As in other major metropolitan areas in the United States, Nashville public officials are concerned about traffic congestion and the time it takes to get around. There is good reason for this, given the research that demonstrates the strong association between improved economic productivity and shorter travel times to work. As Prudhomme and Lee at the University of Paris and Hartgen and Fields at the University of North Carolina Charlotte have shown, metropolitan areas tend to produce more jobs where employees are able to access a larger share of the jobs in 30 minutes.

Ahead in Identifying the Problem: Moreover, Nashville officials are somewhat "ahead of the curve," since traffic congestion is far less severe there than in many other metropolitan areas. Among the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the United States, Nashville ranks 39th in the intensity of its traffic congestion, according to data compiled by INRIX, a traffic information firm. Nashville’s traffic congestion is even better compared to large Western European metropolitan areas .

This favorable traffic situation is despite the fact that Nashville has among the lowest overall transit market shares in the United States or Western Europe (less than 0.5 percent of travel in the metropolitan area). The key to this success, like that of other American metropolitan areas in relation to their international peers is low density and decentralization of employment and other commercial locations.

Missing the Point on Solutions: Yet, it is clear from an editorial in the Nashville Ledger that officials are inclined to embark on an expensive program of transit expansion. Judging from past experience, this offers virtually no hope for reducing traffic congestion or for improving economic productivity in the Nashville metropolitan area.

There are significant misperceptions among local officials about the potential outcomes of proposed commuter rail and bus rapid transit lanes. Perhaps the most important is the assumption that commuter rail and bus rapid transit will reduce travel times. In fact, at the national level, commuting by transit takes approximately twice as long as commuting by single occupant automobile, according to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for 2008 to 2010. Rail systems, such as subways (metros) and light rail do little better than transit in general, taking 95% longer than driving alone and two thirds longer than travel by car pools. There is thus virtually no hope that building new transit lines will reduce travel times.

As often happens when costly new transportation programs are proposed, boosters often resort to erroneous information. The Nashville Ledger cites sources that indicate, for example, that suburban Franklin (in Williamson County, to the south of the Nashville-Davidson County core) has one of the longest work trip travel times in the nation. The reality is quite different. Franklin has an average work trip travel time (23.2 minutes), which is less than national average (25.3 minutes) and little more than Nashville-Davidson County (23.0 minutes).

Nashville officials need look no further than their own eastern suburbs for evidence of the inability of new rail systems to reduce work trip travel times. In 2006, Nashville began commuter rail service from Lebanon, in Wilson County to downtown Nashville (the Music City Star). Currently, the Music City Star is locked in an intensive (and successful, according to the latest data) competition for last place in the number of riders among the nation’s commuter rail systems, just edging out Austin’s new lightly used system. Despite being the only first ring county with commuter rail service, Wilson County work trip travel times are longer than in the other first ring counties. Door-to-door travel times, which are the only travel times that count, have not been reduced by the rail line.

Transit is About Downtown: Transit cannot be a comprehensive metropolitan transportation solution remotely competitive with automobile travel times, except to downtown. This is because the quicker, direct transit services from throughout the metropolitan area that are necessary to attract automobile drivers must focus on the most dense and largest employment center, which is downtown. The radial routes that may be capable of serving downtown effectively simply cannot be afforded for other areas of employment. Our research has indicated, the annual cost to provide automobile competitive transit service throughout an urban area in the United States would consume a huge share of the gross domestic product of any such area.

In Nashville, downtown represents little more than 10% of the metropolitan area employment. Moreover, downtown Nashville represents a declining share of private sector employment in the metropolitan area. According to the Census Bureau’s County Business Patterns, the core Nashville ZIP codes that are served by shuttle buses from the commuter rail station lost 11% of their private sector jobs between 2000 and 2009 (latest data available). At the same time, private sector employment grew 4% in the balance of the Nashville metropolitan area (Note 1).

