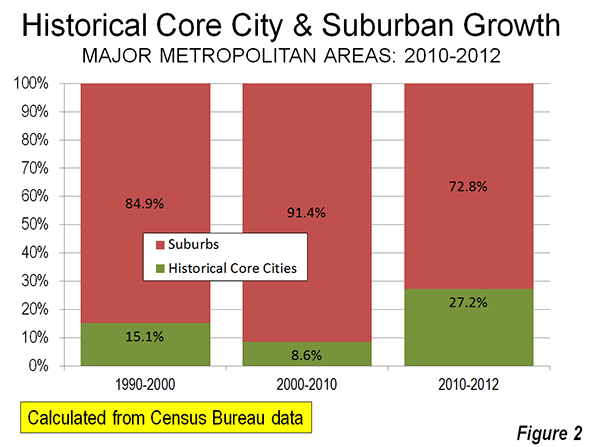

Migration numbers for 2010 to 2012 alone hammer home that suburban areas are continuing to attract people, and that the more dense core areas do not generally perform as well. Although their growth has slowed compared to the last decade, suburban locales, with roughly three-quarters of all residents of metropolitan areas, have added many more people than their core counterparts.

Where do we go from here? The urban future will continue to evolve in directions that contradict the prevailing conventional wisdom of a shift toward more crowded living. The continued dispersion of America’s population is evidenced by the persistent, and surprising, strength of suburban towns, as well as the low-density cities of Texas and the Plains. The key to growth in the next decade may depend largely on whether these rising municipalities can continue to create the jobs, favorable educational environment and amenities necessary to attract more newcomers in the future.

| MUNICIPALITIES OVER 200,000 IN 2012 | |||||

| 25 Fastest Growing 2007-2012 | |||||

| POPULATION | CHANGE | ||||

| RANK | MUNICIPALITY | 2002 | 2007 | 2012 | 2007-2012 |

| 1 | New Orleans, Louisiana | 472,744 | 288,113 | 369,250 | 28.2% |

| 2 | Chula Vista, California | 194,167 | 214,506 | 252,422 | 17.7% |

| 3 | Irvine, California | 162,205 | 197,714 | 229,985 | 16.3% |

| 4 | Charlotte, North Carolina | 590,857 | 669,690 | 775,202 | 15.8% |

| 5 | Bakersfield, California | 259,146 | 312,454 | 358,597 | 14.8% |

| 6 | Fort Worth, Texas | 570,808 | 680,433 | 777,992 | 14.3% |

| 7 | Irving, Texas | 195,764 | 198,119 | 225,427 | 13.8% |

| 8 | Laredo, Texas | 189,954 | 215,789 | 244,731 | 13.4% |

| 9 | Greensboro, North Carolina | 231,415 | 245,767 | 277,080 | 12.7% |

| 10 | Austin, Texas | 684,634 | 749,120 | 842,592 | 12.5% |

| 11 | El Paso, Texas | 570,336 | 600,402 | 672,538 | 12.0% |

| 12 | Raleigh, North Carolina | 313,829 | 379,106 | 423,179 | 11.6% |

| 13 | Fremont, California | 205,034 | 199,187 | 221,986 | 11.4% |

| 14 | Durham, North Carolina | 196,432 | 216,943 | 239,358 | 10.3% |

| 15 | Portland, Oregon | 538,803 | 546,747 | 603,106 | 10.3% |

| 16 | Corpus Christi, Texas | 276,877 | 283,445 | 312,195 | 10.1% |

| 17 | Oxnard, California | 176,594 | 183,235 | 201,555 | 10.0% |

| 18 | Oklahoma, Oklahoma | 519,100 | 545,910 | 599,199 | 9.8% |

| 19 | Aurora, Colorado | 282,707 | 309,007 | 339,030 | 9.7% |

| 20 | Denver, Colorado | 561,072 | 578,789 | 634,265 | 9.6% |

| 21 | Fontana, California | 158,916 | 184,814 | 201,812 | 9.2% |

| 22 | Fresno, California | 442,987 | 465,669 | 505,882 | 8.6% |

| 23 | Orlando, Florida | 199,358 | 230,239 | 249,562 | 8.4% |

| 24 | Colorado Springs, Colorado | 376,341 | 399,751 | 431,834 | 8.0% |

| 25 | Riverside, California | 272,814 | 290,601 | 313,673 | 7.9% |

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com.

New Orleans photo by Bigstock.