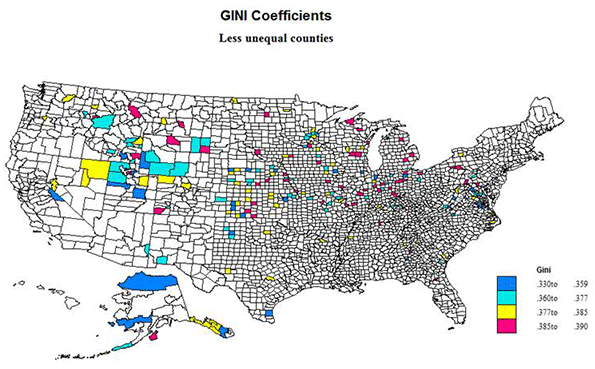

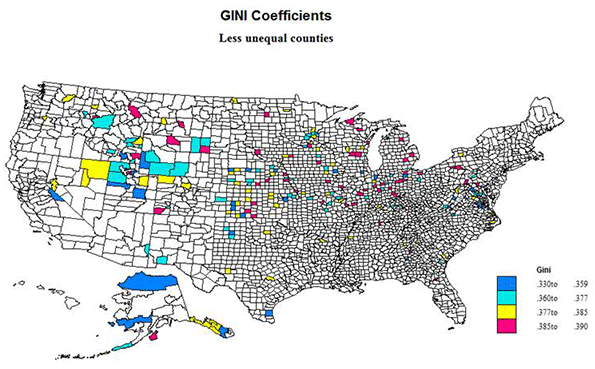

The extreme and rising inequality of income and wealth in the United States has been exhaustively reported and analyzed, including by me. Incomes are strikingly unequal just about everywhere, but not to the same degree. To discover a more egalitarian America, I used US Census American Community Survey data (2007-2011) estimates of the Gini coefficients of all US counties and equivalents. The Gini coefficient is a measure of the percent departure of a line of accumulated population versus accumulated income, from the lowest to the highest and the straight line if everyone had the same equal income.

The index would be 0 if all were equal, 1.0 if only 1 person had all the income. The median US counties, dozens of them, have a Gini of .43, which is in fact pretty extreme, far higher than in 1974, when it was .37. But the overall US figure is .47 (.41 in 1975), because larger counties tend to be more unequal than smaller, skewing the average. Examples of a median .43 county are Winnebago, WI (Oshkosh!), Klamath, OR, and Arlington, VA, and a good example of the average US county is Jackson, MO (Kansas City!). The lowest Gini for the US is .33 (Yakutat, AK and Power, ID) and the highest is no surprise at .59, New York county (Manhattan). It is revealing and horrific that our lowest value of .33 is that of Sweden (and most of Scandinavia), Germany is only .35 and the lowest in the world is evidently Switzerland, despite those rich bankers, at .31.

Is this a Great Country or What?

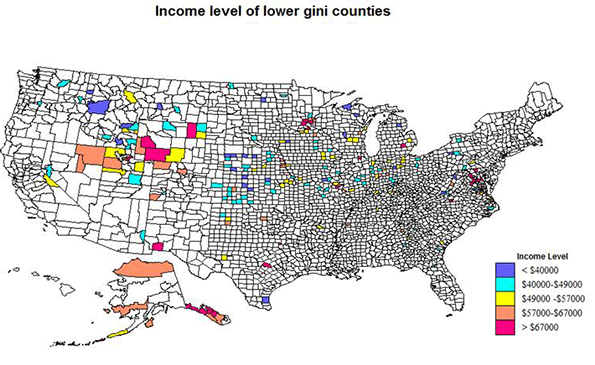

I mapped only the 208 counties with the lowest Gini indices, those under .39, in two ways, first by the Gini values and then by groups of these counties sorted by median incomes. Only 10 have values below .35. In 1975, 11 counties had Ginis bellow .27. States with the highest number or share of less unequal counties include Alaska, 10, Idaho, 11, Indiana, 15, Iowa, 10, Kansas, 18, Minnesota, 11, Nebraska, 17, Utah, 7, Virginia, 13 and Wyoming, 8. Except for Alaska, there is an evident north central bias: band of less unequal counties from Virginia to Idaho-Nevada, with epicenter at the junctions of Utah, Idaho and Wyoming.

States without any qualifying as less unequal counties (with Ginis under .39) are Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Rhode Island and South Carolina. Large California has only one, as does New York, and large Texas only 7.