Transit to Suburban Destinations: A Non-Starter: There have been proposals to require new suburban office development to be near transit stops. This would accomplish little, because transit access in areas other than downtown is so sparse. Among major metropolitan areas, nearly 65% of major metropolitan area workers are within walking distance of a transit stop, according to research by the Brookings Institution. But being near a transit stop does not mean that transit provides practical mobility to anything like 65% of jobs. The reality, according to the Brookings Institution data, is that only 6% of jobs in the average metropolitan area of more than 1 million population can be reached by transit by the average resident in 45 minutes, a travel time nearly double that of the average commuter in the Nashville metropolitan area (Note 2). It seems likely that 30 minute transit access for commuters would be as low as 3% at the national level. This demonstrates the so frequently repeated fallacy equating access to a transit stop with usable access to the metropolitan area.

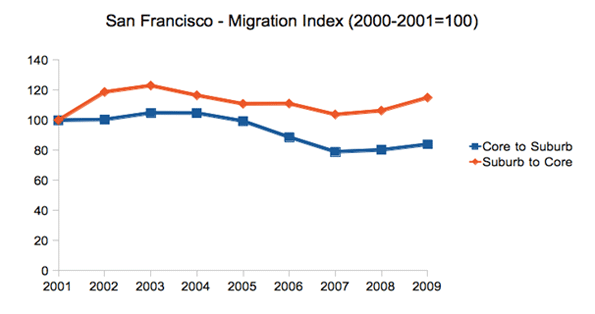

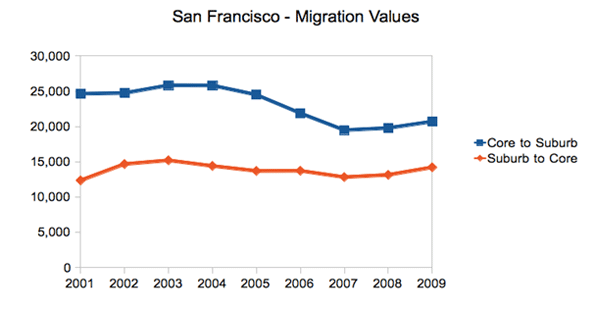

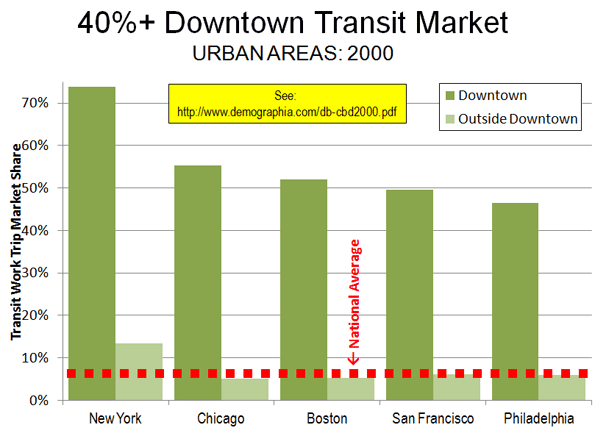

Transit’s Large Downtown Niche Market: There is no question about the effectiveness (though not the cost efficiency) of transit in providing mobility along the most congested corridors to the nation’s largest downtown areas. This transit niche market accounts for nearly 75% of commuting to the Manhattan business core south of 59th Street, and more than 40% to the downtown areas of Brooklyn, Chicago, San Francisco, Boston and Philadelphia. Yet even in these metropolitan areas, where transit mobility is so important to downtown, transit work trip market shares to areas outside downtown are more akin to the national average of 5% (Figure), except in New York.

Of course, Nashville’s downtown is not among these large transit-oriented cores. In 2000, census data indicated that 4% of employees commuted to downtown by transit. Even if all of the ridership on the Music City Star is made up of new downtown transit commuters, that figure would be little changed.

The Need for Stewardship: Before Nashville commits hundreds of millions or billions of tax dollars to expensive transit projects transit in hopes of reducing traffic congestion or travel times, local officials should consider reality. Reducing traffic congestion and travel times are objectives generally beyond transit’s capability. Further, new lines can attract only a small share of commuters, because such a small share of jobs are downtown.

—-

Note 1: County Business Patterns provides employment information that largely excludes government employment. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, 53 percent of metropolitan Nashville’s increase in employment was government jobs between 2000 and 2009.

Note 2: Calculated from Brookings Institution data.

Photograph: Downtown Nashville from BigStockPhoto.com

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”