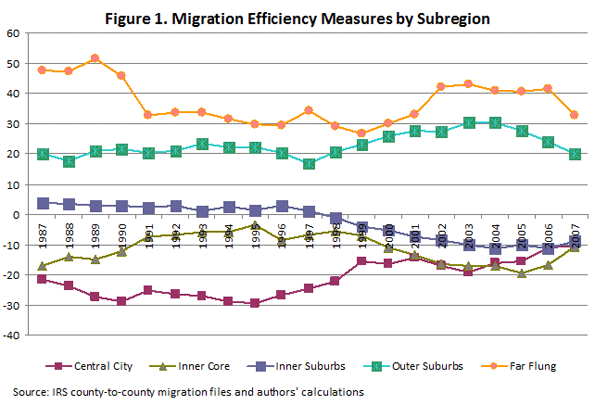

It’s an interesting puzzle. The “cool cities”, the ones that are supposedly doing the best, the ones with the hottest downtowns, the biggest buzz, leading-edge new companies, smart shops, swank restaurants and hip hotels – the ones that are supposed to be magnets for talent – are often among those with the highest levels of net domestic outmigration. New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, Miami and Chicago – all were big losers in the 2000s. Seattle, Denver, and Minneapolis more or less broke even. Portland is the only proverbially cool city with a regional population over two million that gained any significant number of migrants.

Those who find this an occasion for a schadenfreude moment attribute it to tax and regulatory climates. Clearly, things like cost of doing business are clearly very important. And indeed this is often under-rated by cool city proponents. And other things equal, people do prefer low tax jurisdictions. Still, is this the only answer, or is there another explanation? Could it be that rather than high costs driving migration, both costs and migration are being driven by other underlying factors?

Perhaps the root problem is structural change in the economy in the age of globalization. As business became more globalized and more virtualized, this created demand for new types of financial products and producer services – notably in the law, accounting, consultancy, and marketing areas – to help businesses service and control their far flung networks. Unlike many activities, financial and producer services are subject to clustering economics, and have ended up concentrated in a relatively small number of cities around the world.

These so-called “global cities” serve as control nodes for various global networks and key production sites for these services, along with other specialized niches they long had. In effect, more distributed economic activities requires increasing centralization of select functions, particularly the most highly value-added functions. Yet these activities are not set in stone; for example, areas that were once centers for global business, like Cleveland or Detroit, are fading; others like Houston and Dallas are rising.

Yet unlike the Texas cities, which retain a strong middle-class and middle-echelon economy, many of the more elite, established urban centers – for example New York and London – increasingly create parallel economies and labor markets in those cities. These cities now generally contain two kinds of people and firms: those who are part of the global city functions and those who are not. Those who are engaged in global city functions operate in a world of very high value-added activities; specialized, niche skill markets; and rising demand conditions. Those skills are not readily acquired outside of global cities. Often, they are sub-specialized to particular places as different global cities specialize in different niches.

In many cases, these functions have not yet migrated to India or China or often even another global city. This tends to inflate salaries significantly for these specialized, niche skill jobs.

On the other hand, many people who once thrived in these cities have not benefited from these economic forces. They often are in occupations where labor arbitrage is feasible, and their jobs can either be off-shored, or readily transferred to lower cost locales in the US. This includes manufacturing work, but also important but less specialized white collar occupations like basic accounting, loan officers, corporate IT, and HR. In short, the routine side of the traditional monolithic corporate headquarters and services firm.

In effect, in these global cities, two economic geographies share the same physical geography – and those economic geographies are in conflict. One set requires catering to high skill, highly paid workers and firms where cost is a secondary concern. The other involves occupations and industries where cost is very much a concern. The occupants of these two geographies have very different public policy priorities. Which of them will win out?

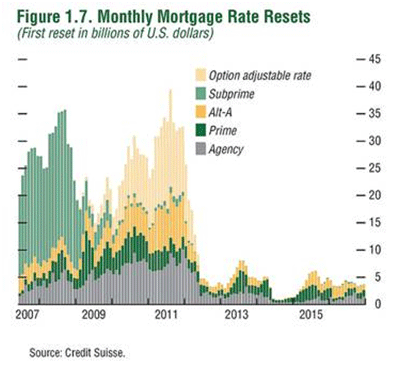

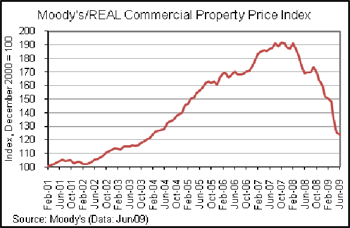

In a global city, particularly a mature and expensive one, the elite geography wins. It is generating the most money, and with money comes power and influence. Additionally, the high wage workers in these industries are simply able to pay more for real estate and other items. Their mere paychecks are driving up costs in the city they live in. They are re-ordering the city in their own high income image, aided and abetted by a speculative financial fueled housing bubble.

The prestige of these industries burnishes the civic brand, making them attractive to civic boosters. What’s more, leaders in global cities feel that these are their businesses of their future. For them the attractiveness of concentrating in areas where you think you can create a “wide moat” advantage makes sense.