Size of Counties

A problem with the data is that small population size of many of the counties render the ACS estimates somewhat uncertain. Thirteen have fewer than 500 households, 25 have fewer than 1000. It is reasonable that smaller rural counties, e.g., in the Plains states, might have less inequality because of the homestead settlement history and the absence of slavery, but there is still uncertainty due to small sample size. Of the counties with under 1000 households, 8 are in NE, 5 in AK, 3 in KS, 2 in CO, MT and TX, and 1 in ID, N and WA.

At the other end, 28 counties have more than 25,000 households, and 5 have over 100,000. The largest are an interesting set. All are suburban, or even exurban, and most are fairly high income, essentially homogeneously middle class. The six largest are Williamson, TX, King William, VA, St. Charles, MO, Anoka, MN, Loudoun, VA and Davis, UT. These are also among the richest counties on the list.

It might be meaningful that some of these counties, as around Washington, DC, Baltimore and Austin, TX, have high levels of government employees, while their minority levels are quite low.

Lower inequality, but High in Minorities

This unlikely combination does occur, although only 7 of the 208 counties have minority shares (percentages) above .5: TX, 3, Kenedy, Moore and Reagan; KS, 2, Ford and Seward; AZ 1, Greenlee, and AK, Aleutians 1. The TX, KS and AZ counties are all Hispanic, and high in energy development for TX and KS. The AK county is Asian. No county has a black population majority. Surry county, VA, at 47% black, is highest share of black population, located and exurban between Richmond and Norfolk.

The Lowest Ginis, Under .36

Thirty-one counties have Gini levels under .36 (Still high of course!) Only 10 are under .35. These vary in size from tiny Kenedy, TX (147 households) to Loudon, VA with 105,000. The distribution by state is

VA 7: King William, Prince George, Surry, Craig, Greene, Loudon, King and Queen

KS 4: Meade, Wabaunsee, Wichita, Kearny

AK 3: Yakutat, Bristol Bay, North Slope

UT 3: Morgan, Emery, Juab

NE 3: Blaine, Stanton, Grant

TX 2: Kenedy and Carson.

Several states with one county: CA, Mono, GA, Chattahoochee, ID, Power, IL, Kendall, IN, Jasper, IA, Cedar, KY, Spencer, OH, Putnam, and WY, Lincoln.

These are distributed in a similar way to the 208 lower Gini counties, with the exception of the much larger number in VA, and not just in the WDC area! UT and AK stand out, as do neighbor states of KS and NE. The AK set is high in minorities (Native Americans, Asians), as is Kenedy, TX (Hispanic). The VA set includes suburban Richmond and Washington DC counties, exurban to rural Chesapeake Bay counties, a tiny Allegheny mountain county and suburban Charlottesville. ID, UT, KY, KS, IL, IN and GA have suburban counties, KS and TX energy growth counties, and NE, WY, UT and CA fairly remote rural counties, the latter three recreational.

Less unequal counties by income level

Lower income counties: 27 counties have median household incomes below $40,000. By state these are

NE 5: Garfield, Hooker, Blaine, Grant. Hayes

ID 5: Idaho, Lewis, Power, Benewah, Clark

KS 4: Cloud, Norton, Trego, Rush

MI 2: Oscoda, Ontonagon

WV 2: Grant, Monroe

WI 2: Adams, Florence

Several states with one county, including PA, Forest: TX, Kenedy: MT, Golden Valley: IN, Jay;

IA, Osceola,; ND, Griggs; and MO, Monroe,

The dominance of neighboring KS and NE is noteworthy, as is the large number and share in Idaho. Eight of the counties are small, with under 1000 households, and only 4 have over 40,000. Thus most of the counties are rural and small town, resource oriented, and often with small manufactures. The counties in upper Michigan and Wisconsin are similar in character.

Higher income counties at the other end comprise 28, with median household incomes above $67,000. By state these are:

VA 7: Loudoun, Stafford, Prince William, Spotsylvania, Manassas Park, New Kent, King George

AK 4: Juneau, Denali, Skagway, North Slope

MN 4: Scott, Sherburne, Anoka, Wright

MD 3: Calvert, Charles, Carroll

WY 3; Campbell, Sublette, Sweetwater

TX 2; Rockwall, Williamson

Several with one county: NM, Los Alamos: UT, Morgan; MO, St Charles; MI, Livingston; IL, Kendall

The 9 richest counties include 6 suburban or exurban around Washington DC and Baltimore, suggesting the importance of federal employment, and federal oriented Los Alamos, NM, Rockwall is suburban Dallas, Scott suburban Minneapolis. Other suburban and exurban counties are in UT, MO, and MN (3 more!), VA (4 more), MI, IL, and TX. Higher income rural small town areas are in AK (4) and WY (3).

