For any who had been following demographic trends closely in Western Europe, it is long been obvious that suburbanization was following generally the same track as in Canada (more than 75 percent suburban), Australia and the United States (85 percent suburban). Nearly all growth in the major cities has been in the suburbs for the last four decades.

The massive postwar automobile oriented suburbanization of Europe started a bit later than in the Western offshoots of the British Empire as the fabled economic historian Angus Maddison called them. It took a while for Western Europe to recover from World War II, but by 1970 much had been restored.

This article reviews citywide population trends, divided into their core and suburban (or exurban) components from 1971 to 2011. This is a far more complicated exercise than reviewing the urban trends of Canada, Australia, and the United States. Ten years ago I published an examination of European trends relying principally on using data from the Ranally Metropolitan Areas, which had been established by my friend Richard Forstall, then at Rand McNally. Metropolitan areas are particularly difficult to compare across international lines because the few nations that designate them use different criteria and most nations do not designate them at all.

Regretfully, the internet and perhaps other commercial considerations made the Ranally Metropolitan Areas a thing of the past.

Data Difficulty in Western Europe

The only source that approaches consistency is the United Nations Urban Agglomerations (urban areas) list. In its latest iteration the list includes data from 1950 through projections to 2030 in five year increments for approximately 1700 cities around the world. But, the United Nations must rely on member states to provide the information, which is often not urban agglomeration data at all.

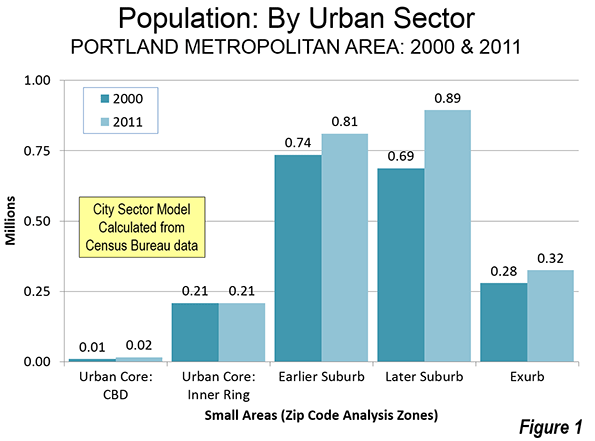

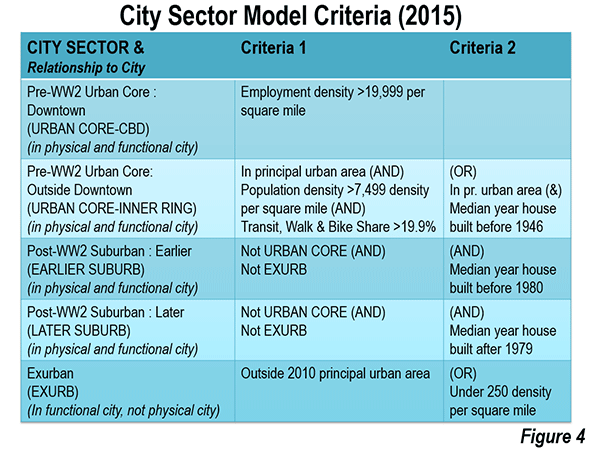

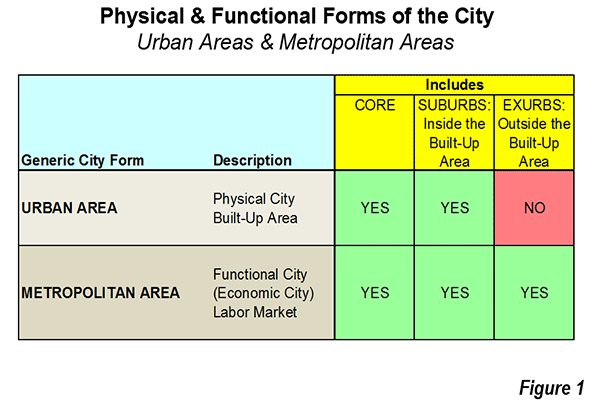

Some nations report urban area data. Others report metropolitan area data. Urban areas and metropolitan areas are not the same thing. Urban areas are built up areas defined by the extent of the urban form, rather than by jurisdictional boundaries (see Demographia World Urban Areas). Metropolitan areas encompass both the urban area and the economically connected areas to the outside (exurbs). The difference is that urban areas do not include exurbs and metropolitan areas do (Figure 1).

