Much has been written about the supposed preference of millennials to live in hip urban settings where cars are not necessary. Surveys of best cities for millennials invariably feature places like New York, San Francisco, Chicago and Boston, cities that often are also favorites of the authors.

Yet there has been precious little support for such assertions. I asked demographer Wendell Cox to do a precise, up-to-date analysis of where this huge generation born between 1983 and 2003 actually resides. Using Census American Community Survey data, Cox has drawn an intriguing picture of millennial America, one that is often at odds with the conventional wisdom of many of their elders.

The Hidden Millennials

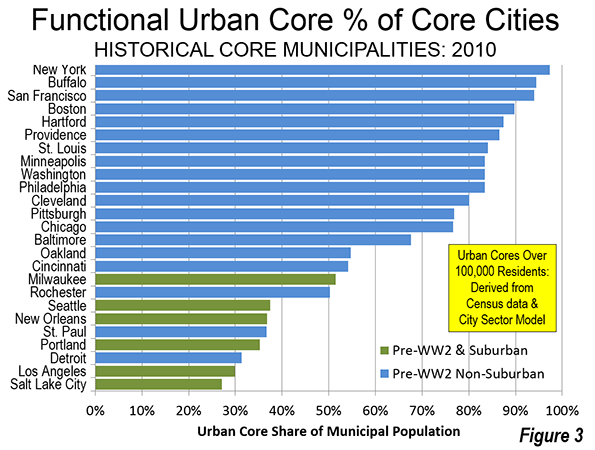

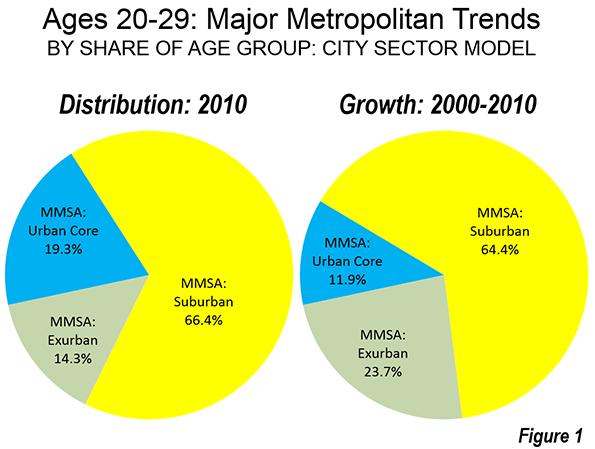

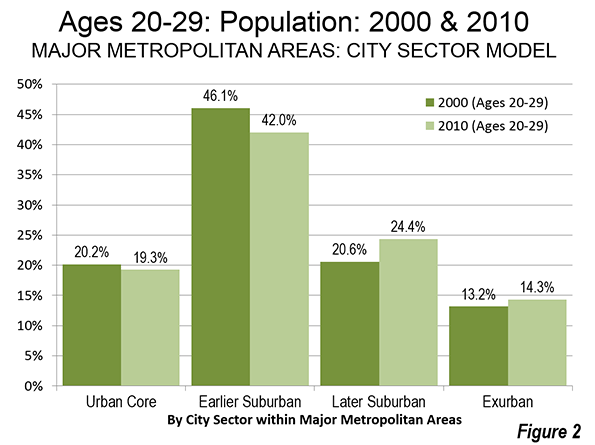

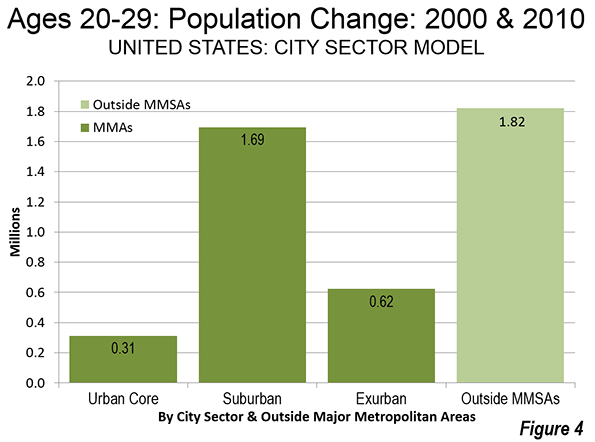

We focused on individuals aged 20 to 29, which represents most of the millennial generation that is finishing post-secondary education and getting established in the workforce. Much of the writing about millennials focuses on their impact on downtowns and urban cores. And to be sure, the numbers of millennials living in urban cores has grown, as downtowns and inner-city neighborhoods have gentrified, particularly in cities such as Boston, Seattle, San Francisco, New York and Chicago. Overall, from 2010 to 2013, the population of 20- to 29-year-olds in core counties (which in most cases are identical to the core city of the metropolitan area) rose by 407,400, or 3.2%.