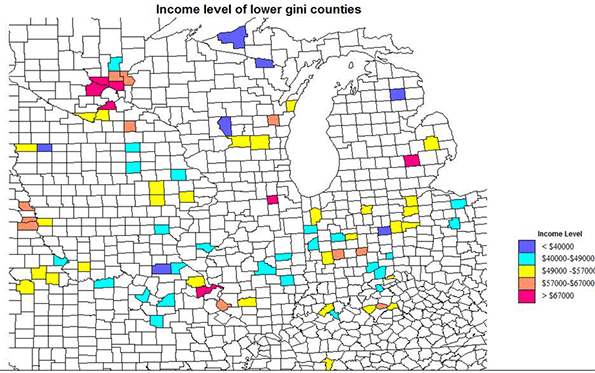

Middle Income Less Unequal Counties

The middle group of 52 counties with median household incomes between $49,000 and $57,000 are more varied and complex. By state

IN 6: Jasper, Ohio, Putnam, Spencer, Tipton and Whitley

IA 5: Iowa, Lyon, Cedar, Mills, Benton

KS 3: Jackson, Wabaunsee, Jefferson

UT 3: Juab, Duchesne, Box Elder

OH 4: Mercer, Henry, Auglaize, Putnam

WI 2: Kewaunee, Dodge, Columbia

MN 2: Le Sueur, Nicollet

ID 2: Jefferson, Teton

MO, 2, Clinton, Lincoln

WY 2: Weston, Carbon,

KY, 2, Anderson, Bullitt

TX, Reagan

GA 2: Pike, Effingham

VA 2: Surry, Greene

NE 2: Hamilton, Kearny

AK, Aleutians, AR, Saline, CA, Mono, IL, Washington, MI, Lapeer

MT Lewis and Clark. OR, Hood River, PA, Perry, TN, Cheatham, NC Currituck

None have under 1000 households, and 21 have 10,000 or more. The largest, Saline, AR, has 41,000 (suburban Little Rock).

These tend to prevail across the north central states from OH west to UT, and include many small town and small city regional centers. Several are free-standing small town counties, a few are suburban to larger cities, such as Nashville and Little Rock, but the most are far suburban or exurban to smaller metro areas.

The small map inset centered on Indiana illustrates these patterns.

Conclusions

The geography of these less unequal counties is unusual. Not one is a metropolitan core county, large or small. Not one is a majority black county. While there are many suburban counties, almost all are in a few clusters, VA-MD, ID-UT, or in the upper Midwest, especially MN. A large number are exurban, just beyond the official metro areas, mostly across the north, but with a few in the south. And, most old-fashioned and reassuring, quite a number are freestanding small city and small town, micropolitan or smaller counties, most notably in the Northern Plains and Rocky Mountain states, and apparently doing well with a resource and small industrial economy.

Contrasting the Most Unequal Counties

OK, how different is the geography of the most unequal counties? The US has 30 counties with Gini indices over .53, culminating in New York (Manhattan) at almost .6. These are indeed quite different, as race plays a dominant role, but not a universal one.

23 of the 30 are in the south, and 17 of these have high black population shares, including core metropolitan counties, the District of Columbia, Fulton (Atlanta). Orleans (New Orleans), and Richmond, VA. Outside the south, 6 of the 8 counties also have a high minority share, New York (Manhattan), Westchester, Essex, NJ (Newark), Sioux, SD (reservation), and Harding, NM (Latino), leaving only tiny Mineral CO (recreation), and Fairfield CT (super rich suburban-exurban NY).

Six counties in the south do not have high minority shares, Decatur, TN (west central on the Tennessee river), Baylor, TX , exurban Wichita Falls, Llano, TX , exurban Austin and tiny Borden, TX, Galax city, VA, far southwest, and Watauga, NC, home of Appalachian State University.

Race clearly is the most common basis for extreme inequality, but exurban counties close to rich metropolitan centers may also have high class differentials, as do some recreation dependent areas.

Richard Morrill is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Washington. His research interests include: political geography (voting behavior, redistricting, local governance), population/demography/settlement/migration, urban geography and planning, urban transportation (i.e., old fashioned generalist).