Some nations report only core municipality data, which is incomplete. Characterizing cities as only the core is rather like declaring a leg or a lung to be the same thing as a human body. These nations include Germany and Austria. Data for Valencia, Spain is also for the core municipality only.

Perhaps the best source for citywide trends over the last 40 years in Western Europe is the United Nations data. The results are reported for urban areas and metropolitan areas, ignoring the irrelevant reported core data. Cities are included that had a population of 750,000 or more in any year from 1970 to 2010 on the UN World Agglomerations list. As of 2011, there are 24 urban areas and 16 metropolitan areas with comparable United Nations data (Table).

How the Cities have Dispersed

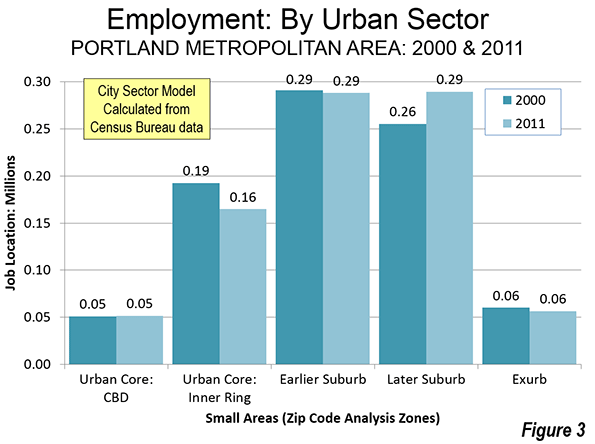

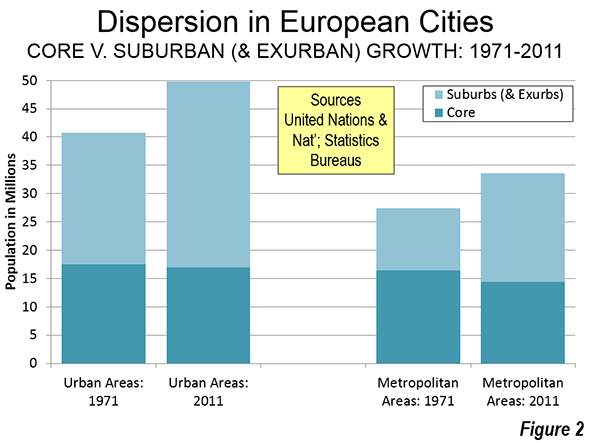

Among the urban areas, the suburbs monopolized population growth over the period (1971 to 2011). Overall, the 24 urban areas increased their population by 9.1 million residents. This was the combination of a 9.7 million increase in the suburbs and a 600,000 loss in the cores. With the core losses, the suburbs accounted for 107% of the urban area growth.

The monopolization of suburban and exurban growth was even greater in the 16 metropolitan areas. The overall citywide population increase was 6.2 million. This included 8.2 million in the suburbs and exurbs and the loss of 2.1 million in the cores.

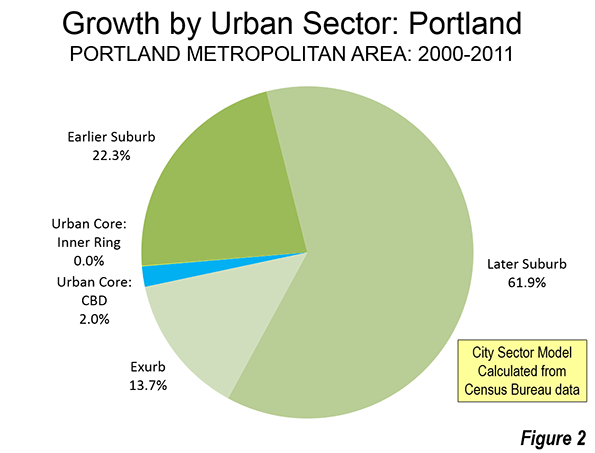

Combining these two different urban conceptions for statistical purposes shows how dominant suburban and exurban growth has been. In 1971, the cores and suburbs had about the same population. By 2011, the suburbs had grown to have 60% more residents than the cores (Figure 2).

Some of the disparities were large. In Madrid, the suburbs grew 450 percent between 1971 and 2011, compared to only 5 percent in the core. In Toulouse, the suburbs grew 327 percent, while the core edged up only 20 percent, while in Zurich, the suburbs grew 186 percent compared to the core decline of 12 percent.

