A review of the most recent internal migration (domestic migration) in England and Wales reveals some surprises. The latest data covers the one year ended June 30, 2014. It was published by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) and provides estimates at least down to the local authority area (municipality). In this regard, is positioned along with a number of European nations and the Australian Bureau of statistics well ahead of the US Census Bureau, which provides estimates only to the county level.

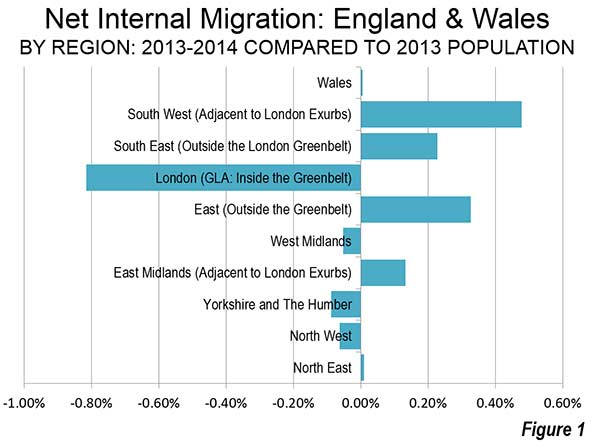

The Regions

On a regional level, there was little movement outside the southern half of England. England is divided into nine regions. Three of the northern and middle regions lost modest numbers of internal migrants, ranging from a minus 0.05% (minus 3,000 people) in the West Midlands, which contains England’s second largest city, Birmingham. There was loss of 0.06% (minus 7,100 people) in the North West, where Manchester and Liverpool are located. There was a 0.09% loss (minus 4,700 people) in Yorkshire and the Humber, where Leeds and Sheffield are located (Figure 1).

The North East, which contains the city of Newcastle, has long been an area of economic hardship and is of danger of becoming "Britains Detroit" according to The Guardian. Yet the North East experienced a small gain of 0.01% in internal migrants (500 people). The largest gain outside southern England was in the East Midlands, which includes Leicester and Nottingham, attracted a net 0.13 percent in new migrants (6,200 people). Wales (largest city Cardiff) also had a 0.1% gain in internal migrants (200 peopled).

London (the Greater London Authority) lost by far the largest percentage of its population to internal migration, at minus 0.82 percent, or 68,600 people. This may be particularly surprising because London has recently reached its all-time population peak, having exceeded its pre-World War II 1939 estimated level. Yet virtually all of London’s huge population gain has been from natural growth (births minus deaths) and international migration. In recent years, this growth stems from strong gains in migration from a European Union countries, between which there is virtually unrestricted immigration.

But Londoners, whether born in Great Britain or those who arrived before 2013, have been moving in large numbers to the exurbs beyond the greenbelt for some time and even farther away. The two large exurban regions have attracted many migrants. The East, which includes such well-known localities as Cambridge, Luton, Milton Keynes and St. Albans added the 0.33 percent to its population through internal migration. The South East, which includes localities like Oxford, Windsor, Dover and the entrance to the Euro tunnel to France added a somewhat smaller 0.23 percent.

But some Londoners appear to be moving even farther away. The largest growth was in the South West region, which lies at least 70 miles (125 kilometers) from Trafalgar Square in London. The South West is home to such places as Bristol, Bath, Salisbury and Cornwall. The South West added 0.48 percent to its population through.

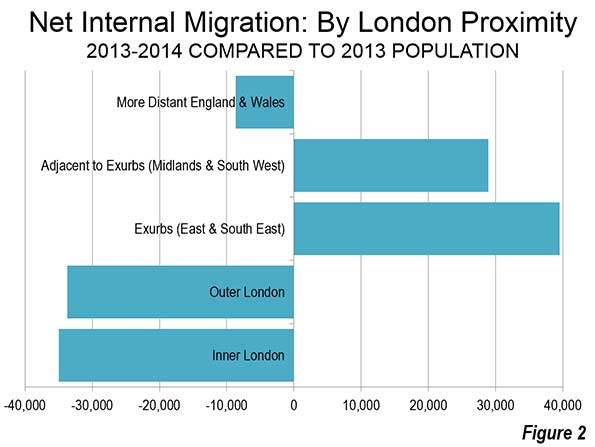

London and Environs

During 2013-2014, the dominant trend was movement away from London to the exurbs and regions just beyond the exurbs, with a less dominant trend away from the balance of England and Wales. Virtually all the internal migration growth was in the London Exurbs (East and South East) and the adjacent areas, the South West, East Midlands and West Midlands (Figure 2). Nearly all the loss was in London. Inner London, suffered the largest domestic migration loss, at 1.05 percent of its population (minus 35,000). Inner London, at 3.3 million remains well below its population peak of 4.5 million, reached nearly 115 years ago (1901). Outer London, consisting of the large tracts of semidetached and detached housing built in the inter-war years lost a smaller 0.66 percent of its population to internal migration (minus 33,700). Outer London now has a population of approximately 5.1 million, one-half larger than Inner London.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) explains that London attracts internal migrants up to age 29. But, the internal outmigration of people 30 and above more than cancels this out. ONS explains:

