You are a political party, and you want to secure the electoral majority. But what happens, as is occurring to the Democrats, when the damned electorate that just won’t live the way—in dense cities and apartments—that you have deemed is best for them?

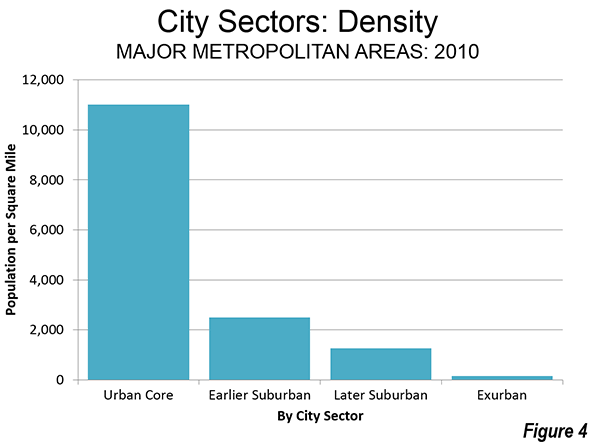

This gap between party ideology and demographic reality has led to a disconnect that not only devastated the Democrats this year, but could hurt them in the decades to come. University of Washington demographer Richard Morrill notes that the vast majority of the 153 million Americans who live in metropolitan areas with populations of more than 500,000 live in the lower-density suburban places Democrats think they should not. Only 60 million live in core cities.

Despite these realities, the Democratic Party under Barack Obama has increasingly allied itself with its relatively small core urban base. Simply put, the party cannot win—certainly not in off-year elections—if it doesn’t score well with suburbanites. Indeed, Democrats, as they retreat to their coastal redoubts, have become ever more aggressively anti-suburban, particularly in deep blue states such as California. “To minimize sprawl” has become a bedrock catchphrase of the core political ideology.

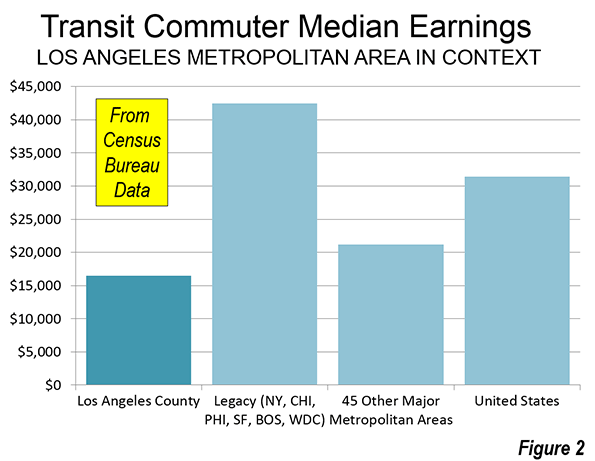

As will become even more obvious in the lame duck years, the political obsessions of the Obama Democrats largely mirror those of the cities: climate change, gay marriage, feminism, amnesty for the undocumented, and racial redress. These may sometimes be worthy causes, but they don’t address basic issues that effect suburbanites, such as stagnant middle class wages, poor roads, high housing prices, or underperforming schools. None of these concerns elicit much passion among the party’s true believers.

The miscalculation is deep-rooted, and has already cost the Democrats numerous House and Senate seats and at least two governorships. Nationwide, in areas as disparate as east Texas and Maine or Colorado and Maryland, suburban voters deserted the Democrats in droves. The Democrats held on mostly to those peripheral areas that are very wealthy—such as Marin County, California or some D.C. suburban counties—or have large minority populations, particularly African-American.

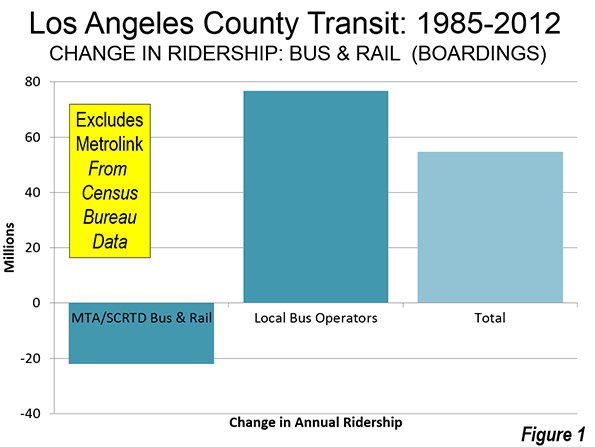

This is not surprising since the policies and predilections of President Obama and his team are based on a largely exaggerated urban mythology. Former HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan, for example, has declared the move to the suburbs is “over.” People are, he has claimed, “moving back into central cities and inner ring suburbs.” To help foster this trend, administration policies at HUD and other agencies have been designed to fulfill Donahue’s vision of getting Americans out of their suburban homes and cars and into apartments and trains. These policy initiatives include large “smart city” grants for dense development, restrictions on new building, the promotion of high-speed rail links that would supposedly reconcentrate economic activity in the urban core. The administration’s strong support for regional governments, and its attempts to force suburbs to diversify their populations (even though they are already where minorities increasingly move) are thinly disguised efforts to promote densification and put the squeeze on suburban growth.