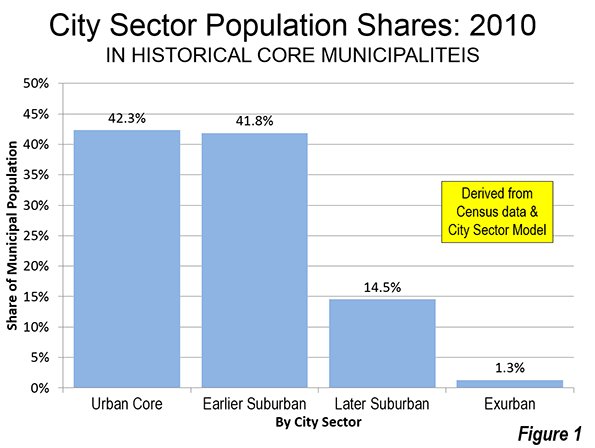

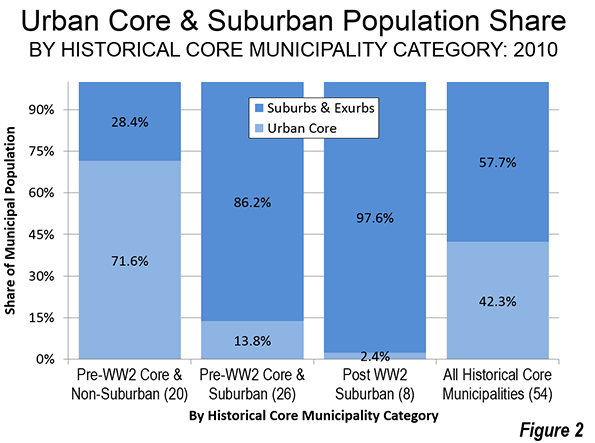

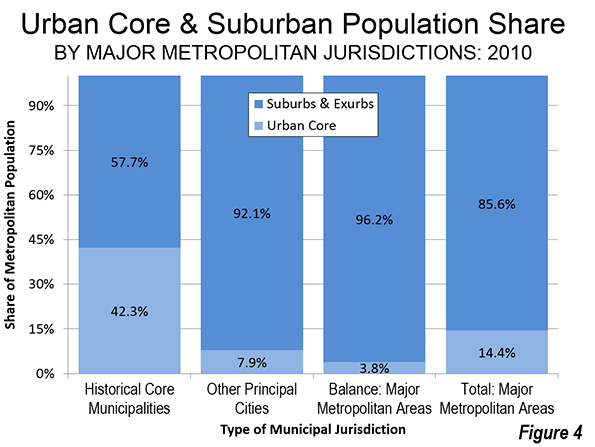

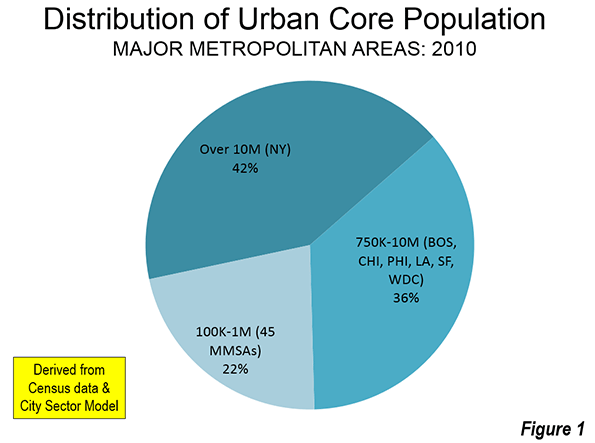

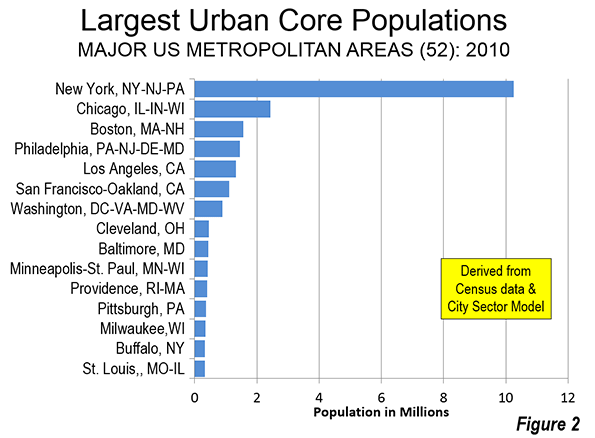

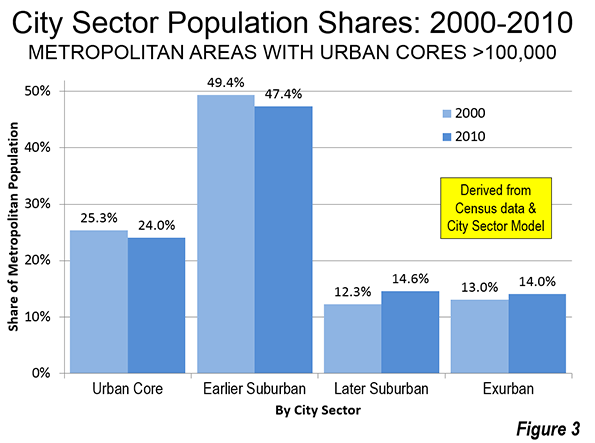

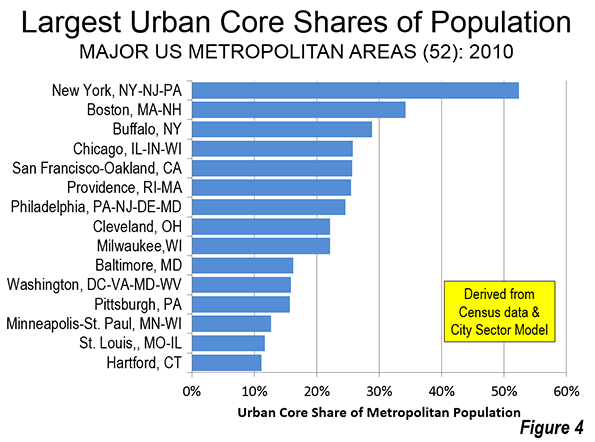

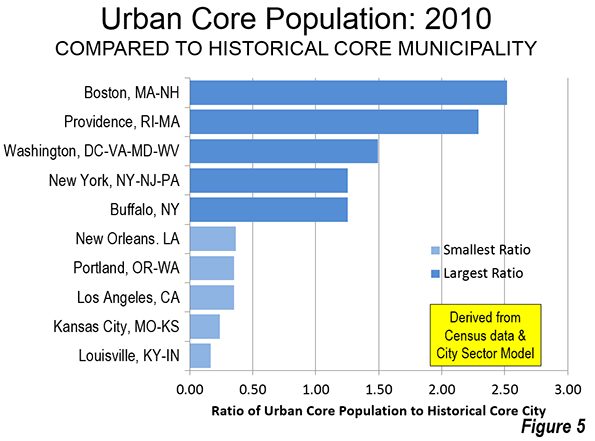

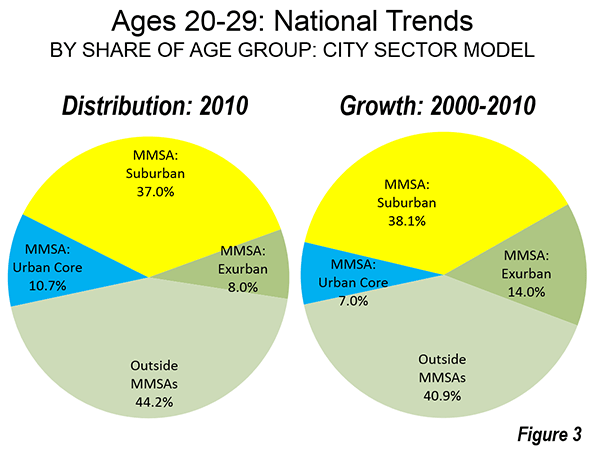

However, that must be put in the context of the overall increase nationwide of that age group in that time span: 4%. Despite the growth in raw numbers of 20- to 29-year-olds living in core counties, the share of the age group living in these areas actually declined slightly, by 0.78%, compared to 2010. Meanwhile, the share of the age group living in the less dense portions of metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas increased. Overall roughly 30% of all millennials live in core counties, which means 70% live somewhere else. In the last three years, the number of millennials outside core counties increased by 1.28 million. In 2010, the functional urban cores, characterized by higher density and higher reliance on transit, were home to 19% of the 20-29s in major metropolitan areas, down from 20% in 2000.