Overall, core population performance exceeded that of the suburbs in only three of the 40 cases. The most significant is slow-growing Birmingham, which is closing in on its 1951 peak. Then there is Liverpool, which is managed to drop from the population peak of more than 850,000 in 1931 to under 475,000 in 2011. Liverpool’s loss over the 40 years was even less percentage wise than that of the suburbs. The core of Southampton also grew faster than the suburbs.

Core Resurgence

At the same time, it notable cores have reversed their previous loss patterns in recent years. Some resurgent cores remain well below their much earlier peaks. The ville de Paris has regained little more than 100,000 of its 800,000 loss since 1921. Inner London (Note) has regained much more (800,000), but still needs another 1.3 million to restore its 1901 peak (Outer London is so suburban that it provided much of the ammunition for the British anti-suburban movement). Others cores, like Stockholm and Madrid have risen above previous peaks.

As in the United States, this urban resurgence should not lead to a perception that suburbanites are "flocking" to the urban cores. Domestic migration data continues to show net population movements from the cores to the suburbs and exurbs. Much of the resurgence has been propelled by international migration since enlargement of the European Union (such as from the growing London core), which has virtually eliminated westward barriers to immigration from the less affluent former Soviet satellites. Even the core of Stockholm, now at its population peak, has lost domestic migration to the suburbs in Stockholm County in each of the last five years according to Statistics Sweden data.

Earlier Core Troughs

The forty-year perspective masks some huge core population losses that occurred earlier. Perhaps the most spectacular is Copenhagen, which dropped from 768,000 in 1950 to 464,000 in 1992, for a percentage loss near that of Detroit from 1950 to 1990. Copenhagen’s population loss was 40 percent, compared to Detroit’s 44 percent (See: Shrinking Cities, Chapter 2). Since 1992, the core of Copenhagen has made up only a quarter of its loss since 1950.

The core of Glasgow also suffered earlier losses. In 1931, the core municipality had a population nearing 1.1 million. By 1971, Glasgow became the first core municipality in the world to fall below 1,000,000 population after having achieved that status. Glasgow has since been followed by Naples, Turin and Detroit. Glasgow increased its population modestly after 2001, to just under 600,000.

The Missing Cities

What can be said about Germany and Austria, which do not provide data for either urban areas or metropolitan areas? If such data were available, it would likely show the same general trends. By the early 2000s, cores such as Berlin, Dresden, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Munich and Stuttgart had lost population from their peaks. Between 1987 and 2001, all growth in the Rhine-Ruhr, Western Europe’s third largest city, was in the suburbs and exurbs. This area, which defines the very term conurbation, may have been the first truly polycentric metropolitan area in the world, with its historic municipalities like Essen, Dusseldorf, Bochum, Gelsenkirchen, Oberhausen, Dortmund, Duisburg, Dusseldorf and Wuppertal. Vienna reached its population peak in 1910,when capital of the Austro-Hungarian under Emperor Franz Josef.

Better Data Ahead

Meanwhile, the state of urban statistics is improving significantly in Europe. It is to be expected that historical data would be non-comparable and cumbersome with Europe’s multiple nations. However, Eurostat now publishes its own, consistent metropolitan area data. Generally data is available back to the early or mid 2000s, which will make the lives of interested statisticians better in the future.

The suburbanization of Europe may be surprising to New World tourists, who rarely venture beyond the historical cores. I called this the Louvre Syndrome, which describes New World tourists who jealousy wonder why their cites cannot look like attractive European cores, but never experience, predictably, their extensive and less historically appealing suburbs. And why should they? Americans and Canadians go to Europe to see what’s different, not what’s similar.

What is similar is that the cities of Europe, like those in Japan and the New World have dispersed as they have become more affluent, a dynamic pointed out by Robert Bruegmann in Sprawl: A Short History. There is also considerable dispersion going on in developing world cities. There is also an imperative to disperse the inhuman densities and living conditions in many parts of African, Asia and South America. These include shantytowns like Dharavi in Mumbai, Kibera in Nairobi, Rio’s notorious favelas and in Manila, with its all too frequent fires that destroy thousands of homes at once.

| Core & Suburban Growth in Cities |

|

|

| Western Europe: 1971-2011 |

|

|

|

| Urban Areas (Urban Agglomerations) and Metropolitan Areas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population in 000s |