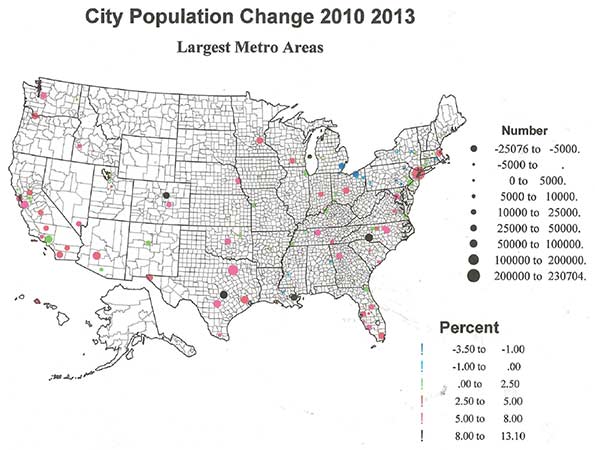

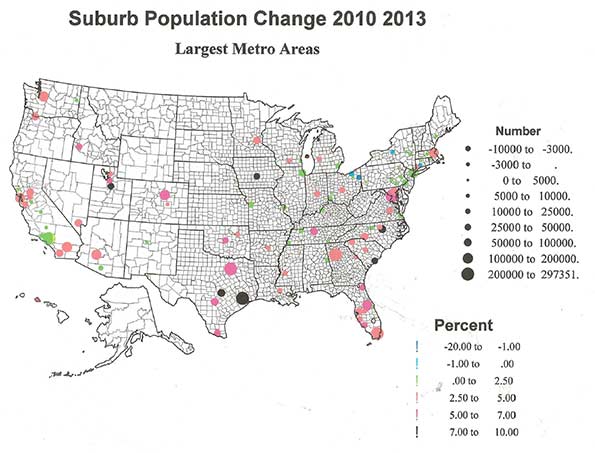

Yet, as census data and electoral returns demonstrate, the demographic realities are nothing like what Donahue and the administration insist. The last decennial census showed, if anything, that suburban growth accounted for something close to 90 percent of all metropolitan population increases, a number considerably higher than in the ’90s. Although core cities (urban areas within two miles of downtown) did gain more than 250,000 net residents during the first decade of the new century, surrounding inner ring suburbs actually lost 272,000 residents across the country. In contrast, areas 10 to 20 miles away from city hall gained roughly 15 million net residents.

Since 2010, suburban growth has slowed as young people, hampered by a weak economy and tougher mortgage standards, have not been able to buy houses. But while population growth in the same time period has been roughly even between the suburbs and core cities, the suburban population, which is so much larger to start with, has continued to expand at a faster rate . According to demographer Morrill, since 2010 the suburbs have added 4.4 million people compared to fewer than 2 million in core cities.

The big problem here is this: the progressives’ war on suburbia is essentially an assault on the preferences of the middle class. Despite the hopes at HUD, the vast majority of Americans—even in most cities and particularly away from the coasts—actually live in single-family homes in low- to mid-density neighborhoods, and overwhelmingly commute by car. If we measure people by how they actually live, notes demographer Wendell Cox, more than 80 percent of those in metropolitan areas have what most would consider a suburban life style.

Contrary to the conventional wisdom, there is nothing intrinsically “progressive” about hating suburbs. It was, after all, President Franklin Roosevelt who believed that dispersion and homeownership would make the country much stronger. “A nation of homeowners, of people who own a real share in their land, is unconquerable,” he maintained. This notion of favoring policies that allowed for middle-class and eventually working-class people to own their own homes and a patch of grass was shared by Harry Truman, John Kennedy, and Bill Clinton, all of whom were fairly successful in winning over suburban voters.

Suburbanites are not intrinsically Republican. Clinton, noted political analyst Bill Schneider, shared suburban voters’ skeptical view of government’s ability to address problems, and won 47 percent of the suburban vote in 1996. Barack Obama, running as a conciliatory pragmatist in 2008, did even better with some 50 percent. This performance was aided by the growing proportion of racial minorities, including African Americans, who had moved to the suburbs.