"A key factor for people in their 30s and 40s who move out of London could be the cost of housing. Young couples wishing to buy their first house, or a larger one for a growing family, may find prices in London prohibitively expensive and therefore choose to live outside of London."

ONS adds:

"Another important reason may be that people with children are more likely to move out of London because of environmental or social factors. For example, they may be seeking somewhere greener and quieter, and may also perceive that a less urban neighbourhood offers a better social and educational environment for children. Moves of adults with children also explains why there is a net outflow of children from London."

ONS further indicates that there is net migration from London of older citizens, including those over 90 (the highest age category reported upon). These are trends similar to those we have identified in the United States some of which were opposite the conventional wisdom (See: Driving Farther to Qualify in Portland, Urban Core Millennials? A Matter of Perspective, Exodus of the School Children, and Seniors Dispersing Away from the Urban Cores)

Greatest Gains and Losses

Even so, London had one local authority area with the greatest internal migration gain: the historic City of London. However, this area, which is the core of the central business district, has few residents. Even after the internal migration gain (1.80 percent), the city still has fewer than 8,000 residents. The other largest gainers in numbers were found in the London exurbs or the South West, with the exception of Fylde, which is located in Lancashire (the North West), adjacent to the resort of Blackpool.

London had nine of the 10 local authority areas with the greatest internal migration losses (out of 348). The largest loss was in the inner London borough of Newham (minus 2.68%). The one non-London local authority area in the bottom 10 was Pendle, in Lancashire (the North West).

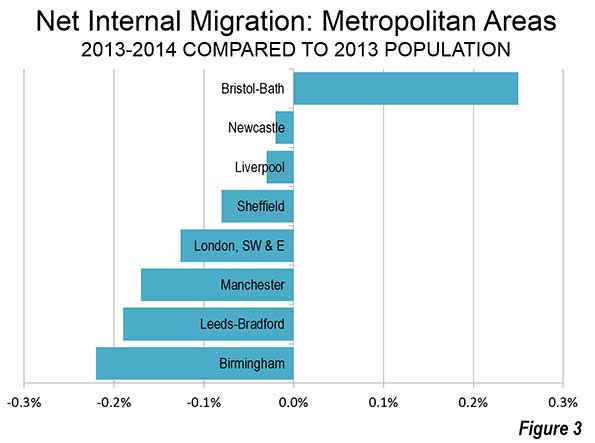

Metropolitan Areas

Only one of the larger metropolitan areas experienced a net internal migration gain. The Bristol – Bath area (ceremonial Avon County), located in the South West gained 0.25 percent (Figure 3).

Two metropolitan areas that have long experienced serious economic declines suffered only modest losses. Newcastle (Tyne and Wear Metropolitan County) lost only 0.2 percent of its population to internal migration. Liverpool, with a central municipality that dropped from a population of 856,000 in 1931 to 439,000 in 2001 (after which modest growth returned), had an internal migration loss of 0.03 percent. Sheffield (South Yorkshire Metropolitan County) lost 0.08% of its population to net internal migration.

In view of the relative fortunes of London and Liverpool over the last century, it is especially surprising that the London region, including the exurbs, lost internal migration at a rate four times that of Liverpool (0.13%).

Manchester (Greater Manchester Metropolitan County) experienced a net internal migration loss of 0.17 percent, and Leeds-Bradford (West Yorkshire Metropolitan County). Birmingham (West Midlands Metropolitan County) have the greatest loss at -0.22 percent.

More Dispersion

By far the largest net internal migration numbers are in the south of England, reflecting strong trends of decentralization away from London, to the East and the South East. But, by far the largest recipient of internal migration is the South West, beyond even the exurbs. This is another confirmation of the dispersing pattern of development, as has been observed in virtually all of the world’s megacities.

————–

Note: The United Kingdom does not formally designate metropolitan areas. This article uses metropolitan and former (ceremonial) counties to approximate metropolitan areas.

Photograph: Local authority of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire (South East of England), by author

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.

He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.