1971 Population |

2011 Population |

| |

UA/MA |

Core |

Suburbs |

UA/MA |

Core |

Suburbs |

| URBAN AREAS (URBAN AGGLOMERATIONS) |

|

|

|

| Amsterdam |

938 |

820 |

118 |

1,064 |

780 |

284 |

| Athens |

2,535 |

862 |

1,673 |

3,089 |

664 |

2,425 |

| Birmingham |

2,369 |

1,013 |

1,356 |

2,446 |

1,086 |

1,360 |

| Bordeaux |

590 |

254 |

336 |

853 |

239 |

614 |

| Dublin |

783 |

569 |

214 |

1,114 |

528 |

586 |

| Glasgow |

1,732 |

897 |

835 |

1,210 |

593 |

617 |

| Helsinki |

522 |

529 |

-7 |

1,134 |

588 |

546 |

| Lille |

912 |

233 |

679 |

1,020 |

228 |

792 |

| Liverpool |

1,253 |

607 |

646 |

865 |

466 |

399 |

| London |

7,787 |

2,959 |

4,828 |

10,297 |

3,232 |

7,065 |

| Lyon |

1,128 |

507 |

621 |

1,563 |

491 |

1,072 |

| Manchester |

2,391 |

542 |

1,849 |

2,559 |

503 |

2,056 |

| Marseille |

1,197 |

894 |

303 |

1,569 |

851 |

718 |

| Newcastle |

876 |

222 |

654 |

776 |

149 |

627 |

| Nice |

649 |

328 |

321 |

947 |

344 |

603 |

| Oslo |

643 |

488 |

155 |

916 |

599 |

317 |

| Paris |

8,278 |

2,504 |

5,774 |

10,537 |

2,250 |

8,287 |

| Rotterdam |

959 |

687 |

272 |

995 |

606 |

389 |

| Stockholm |

1,031 |

747 |

284 |

1,385 |

847 |

538 |

| Southampton |

740 |

213 |

527 |

857 |

254 |

603 |

| Thessaloniki |

557 |

340 |

217 |

754 |

325 |

429 |

| Toulouse |

476 |

372 |

104 |

891 |

447 |

444 |

| West Yorkshire |

1,705 |

506 |

1,199 |

1,787 |

475 |

1,312 |

| Zurich |

711 |

423 |

288 |

1,198 |

373 |

825 |

| Urban Areas |

40,763 |

17,516 |

23,247 |

49,824 |

16,918 |

32,906 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| METROPOLITAN AREAS (LABOR MARKETS) |

