The troubles of Detroit are well-publicized. Its economy is in free fall, people are streaming for the exits, it has the worst racial polarization and city-suburb divide in America, its government is feckless and corrupt (though I should hasten to add that new Mayor Bing seems like a basically good guy and we ought to give him a chance), and its civic boosters, even ones that are extremely knowledgeable, refuse to acknowledge the depth of the problems, instead ginning up stats and anecdotes to prove all is not so bad.

But as with Youngstown, one thing this massive failure has made possible is ability to come up with radical ideas for the city, and potentially to even implement some of them. Places like Flint and Youngstown might be attracting new ideas and moving forward, but it is big cities that inspire the big, audacious dreams. And that is Detroit. Its size, scale, and powerful brand image are attracting not just the region’s but the world’s attention. It may just be that some of the most important urban innovations in 21st century America end up coming not from Portland or New York, but places like Youngstown and, yes, Detroit.

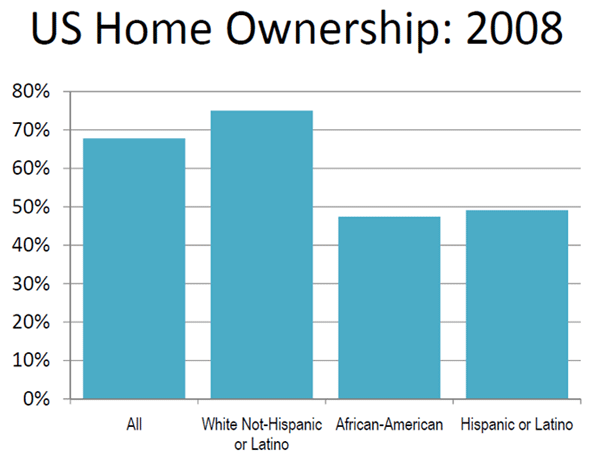

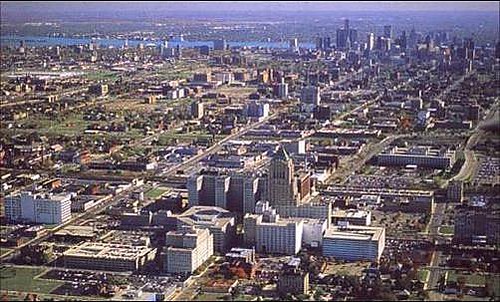

Let’s refresh with this image showing the scale of the challenge in the city of Detroit proper:

There are zillions of pictures to illustrate the vast emptiness in Detroit. Kaid Benfield at NRDC posted these:

This phenomenon prompted someone to coin the term “urban prairie” to capture the idea of vast tracts of formerly urbanized land returning to nature. The folks at Detroit’s best discussion site, DetroitYES, posted this before and after of the St. Cyril neighborhood. Before:

After:

A site named “Sweet Juniper” recently had a fantastic photo of the spontaneous creation of “desire line” paths across all this vacant land. You should click to enlarge this photo.

One natural response is the “shrinking cities” movement. While this has gotten traction in Youngstown and Flint, as well as in places like Germany, it is Detroit that provides the most large scale canvas on which to see this play out, as well as the place where some of the most comprehensive and radical thinking is taking place. For example, the American Institute of Architects produced a study that called for Detroit to shrink back to its urban core and a selection of urban villages, surrounded by greenbelts and banked land. Here’s a picture of their concept:

It seems likely that this will get some form of traction from officialdom, as this article suggests, though implementation is likely to be difficult.

Detroit is also attracting dreams of large scale renewal through agriculture, as Mark Dowie writes in Guernica (hat tip @archizoo).

Were I an aspiring farmer in search of fertile land to buy and plow, I would seriously consider moving to Detroit. There is open land, fertile soil, ample water, willing labor, and a desperate demand for decent food. And there is plenty of community will behind the idea of turning the capital of American industry into an agrarian paradise. In fact, of all the cities in the world, Detroit may be best positioned to become the world’s first one hundred percent food self-sufficient city.