But as Obama’s administration took shape, suburban support began to ebb. In 2012, Obama lost the suburbs to Romney by a two-point margin. In this year’scongressional elections the GOP edge grew to 12 points in the suburbs, which accounted for a majority of the electorate. The Democrats won by 14 percent in the more urban areas, but these accounted for barely one-third of the total vote. The result was a thorough shellacking of the Democratic party from top to bottom.

Yet even these numbers do not express how critical suburban voters were this year. Much of urban America, particularly in places like Phoenix, Houston, and Las Vegas, is primarily suburban. They have multiple employment centers and the vast majority of commuters take to the roads. Democrats did not do so well in these cities this year, although the party continues to dominate more traditional inner cities dominated by apartment dwellers and mass transit riders. Some hopeful conservative commentators have noted a slight increase in GOP votes in some inner cities, but the percentages are still laughably pathetic.

This can be seen in GOP wins in the governor’s races. Michigan’s Republican Governor Rick Snyder got 6.8 percent of the vote in Detroit. Successful Illinois challenger Bruce Rauner won only 20 percent of Chicago’s take, even in the face of gross mismanagement by his Democratic opponent. And Maryland’s Larry Hogan won about 22 percent in Baltimore. In all these elections, it was the suburbs—not paltry gains in the cities—that made the difference. Rauner’s election, for example, was based largely on a 60 percent margin in Chicago’s swing “collar counties.” Boston’s suburbs, particularly in the more working class south, helped assure the gubernatorial election of GOP candidate Charles Baker in this bluest of blue states. Suburban voters also played a huge role in the Republicans’ biggest win—the Texas governorship—giving GOP candidate Greg Abbott almost two-thirds of their votes.

Much the same suburban swing can be seen in the critical senatorial races races where the Democrats lost seats. Iowa Republican Joni Ernst lost the city vote but won 58 percent of suburban electorate, almost equaling her show in the rural areas. In Colorado, Corey Gardner also secured a large majority among suburban voters, who accounted for roughly half the total electorate. Finally, in the upset of Senator Kay Hagan in North Carolina, successful GOP candidate Thom Tillis ran even better in the suburbs—with some 57 percent of the vote—than he did in the supposedly hardcore conservative countryside.

But the best way to see the suburban impact is to look at the House races. Among the 12 seats that Republicans took from the Democrats, half were located in solidly suburban areas. These included districts surrounding such cities as Raleigh, N.C.; Salt Lake City, which elected black Republican Mia Love; Miami, in a predominately Latino area; Las Vegas, in a suburban district that went for Obama in 2012; and eastern Long Island. The powerful shift in suburban voting also appears to have cost the Democrats two seats in the president’s home state—one in the northern suburbs of Chicago and the other in southern Illinois communities adjacent to St. Louis, a district that has been in Democratic hands for three decades.

So what does this mean for 2016 and beyond? To be sure, the key Democratic urban-centric constituencies—millennials, single women, minorities—likely will turn out in bigger numbers in the next election. But ultimately their numbers will be somewhat balanced by rural and small town voters, who will continue to support conservatives overwhelmingly. Ultimately there is only one truly contested piece of political turf in this country—the suburbs—and who wins there takes the whole enchilada.

There are those, even slightly deluded Republicans, who believe the country is becoming “more urban” and that therefore the suburban edge will mean less in the years ahead. Yet since 2011 the most rapid growth in country, as noted by Trulia’s Jed Kolko, continues to be in the suburbs and exurbs. Some urban cores have recovered nicely, but most often the surrounding city areas have continued to see slow or negative growth.

Nor is this trend likely to reverse in the near future. As Millennials head into their thirties, survey data suggests that most are looking for single family houses and most favor suburban locations where increasingly they will be joined by immigrants and minorities. And virtually all the fastest growth urban regions—Houston, Dallas-Ft. Worth, Phoenix, Charlotte—remain largely suburban in form and character, while growth is much slower in the more traditional legacy cities such as San Francisco, New York, or Boston.

None of this suggests that that Republicans can take suburban votes for granted. The suburbs are changing in ways that could help progressives, notably by becoming more heavily minority and Millennial. The preferences of these new arrivals will differ from those of previous suburban generations—particularly their views on immigration, the need for open space and cultural liberalism. That said, how likely is it that these new suburbanites will embrace progressive ideologues who continually diss the very places they have chosen to live?

The progressive “clerisy” and their developer allies may wish to destroy the suburban dream, but they will not be able to stay in office for long with such attitudes. America remains, and likely will remain, a predominately suburban nation for decades to come. This demographic reality means that whoever wins the suburban vote in 2016 and beyond will inherit the political future.

This piece originally appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Suburbs photo by Bigstock.