|

|

|

| Antwerp |

858 |

227 |

631 |

976 |

185 |

791 |

| Barcelona |

3,521 |

1,828 |

1,693 |

4,999 |

1,621 |

3,378 |

| Bergamo |

561 |

126 |

435 |

799 |

115 |

684 |

| Bologna |

746 |

488 |

258 |

766 |

371 |

395 |

| Brussels |

1,576 |

143 |

1,433 |

1,975 |

170 |

1,805 |

| Copenhagen |

1,338 |

626 |

712 |

1,207 |

540 |

667 |

| Florence |

725 |

460 |

265 |

694 |

358 |

336 |

| Genoa |

918 |

832 |

86 |

701 |

586 |

115 |

| Lisbon |

1,874 |

782 |

1,092 |

2,826 |

553 |

2,273 |

| Madrid |

3,595 |

3,121 |

474 |

5,870 |

3,265 |

2,605 |

| Milan |

3,040 |

1,732 |

1,308 |

3,065 |

1,242 |

1,823 |

| Naples |

2,019 |

1,267 |

752 |

2,213 |

962 |

1,251 |

| Palermo |

757 |

653 |

104 |

855 |

658 |

197 |

| Porto |

941 |

326 |

615 |

1,288 |

238 |

1,050 |

| Rome |

3,168 |

2,656 |

512 |

3,617 |

2,617 |

1,000 |

| Turin |

1,775 |

1,142 |

633 |

1,742 |

872 |

870 |

| Metropolitan Areas |

27,413 |

16,409 |

11,004 |

33,594 |

14,353 |

19,241 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

68,177 |

33,925 |

34,252 |

83,418 |

31,271 |

52,148 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Populaton Change |

1971 Population |

2011 Population |

| |

UA/MA |

Core |

Suburbs |

UA/MA |

Core |

Suburbs |

| URBAN AREAS (URBAN AGGLOMERATIONS) |

|

|

|

| Amsterdam |

126 |

-40 |

166 |

13% |

-5% |

141% |

| Athens |

553 |

-198 |

751 |

22% |

-23% |

45% |

| Birmingham |

77 |

73 |

4 |

3% |

7% |

0% |

| Bordeaux |

263 |

-15 |

278 |

45% |

-6% |

83% |

| Dublin |

331 |

-41 |

372 |

42% |

-7% |

173% |

| Glasgow |

-522 |

-304 |

-218 |

-30% |

-34% |

-26% |

| Helsinki |

611 |

59 |

552 |

117% |

11% |

|

| Lille |

108 |

-5 |

113 |

12% |

-2% |

17% |

| Liverpool |

-389 |

-141 |

-248 |

-31% |

-23% |

-38% |

| London |

2,510 |

273 |

2,237 |

32% |

9% |

46% |

| Lyon |

435 |

-16 |

450 |

39% |

-3% |

72% |

| Manchester |

169 |

-39 |

208 |

7% |

-7% |

11% |

| Marseille |

372 |

-43 |

415 |

31% |

-5% |

137% |

| Newcastle |

-101 |

-73 |

-28 |

-11% |

-33% |

-4% |

| Nice |

298 |

16 |

282 |

46% |

5% |

88% |

| Oslo |

272 |

111 |

161 |

42% |

23% |

104% |

| Paris |

2,259 |

-254 |

2,513 |

27% |

-10% |

44% |

| Rotterdam |

36 |

-81 |

117 |

4% |

-12% |

43% |

| Stockholm |

354 |

100 |

254 |

34% |

13% |

90% |

| Southampton |

118 |

41 |

77 |

16% |

19% |

15% |

| Thessaloniki |

197 |

-15 |

212 |

35% |

-4% |

97% |

| Toulouse |

415 |

75 |

340 |

87% |

20% |

327% |

| West Yorkshire |

82 |

-31 |

113 |

5% |

-6% |

9% |

| Zurich |

487 |

-50 |

537 |

69% |

-12% |

186% |

| Urban Areas |

9,061 |

-598 |

9,659 |

22% |

-3% |

42% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| METROPOLITAN AREAS (LABOR MARKETS) |

|

|

|

| Antwerp |

118 |

-42 |

160 |

14% |

-19% |

25% |

| Barcelona |

1,477 |

-207 |

1,684 |

42% |

-11% |

99% |

| Bergamo |

238 |

-11 |

249 |

43% |

-9% |

57% |

| Bologna |

21 |

-117 |

138 |

3% |

-24% |

54% |

| Brussels |

399 |

27 |

372 |

25% |

19% |

26% |

| Copenhagen |

-131 |

-86 |

-45 |

-10% |

-14% |

-6% |

| Florence |

-31 |

-102 |

71 |

-4% |

-22% |

27% |

| Genoa |

-217 |

-246 |

29 |

-24% |

-30% |

34% |

| Lisbon |

952 |

-229 |

1,181 |

51% |

-29% |

108% |

| Madrid |

2,275 |

144 |

2,131 |

63% |

5% |

450% |

| Milan |

24 |

-490 |

514 |

1% |

-28% |

39% |

| Naples |

194 |

-305 |

499 |

10% |

-24% |

66% |

| Palermo |

97 |

5 |

92 |

13% |

1% |

88% |

| Porto |

347 |

-88 |

435 |

37% |

-27% |

71% |

| Rome |

449 |

-39 |

488 |

14% |

-1% |

95% |

| Turin |

-33 |

-270 |

237 |

-2% |

-24% |

37% |

| Metropolitan Areas |

6,181 |

-2,056 |

8,237 |

23% |

-13% |

75% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

15,242 |

-2,654 |

17,896 |

22% |

-8% |

52% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population in 000s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sources: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Urban Area/Metropolitan Area data estimated from UN |

|

|

| Core data from national statistics bureaus |

|

|

|

| Core: Core municipality or previous core municipality where data available |

| Urban Areas/Metropolitan Areas over 750,000 in 1971 or 2001 |

|

| No data for Germany, Austria or Valencia (Spain) |

|

|

|

| Do not report data in urban area or metropolitan area format |

|

| Some cores may have added land area during the period |

|

|

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris and is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Opportunity Urbanism.

Photograph: Paris: Eifel Tower & La Defense from Tour Montparnasse (by author)