In contrast to the constantly reported on urban hipsters, the vast majority of this generation, who get precious little attention from the media or marketing gurus, might be best described as “hidden millennials.” We have to assume some of these young people are still living, primarily in suburbia, with their parents; a recent Pew study put the percentage of people 18 to 31 living at home at 36%, up from 32% before the recession, as well as the 34% level registered in 2009.

This constitutes a population of over 20 million and not all are hopeless slackers — the vast majority have at least some college education. But they are also disproportionately unemployed or out of the workforce, and, living in their parents’ homes, they are pretty much ignored by everyone except perhaps their friends and relatives. Other millennials may well be living in suburban apartments, which tend to be somewhat less expensive, and others, perhaps the oldest of the group, have begun to “launch” starting families and buying houses, which would tend to put them in the suburbs and smaller cities as well.

Millennial Boomtowns

Equally surprising are those cities that have seen the largest increases in their millennial population. It is dogma among greens, urban pundits, planners and developers that the under 30 crowd doesn’t like what Grist called “sprawling car dependent cities.” Too bad no one told most millennials. For the most part, looking at America’s largest metro areas (the 52 metropolitan statistical areas with populations over a million) the fastest growth in millennial populations tend to be in the Sun Belt and Intermountain West. Leading the way is, San Antonio, Texas, where the 20 to 29 population grew 9.2% from 2010-13, an increase of 28,600.

Right behind it, also in the Sun Belt, are Riverside-San Bernardino, Calif. (8.3%); Orlando, Fla. (8.1%); and Miami (7.7%).

Surprisingly Detroit, long considered a demographic basket case, comes in it at No. 5 in our study, with an impressive 6.8% increase. Given the implosion in the population in the city of Detroit, this growth is likely to have taken place almost entirely in the region’s suburbs, which have done far better both economically and demographically than the core.

The Hipster Capitals Lag

For the most part the “capitals of cool” allegedly so irresistible to millennials rank further down the list. The only two arguable hipster magnets to make the top ten were the Denver metro area (seventh) and Seattle (ninth). The New York metro area ranks 39th with a 3.2% increase, lagging the national expansion in this age group of 4%. The San Francisco-Oakland region, despite the tech boom, places 37th, while the Portland area, renowned as a place where millennials supposedly “go to retire,” ranks 44th. The Chicago metro area’s 20-29 population was essentially unchanged, putting it 49th on our list.

One reason may be that core urban areas are not experiencing the surge in millennials widely asserted. Indeed the millennial populations of the five core counties (or boroughs) of New York grew only 2%, half the national rate of increase and below that of the metro area as a whole.

The same pattern can be seen in the cores of such attractive hipster magnets as San Francisco and Boston, both of which have seen negligible growth among millennials. It appears these areas always attract young people, but also lose them over time. Even more shocking, the 20-29 populations have actually declined since 2010 in the core areas of such much celebrated youth magnets as Chicago (-0.6%) and Portland(-2.5%). Besides Seattle and Denver, the only hip core city showing expanding appeal to millennials is the anomaly of resurgent New Orleans, where the ranks of 20-29 old has grown over 5% since 2010.

The Future of Millennial America

What emerges from this survey is a picture of a millennial America that does not much mirror the one suggested in most media and pundit accounts. The metro areas with the highest percentages of millennials tend, for the most part, to be not dense big cities but either college towns — Austin, Texas; Columbus, Ohio, for example — or Sun Belt cities. Virginia Beach leads the pack, with 17% of its population aged 20 to 29, compared to 14% nationwide.

But overall the towns with the biggest share of millennials today are also those growing this population the fastest: Southern or Intermountain West cities. One big contributing factor is their large Hispanic communities, which for the last three decades have had a far higher birthrate than whites. Latinos constitute 20% of all millennials. This may help explain the large presence of millennials in places like Orlando, Riverside-San Bernardino, and Los Angeles. Other factors may be places where there tend to be high numbers of children, such as Mormon-dominated Salt Lake City.

What these results suggest is that marketers, homebuilders and politicians seeking to target the increasingly important millennial population need to look beyond urban cores. The vast majority of millennials do not live in dense inner city neighborhoods — in fact less than 12% of the nation’s 20-29s did in 2010. Rather than white hipsters, many millennials are working class and minority; in 2012, Hispanics and African-Americans represented 34% of the 20-29 population. Presumably many of them are more concerned with making a living than looking out for “fair trade” coffee or urban authenticity.

