Is the new American house, with three-car garages and laundry chutes like Olympic ski runs, an improvement over the old ones that were limited to a cozy dining room, a den, and a kitchen that held a small round table on which was kept a toaster?

The size of the American house tracks the evolution of the budget deficit and national debt. Think of McMansions as you would the Federal Reserve Bank—an imposing edifice with the contents of the garage pledged to Household Finance, if not the Chinese.

Many neighborhoods have become the United States of Gatsby.

Because I live in Europe but travel across America to visit family and friends, I will start my appraisal in the guest room.

In my wanderings, I have slept on bunk beds, fold-out sofas (one called “the rack of pain”), camping mats oozing air, and luxury, king-sized mattresses, suitable for a sultan. This summer, I woke up in the middle of the night to find two dogs nestled against my feet. My only objection was when they chose to growl at each other at 3:00 a.m.

What makes a great guest room? My tastes are idiosyncratic, but I like a room that has bookshelves, a good reading light, a clock that works, a large desk, Wi-Fi, windows that open onto cool air, the distant sounds of trains in the night, hooks instead of closet hangers, and a cat that buys into guests.

Instead of television, I prefer a radio beamed up to the BBC World Service and a side table of magazines (ones devoted to gardens, yachts, and celebrity divorces are the best) that I would never buy or read, unless I were a guest. I like coming down in the morning with up-to-date information on Jody Foster’s career. (She’s loyal to Mel Gibson, despite his crazy rants.)

Having been recently in Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and New Jersey, I can report that the American guest room is alive and well. As for the rest of the new American home, the jury is out, or least meeting with the architect to design several thousand more square feet of pool rooms, wet bars, conversation pits, walk-in closets, and fireplaces that ignite with jet propulsion.

When I last lived in the United States in the 1990s, our kitchen was the size of a pantry. If I held my arms outstretched, I could almost touch both walls, and the length was less than that of a stretch limo (literally and figuratively, imagine the oven in the trunk).

Nevertheless, that kitchen was a perfect place to feed a family of four, prepare a dinner party, and hold a conversation. The cost to renovate the kitchen was about $900, but that’s because we went with a “custom” linoleum countertop that fit around the stove top. The overhead light came from a closed New York City school. A neighbor, whose services we won at a charity auction, repainted the cupboards.

Now the American kitchen is the size of Polynesia and comes with archipelagos of “islands,” a nearby “family room,” television screens that could track a lunar launch, machines that dispense coffee and boiling water on demand, hidden drawers that contain freezers, enough marble to impress the Emperor Aurelian, and appliances that give the room the air of an operating theater.

The “new” kitchen is designed to celebrate the diversity of American families—imagine Thanksgiving with the Brady Bunch, maybe over at Bill Cosby’s house—although best as I can judge from my travels, these tribal nations rarely eat together, in the kitchen or anywhere else.

Like nomads, children and adults wander through the new American kitchen as if it were the Serengeti, collecting food and drink until the grazing land is stripped, and then they head off to a cave, to surf the web, text, or watch movies.

I would say that the herd goes to the living room, but I haven’t seen anyone in an American living room since “Gunsmoke” was aired during the Eisenhower administration.

Part of the reason that living rooms are now as forlorn as a safe house is because the television is elsewhere and because there are few formal occasions to sit in the American living room, which often looks as though it could be hired out to a funeral parlor.

As a guest, I am sometimes granted a living-room audience. As a rule of thumb, however, Americans prefer to talk to their guests when standing up in the kitchen or sitting outside on the porch.

Porches are one of the few areas of the house that modern architecture has improved. Screened porches used to be small and cramped, with patches on the screen where the bugs had drilled holes in the night.

In places like Florida, there are now screened porches that are the size of the backyard; in fact, they are the backyard, and the netting and enclosed jungle trees give the terrace the air of a film location on “Survivor.” But I admire anything that allows me to sit outside, beyond the reach of mosquitoes. I also like the practical evolution of the outdoor kitchen, even though the idea seems better suited to the Roman senate.

Part of the reason that many new American houses lack a central focus (think of the courtyard in a Spanish hacienda or an English fireplace) is because television is the high alter of fleeting attention, and screens pop up in all sorts of diverse places, as though part of a billboard campaign.

I have seen televisions in the basement, in small dens, in exercise rooms, on kitchen and living room walls, and on small robotic arms that shift the blue haze around the bathroom as if it were yet another jet spray coming out of the shower or Jacuzzi.

Nevertheless, television watching is a solitary endeavor and programs could be beamed into headsets, for all they foster family or community. Its effect on house layout is put up electronic walls that the architects have spent thousands of dollars to remove, in the spirit of open design.

In my experience, happy houses are those that work in spite of their obvious flaws, like all those New York City apartments that used to have a bath tub in the kitchen or farmhouses with large wood stoves just inside the kitchen door.

In the 1970s, I loved visiting a house in Maryland that instead of a front hall had an indoor rock garden. The meals were cooked outdoors on an open flame, but no one left the dinner table before midnight, unless it was to go for beer (kept outdoors).

The house in which I grew up had claw-footed tubs and one shower. Between 1961 and 1994, when my parents lived there, home improvements consisted of cosmetics and painting (sometimes carried out by one Larry W. Jones, who was a family legend for his ability to paint windows shut).

For years, my parents resisted “improving” the kitchen, because the walls had hand-painted fruit trees and it reminded them of a European café. Nor did they touch the wallpaper in the hall, which had similar scenes of the French revolution.

When they sold the house, the new owners, no doubt in counterrevolutionary horror, tore it down and put up a McMansion, although I have a hard time imagining that they were able completely get rid of all the “fraternité” that would have been lodged in the walls.

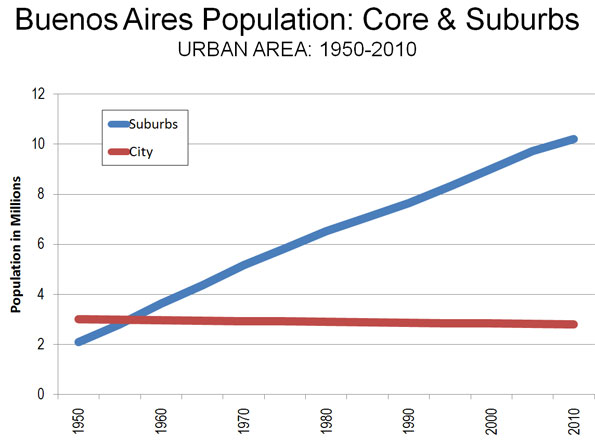

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.