This isn’t just a crazy idea from some guy who lives in California. He documents several examples of people right now, today growing food in Detroit. It wouldn’t surprise me, frankly, if Detroit produces more food inside its borders today than any other traditional American city.

About five hundred small plots have been created by an international organization called Urban Farming, founded by acclaimed songwriter Taja Sevelle. Realizing that Detroit was the most agriculturally promising of the fourteen cities in five countries where Urban Farming now exists, Sevelle moved herself and her organization’s headquarters there last year. Her goal is to triple the amount of land under cultivation in Detroit every year. All food grown by Urban Farming is given free to the poor. According to Urban Farming’s Detroit manager, Michael Travis, that won’t change.

The fact that Urban Farming moved to Detroit is exactly the effect I’m talking about. To anyone with aspirations in this area, it is Detroit that offers the greatest opportunity to make your mark. It is the ultimate blank canvas. For urban agriculture and many other alternative urban dreams, it is Detroit, not New York City that is the ultimate arena in which to prove yourself.

It’s not just farmers; intellectuals and artists of various types are drawn to Detroit, both to study it and pursue ideas about the remaking of the city:

Detroit has achieved something unique. It has become the test case for all sorts of theories on urban decay and all sorts of promising ideas about reviving shrinking cities.

“It’s unbelievable,” said Sue Mosey, president of the University Cultural Center Association, who has been interviewed recently by two separate PBS crews and an Austrian journalist writing about Detroit.

“All of us have been inundated with all of these people who somehow think that because we’re so bottomed out and so weak-market, that this is this incredible opportunity,” Mosey said.

Robin Boyle, a professor of urban planning at Wayne State University who has been interviewed by numerous visitors, echoed that sentiment.

“They realize that there is an interesting story to tell, that has real characters, but even more, they discover a place that is simply not like everywhere else,” he said.

Toby Barlow wrote in the New York Times about out of towners buying up $100 houses, moving to Detroit, and doing all sorts of interesting things with them:

Recently, at a dinner party, a friend mentioned that he’d never seen so many outsiders moving into town…Two other guests that night, a couple in from Chicago, had also just invested in some Detroit real estate. That weekend Jon and Sara Brumit bought a house for $100.

….

A local couple, Mitch Cope and Gina Reichert, started the ball rolling. An artist and an architect, they recently became the proud owners of a one-bedroom house in East Detroit for just $1,900. Buying it wasn’t the craziest idea. The neighborhood is almost, sort of, half-decent. Yes, the occasional crack addict still commutes in from the suburbs but a large, stable Bangladeshi community has also been moving in.So what did $1,900 buy? The run-down bungalow had already been stripped of its appliances and wiring by the city’s voracious scrappers. But for Mitch that only added to its appeal, because he now had the opportunity to renovate it with solar heating, solar electricity and low-cost, high-efficiency appliances.

Buying that first house had a snowball effect. Almost immediately, Mitch and Gina bought two adjacent lots for even less and, with the help of friends and local youngsters, dug in a garden. Then they bought the house next door for $500, reselling it to a pair of local artists for a $50 profit. When they heard about the $100 place down the street, they called their friends Jon and Sarah.

….But the city offers a much greater attraction for artists than $100 houses. Detroit right now is just this vast, enormous canvas where anything imaginable can be accomplished. From Tyree Guyton’s Heidelberg Project (think of a neighborhood covered in shoes and stuffed animals and you’re close) to Matthew Barney’s “Ancient Evenings” project (think Egyptian gods reincarnated as Ford Mustangs and you’re kind of close), local and international artists are already leveraging Detroit’s complex textures and landscapes to their own surreal ends.

In a way, a strange, new American dream can be found here, amid the crumbling, semi-majestic ruins of a half-century’s industrial decline. The good news is that, almost magically, dreamers are already showing up. Mitch and Gina have already been approached by some Germans who want to build a giant two-story-tall beehive. Mitch thinks he knows just the spot for it.