Like most of America, the millennials are far more suburban, more dispersed and less privileged than what one sees on shows such as “Girls” or read about in accounts in theNew York Times and the Wall Street Journal. Reality is often more complex, and less immediately compelling, than the preferred media narrative. But understanding the actual geography of this generation may provide a first step to gaining wisdom how to approach and understand this critically important generation.

| 20-29 Population Change: Major Metropolitan Areas: 2010-2013 | ||||

| Rank | Major Metropolitan Area (MMSA) | 2010 | 2013 | Change |

| 1 | San Antonio, TX | 311 | 340 | 9.2% |

| 2 | Riverside-San Bernardino, CA | 605 | 655 | 8.3% |

| 3 | Orlando, FL | 322 | 348 | 8.1% |

| 4 | Miami, FL | 716 | 771 | 7.7% |

| 5 | Detroit, MI | 506 | 541 | 6.8% |

| 6 | Houston, TX | 856 | 909 | 6.2% |

| 7 | Denver, CO | 357 | 378 | 6.0% |

| 8 | Charlotte, NC-SC | 288 | 304 | 5.8% |

| 9 | Seattle, WA | 499 | 528 | 5.7% |

| 10 | Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC | 274 | 290 | 5.6% |

| 11 | Buffalo, NY | 153 | 162 | 5.4% |

| 12 | Jacksonville, FL | 187 | 197 | 5.3% |

| 13 | Grand Rapids, MI | 141 | 148 | 5.2% |

| 14 | Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL | 341 | 359 | 5.1% |

| 15 | Rochester, NY | 146 | 153 | 4.8% |

| 16 | Dallas-Fort Worth, TX | 911 | 954 | 4.7% |

| 17 | Raleigh, NC | 154 | 161 | 4.7% |

| 18 | Los Angeles, CA | 1,941 | 2,032 | 4.7% |

| 19 | Richmond, VA | 167 | 174 | 4.6% |

| 20 | Nashville, TN | 242 | 253 | 4.6% |

| 21 | Indianapolis. IN | 253 | 264 | 4.5% |

| 22 | Phoenix, AZ | 592 | 618 | 4.3% |

| 23 | Sacramento, CA | 307 | 321 | 4.3% |

| 24 | Cleveland, OH | 242 | 252 | 4.3% |

| 25 | Austin, TX | 295 | 307 | 4.2% |

| 26 | Boston, MA-NH | 663 | 690 | 4.1% |

| 27 | Memphis, TN-MS-AR | 182 | 189 | 4.1% |

| 28 | Oklahoma City, OK | 195 | 203 | 4.0% |

| 29 | Atlanta, GA | 719 | 747 | 4.0% |

| 30 | Hartford, CT | 154 | 160 | 3.9% |

| 31 | San Jose, CA | 254 | 263 | 3.9% |

| 32 | Pittsburgh, PA | 293 | 305 | 3.8% |

| 33 | Providence, RI-MA | 217 | 224 | 3.6% |

| 34 | San Diego, CA | 521 | 540 | 3.5% |

| 35 | Baltimore, MD | 381 | 394 | 3.5% |

| 36 | Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV | 818 | 846 | 3.4% |

| 37 | San Francisco-Oakland, CA | 605 | 625 | 3.4% |

| 38 | New Orleans. LA | 176 | 181 | 3.3% |

| 39 | New York, NY-NJ-PA | 2,740 | 2,828 | 3.2% |

| 40 | Columbus, OH | 283 | 291 | 3.0% |

| 41 | Louisville, KY-IN | 159 | 164 | 3.0% |

| 42 | Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD | 823 | 848 | 3.0% |

| 43 | Las Vegas, NV | 277 | 285 | 2.9% |

| 44 | Portland, OR-WA | 306 | 311 | 1.8% |

| 45 | Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN | 280 | 285 | 1.7% |

| 46 | Kansas City, MO-KS | 263 | 267 | 1.3% |

| 47 | St. Louis,, MO-IL | 371 | 372 | 0.2% |

| 48 | Chicago, IL-IN-WI | 1,326 | 1,328 | 0.2% |

| 49 | Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN-WI | 470 | 471 | 0.2% |

| 50 | Birmingham, AL | 151 | 151 | -0.4% |

| 51 | Milwaukee,WI | 216 | 215 | -0.4% |

| 52 | Salt Lake City, UT | 178 | 177 | -0.5% |

| MMSAs | 23,827 | 24,780 | 4.0% | |

| Outside MMSAs | 18,862 | 19,595 | 3.9% | |

| United States | 42,688 | 44,376 | 4.0% | |

| In thousands | ||||

Analysis by Wendell Cox.

This story originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.