This is why cities like Portland, Minneapolis, Denver, and Seattle haven’t fared nearly so badly – they aren’t really full metal global cities and thus, while not always cheap, have remained relatively affordable versus places like San Francisco and New York.

At the same time it is not easy for these more expensive cities to adopt a low tax, low cost approach. For many reasons, places like San Francisco, New York, and London will never, no matter what they do, be able to match Atlanta, Houston, or Dallas, or even Chicago in a war on costs. That would be a suicide mission. Their logical strategy is to follow the law of comparative advantage, and specialize where you have the best competitive position in the market, and that’s global city functions.

Many other cities have followed this strategy, but with differing success. Fearing to end up like the next Michigan and Detroit pair, many states and cities have invested heavily to build up urban amenities to cater to the global city firms and their workers: transit systems, showplace public buildings, art and culture events, bike lanes, and beautification. Cost fell by the wayside as a concern, as did investments in priorities of the traditional middle class.

This explains why, for example, not only have taxes gone up, but things like schools and other basic services have declined so badly in places like California. Traditional primary and secondary education is not important to industries where California is betting its future. Silicon Valley, Hollywood, and biotech draw their workers from the best and brightest of the world. They source globally, not locally. Their labor force is largely educated elsewhere. Basic education and investments in poorer neighborhoods has no ROI for those industries. With the decline of high tech manufacturing in Silicon Valley, even previously critical institutions such as community colleges are no longer as needed.

The same goes for growth and sprawl. They are playing a game of quality over quantity. They specialize in elite urban areas and elite suburbs or exurbs. For example, San Francisco also has Marin, Palo Alto and Los Altos Hills. New York has, in addition to Manhattan, Greenwich and northern Westchester. The only thing they need size for is sheer scale in certain urban functions, and they already have it. Growth is unnecessary for them and only brings problems.

It also explains the highly pro-immigration stance of these cities, as a large service class is needed for globalization’s new aristocrats. Immigrants are needed as low cost labor in the burgeoning restaurant and hotel business. In America’s global cities immigrant housekeepers, landscapers, and nannies are common. They may not dress like His Lordship’s butler, but that doesn’t make them any less servants.

Lastly, it explains why we have seen the same polarizing class pattern so consistently despite broad geographic and socio-political differences between places like Los Angeles, Boston, and Chicago, to say nothing of overseas locales like London. A common global phenomenon probably has a common underlying cause.

The traditional middle class, feeling the squeeze, is simply moving to where its own kind is king and its own priorities are catered to. In a battle of conflicting economic geographies, the one with higher value added wins, displacing others in what Jane Jacobs termed the “self-destruction of diversity”. First, an attractive environment draws diverse uses, then one becomes economically dominant and, through superior purchasing power, displaces other uses over time. The story ends when that dominant economic activity exhausts itself – the true danger facing global cities, though fortunately they are generally not dependent on just one small niche. It’s basic comparative advantage.

If you are just an average middle class guy, why live in one of those global cities anyway? Unless you have roots there that you value, take advantage of something you can’t get anywhere else such as by having a passion for world class opera, or are one of globalization’s courtiers – a hanger on like a high end chef, artist, or indie rocker, perhaps – why put up with the high cost and hassles? It makes no sense. You’re better off living in suburban Cincinnati than suburban Chicago.

And frankly, the folks on the global city side prefer it if you leave anyway. Immigrants are unlikely to start trouble, but a middle class facing an economic squeeze and threat to its way of life might raise a ruckus. That won’t happen if enough of them move to Dallas and rob the rest of critical mass and resulting political clout.

Many of those leaving are college educated, especially, when they get older, get married, and start having families. A relatively large number of these people could be replaced by a smaller number of elite bankers, biotech PhDs, and celebrity chefs. In that case, both “narratives” could hold simultaneously. One type of talent moves in, while a greater number of a different kind moves out. As with trade generally, this could even be viewed as a win-win in some regard.

Again, it is easy to blame the costs and public policy. Clearly there is room for improvement in governance such as reigning in out of control civil service pay and pensions in places like California and New York. But what is more pernicious is the rising income gap in America, and the likely outcomes it drives when a city acquires a small elite economic class with incomes that far outstrip the average, and lacks strong economic linkages to the rest of the city other than for personal services. It sets in motion economic logic that undermines the traditional middle class, which then starts leaving, exacerbating the gap.

For years we worried that a large, stable middle class with a permanent, largely minority underclass constituted an unjust order. As it turns out, the alternatives are sometimes worse. Ultimately some American cities have come to take on the cast of their third world brethren, a perhaps somewhat less extreme version of Mexico City or São Paulo, where vast wealth and glitter exist side by side with the favelas.

This explains why America’s global cities often feel more kinship with their international peers than with many of the places in their own country. The global cities, which now enjoy something of a political ascendency, are also sundering the American commonwealth. Taking steps to prevent a further widening of the income gap may be the only way to save these cities’ middle class – and maintain the solidarity of the country.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.