It’s what Jim Russell likes to call “Rust Belt chic”, and Detroit has it in spades.

This piece also highlights the absolutely crucial advantage of Detroit. It’s possible to do things there. In Detroit, the incapacity of the government is actually an advantage in many cases. There’s not much chance a strong city government could really turn the place around, but it could stop the grass roots revival in its tracks.

Can you imagine a two-story beehive in Chicago? In many cities where strong city government still functions effectively, citizens are tied down by an array of regulations and permits that are actually enforced in most cases. Much of the South Side of Chicago has Detroit like characteristics, but the techniques of renewal in Detroit won’t work because they are likely against code and would be shut down the minute someone complained. Just as one quick example, my corner ice cream stand dared to put out a few chairs for patrons to sit on while enjoying a frozen treat on a hot day. The city cited them for not having a license. So they took them away and put up a “bring your own chair” sign. The city then cited them for that too. You can’t do anything in Chicago without a Byzantine array of licenses, permits, and inspections.

In central Indianapolis, which is in desperate need of investment, where the city can’t fill the potholes in the street, etc., the minute a few yuppies buy houses in an area and fix them up, they immediately petition for a historic district, a request that has never been refused, ensuring that anyone who ever wants to do anything will be forced to run a costly and grueling gauntlet of variances, permits, hearings, etc. Only the most determined are willing to put up with that.

In most cities, municipal government can’t stop drug dealing and violence, but it can keep people with creative ideas out. Not in Detroit. In Detroit, if you want to do something, you just go do it. Maybe someone will eventually get around to shutting you down, or maybe not. It’s a sort of anarchy in a good way as well as a bad one. Perhaps that overstates the case. You can’t do anything, but it is certainly easier to make things happen there than in most places because the hand of government weighs less heavily.

What’s more, the fact that government is so weak has provoked some amazing reactions from the people who live there. In Chicago, every day there is some protest at City Hall by a group from some area of the city demanding something. Not in Detroit. The people in Detroit know that they are on their own, and if they want something done they have to do it themselves. Nobody from the city is coming to help them. And they’ve found some very creative ways to deal with the challenges that result. Consider this from the Dowie piece:

About 80 percent of the residents of Detroit buy their food at the one thousand convenience stores, party stores, liquor stores, and gas stations in the city. There is such a dire shortage of protein in the city that Glemie Dean Beasley, a seventy-year-old retired truck driver, is able to augment his Social Security by selling raccoon carcasses (twelve dollars a piece, serves a family of four) from animals he has treed and shot at undisclosed hunting grounds around the city. Pelts are ten dollars each. Pheasants are also abundant in the city and are occasionally harvested for dinner.

This might sound awful, and indeed it is. But it is also an inspiration and a testament to the human spirit and defiant self-reliance of the American people. I grew up in a poor rural area where, while hunting is primarily recreational, there are still many people supplementing their family diet with wild game. Many a freezer is full of deer meat, for example. And of course, rural residents have long gardened, freezing and canning the results to help get them through the winter. So this doesn’t sound quite so strange to me as it might to you. The fate of the urban poor and the rural poor are more similar than is often credited. And contrary to stereotypes the urban poor often display amazing grit and ingenuity, and perform amazing feats to sustain themselves, their families and communities.

As the focus on agriculture and even hunting show, in Detroit people are almost literally hearkening back to the formative days of the Midwest frontier, when pioneer settlers faced horrible conditions, tough odds, and often severe deprivation, but nevertheless built the foundation of the Midwest we know, and the culture that powered the industrial age. No doubt in the 19th century many of those sitting secure in their eastern citadels thought these homesteaders, hustlers, and fortune seekers crazy for leaving the comforts of civilization to head to places like Iowa and Chicago. But some saw the possibilities of what could be and heeded the call to “Go West, young man.” We’ve come full circle.

More Detroit

Detroit: Do the Collapse

Detroit: Not the Future of the American City

For talent – good jobs, cools places, new narrative (Crain’s Detroit Business – featuring Yours Truly)

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.